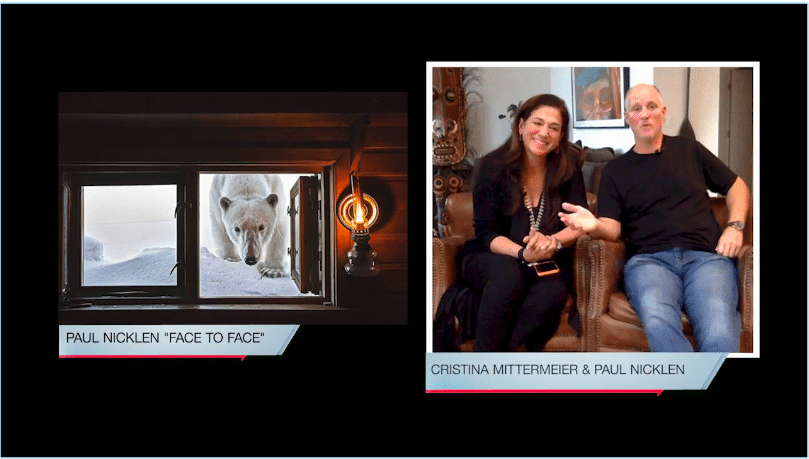

The Modern Eco-Warriors: A Fundraiser for SeaLegacy

The Modern Eco-Warriors: A Fundraiser for SeaLegacy

Video Player

Media error: Format(s) not supported or source(s) not found

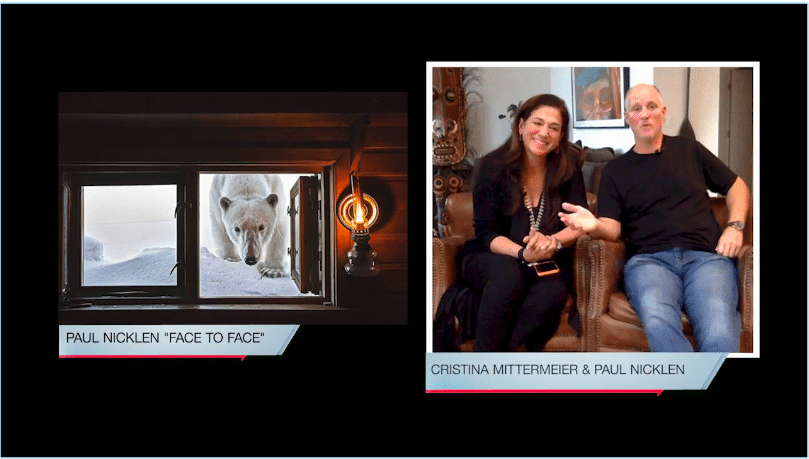

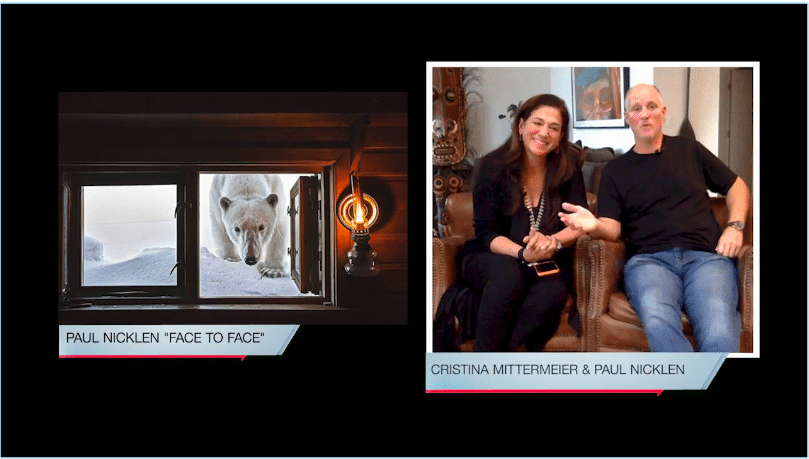

Download File: https://hiltoncontemporary.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/paul_nicklen_face_to_face_hilton_asmus_live-_final_245.mp4?_=1Video Player

Media error: Format(s) not supported or source(s) not found

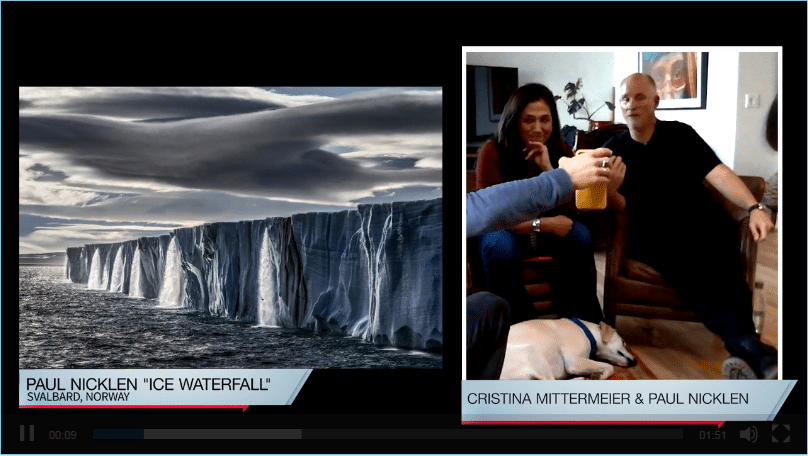

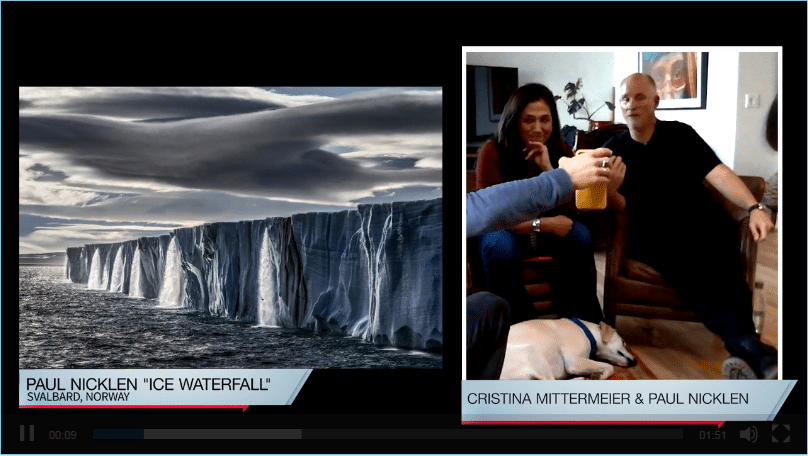

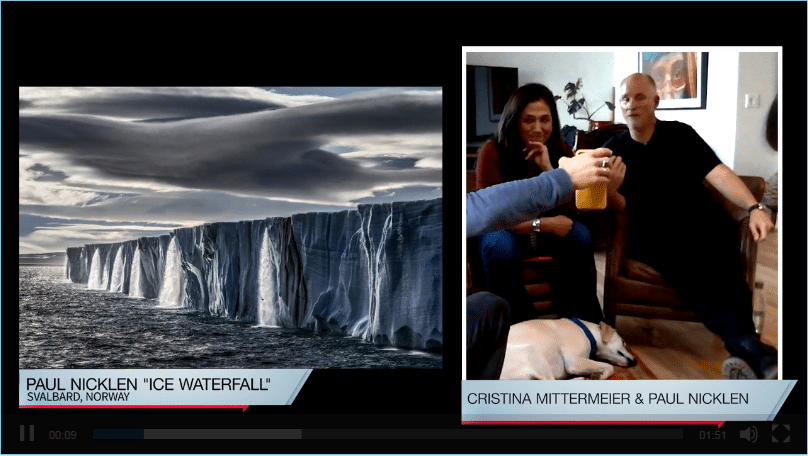

Download File: https://hiltoncontemporary.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/paul_nicklen_ice_waterfall_hilton_asmus_live_-_final_467.mp4?_=2Video Player

Media error: Format(s) not supported or source(s) not found

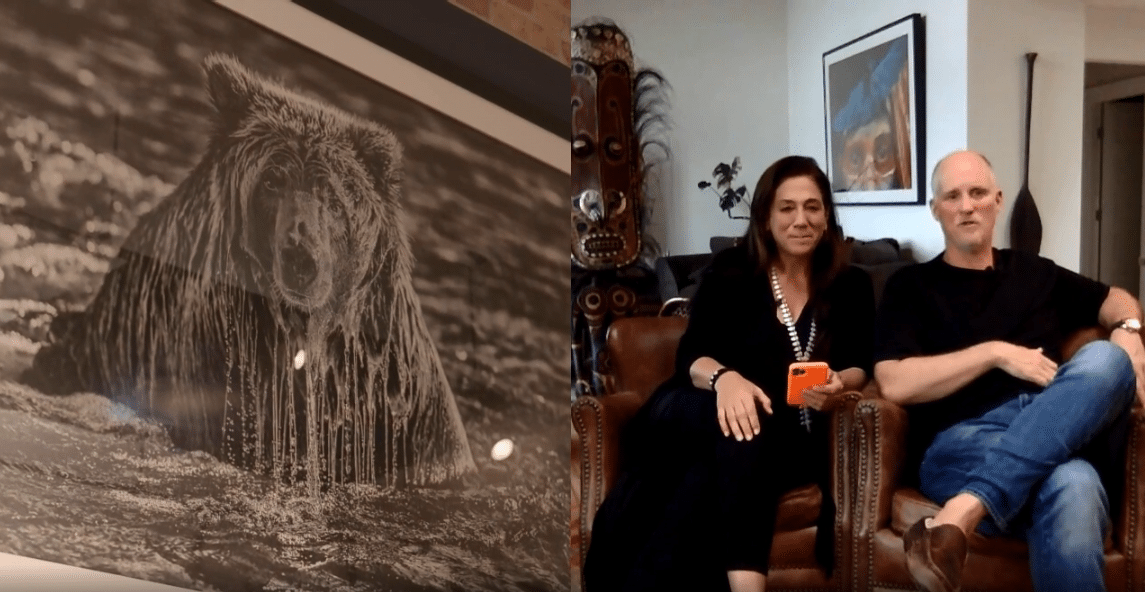

Download File: https://hiltoncontemporary.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/paul_nicklen_talks_aobut_morris_the_bear_776.mp4?_=3