Artists

The Final Step: Turning My Photos Into Prints for Galleries Around the World

BY: MARKUS KLINKO

JAN 05, 2023

Artists

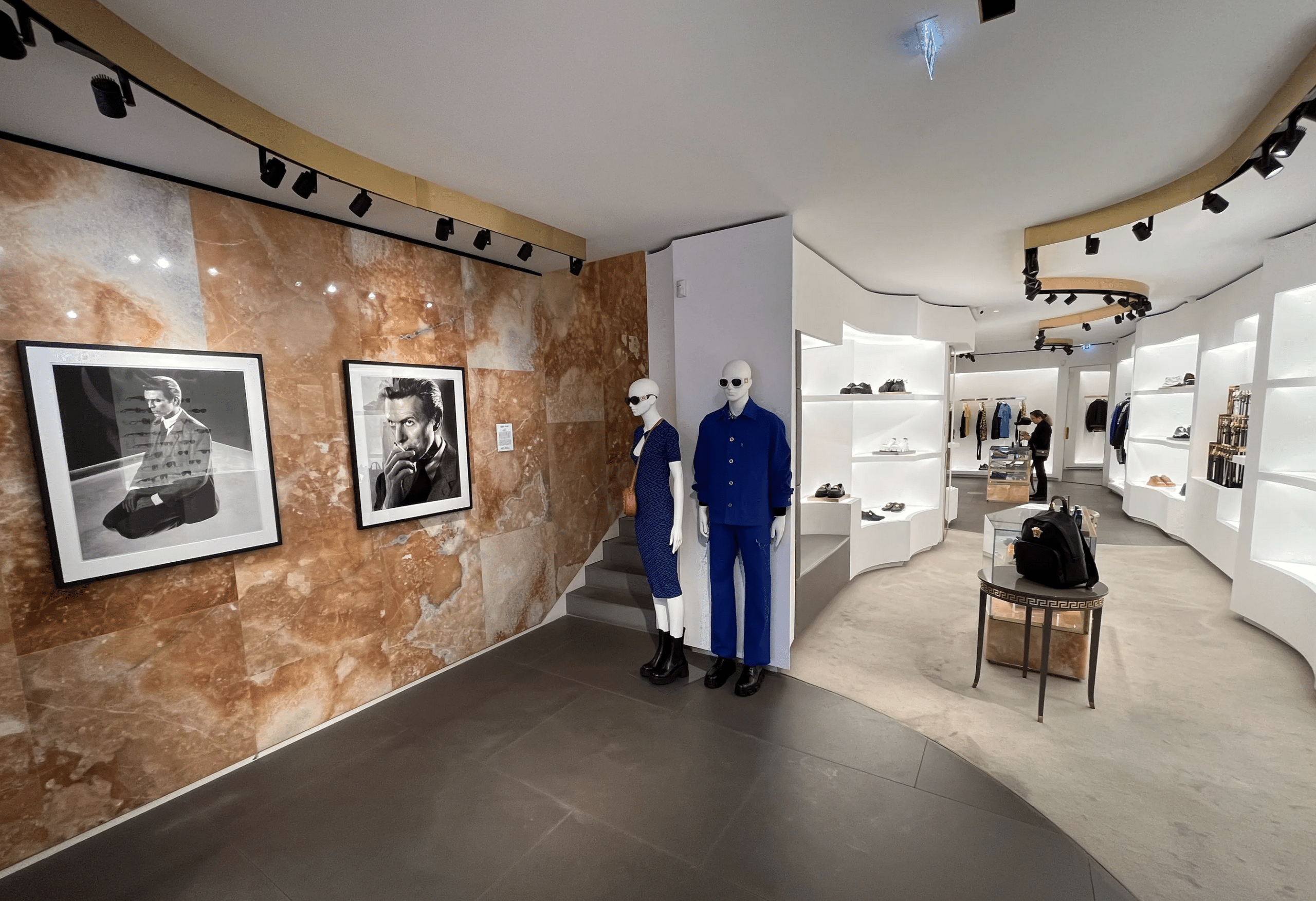

Une trentaine d'œuvres, à la fois physiques et digitales, du photographe américain sont exposées dans la boutique Versace de Bruxelles.

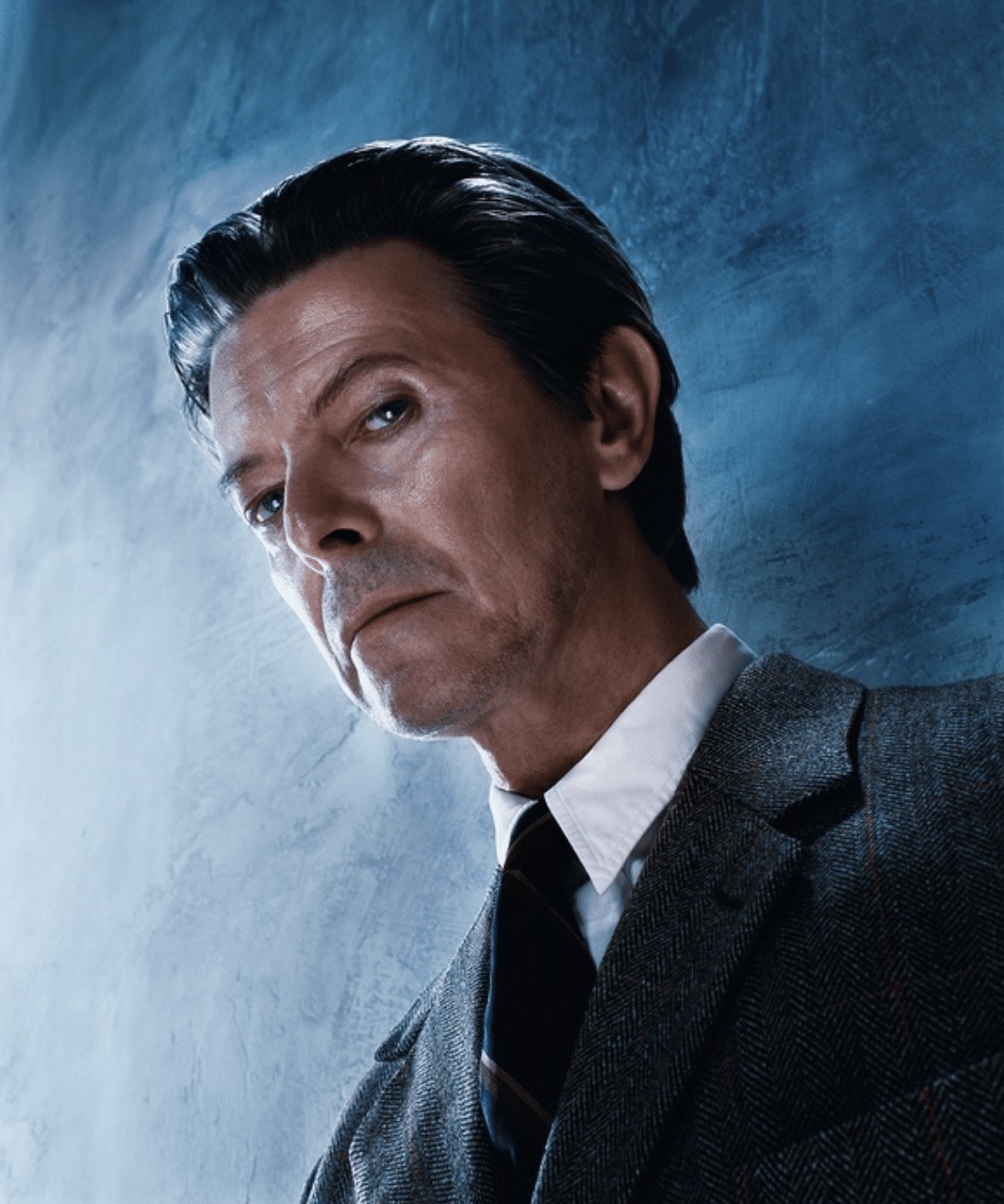

Creating a successful photograph is a process that has numerous stages. Printing the work masterfully, usually the last portion of the endeavor, is paramount.

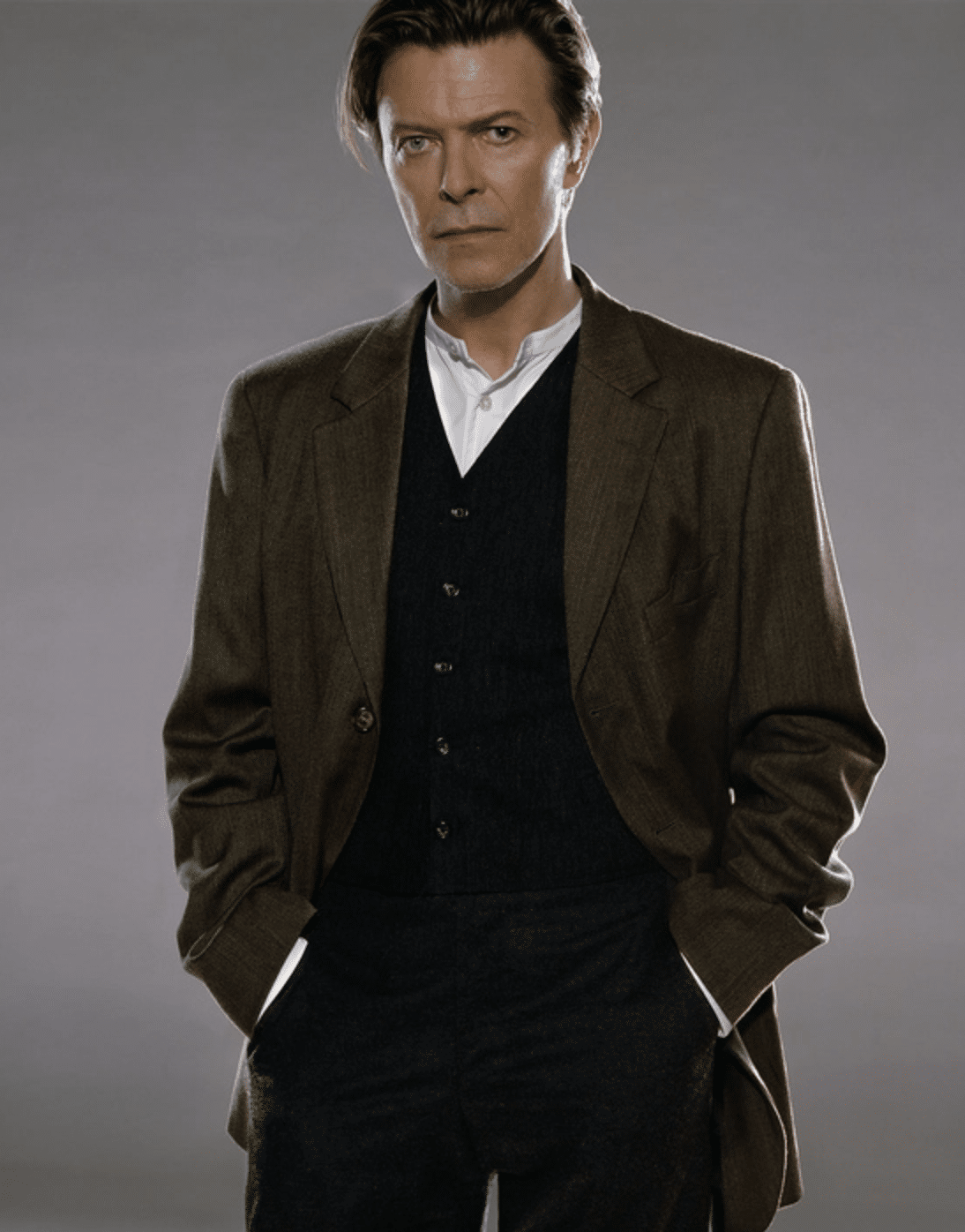

As I enter my 29th year as a documentarian of pop culture (often referred to as fashion/celebrity photographer), I have seen my work move from the covers of magazines onto the walls of art galleries, museums, and private art collections.

Now getting ready for new shows in Houston, Texas, and Ventura, California, it is time to talk about the all-important aspect of printing.

After all, the print is what everyone sees, and what the photograph will be judged by. So why not pay a little tribute to the people that make this all happen?

There are many ways to make a gorgeous print, and choosing the ideal paper is critical. For my work, I prefer a glossy luster, so Fujicolor Crystal Archive Digital Pearl is my paper of choice.

It has a distinct metallic reflection effect that suits my work to perfection. I also love Fujiflex Crystal Archive Printing Material, for its razor-sharp rendering, vibrant colors, and impeccable whites.

I do not print my own work — after many trials and errors, I have had the fortune of collaborating exclusively with the great master printer, John Weldon of LA’s famous Weldon Color Lab. After working with John for many years on dozens of solo exhibitions, group shows, and art fairs, I recently sat down with John for a bit of a recap of his career, and to hear how he applies his talent and great experience to my work.

I asked John about his journey to becoming one of the world’s premier printmakers and how it all started.

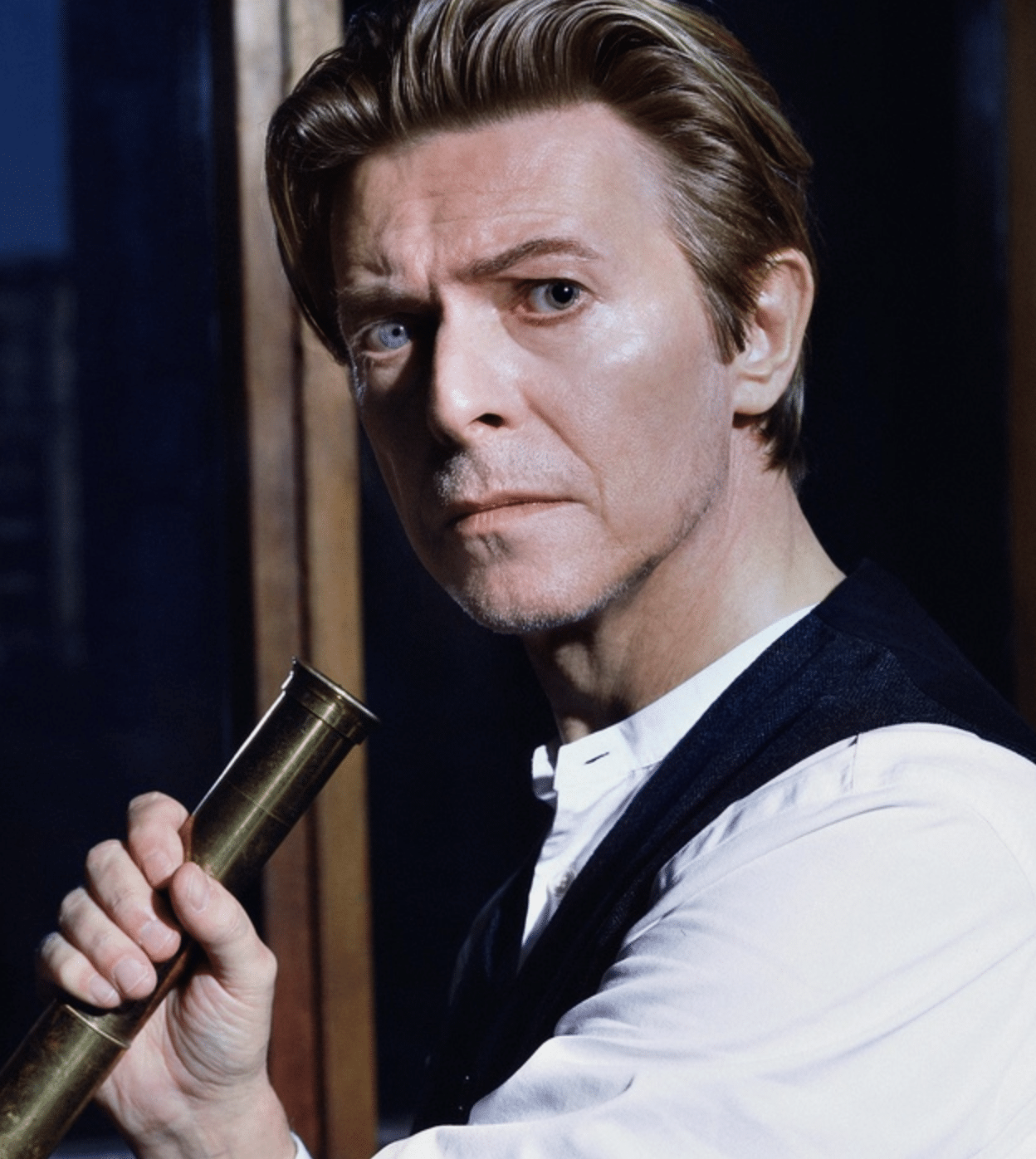

“My freshman year in high school I found an old telescope in the closet and my dad, an engineer on the first Apollo missions, told me I’d be able to see the craters on the moon,” John says. “It was so amazing that I put my camera up to the eyepiece and when I got the film back from the drugstore it came back with a note on it: no charge – no images. So I shot it again and put a note on it that the photos were of stars and planets, and the white dots on the film were the actual photos. The roll came back with another note: no charge – no images.

“My dad saw this and for Christmas gave me an old darkroom set-up so that I could process the photos myself. Next thing you know I started processing color prints in the darkroom I’d built in my bathroom! When I showed some neighbors my photos pretty soon they started bringing me their negatives to print.

“While still in high school by chance I discovered a black and white rental darkroom in the neighborhood, and soon they offered to pay me to do color printing for them. Ten years later, in 1989, my fascination with photography inspired me to open my own photo lab at our current location where I began specializing in Cibachrome printing. As the technology has continued to evolve, so too has the lab continued to grow. We are currently one of the only labs in the world with top expertise in Lightjet printing.”

John says the challenge of helping photographers achieve their vision is the “secret ingredient” behind what allowed his lab to develop its reputation as one of the premier printing companies in North America.

The lab has grown to offer a very wide range of services for photographers.

“We do it all at Weldon – from film development to scanning to printing and mounting!” John says. “Our state-of-the-art Lightjet printing offers an amazing level of vibrancy. And our archival inkjet prints allow for a complete range of unique papers and surfaces to choose from to complement any type of photograph. We develop film in our custom black-and-white film-processing lab with great care by hand, utilizing traditional archival development.

“Our scanning department offers a range of services, including high-resolution drum scanning, and flatbed scanning, and our digital photography can accommodate reproduction of large-scale paintings.”

I asked John whether most of his clients have specific requests regarding the printing process and the paper used, or whether he helps to direct artists to their eventual choices.

“While we do assist clients new to photography every week select the best options for their images, the majority of our clients are professional photographers, museums, and galleries,” John says. “Professionals usually know what kind of style they want, but are always happy to hear about the latest innovations.”

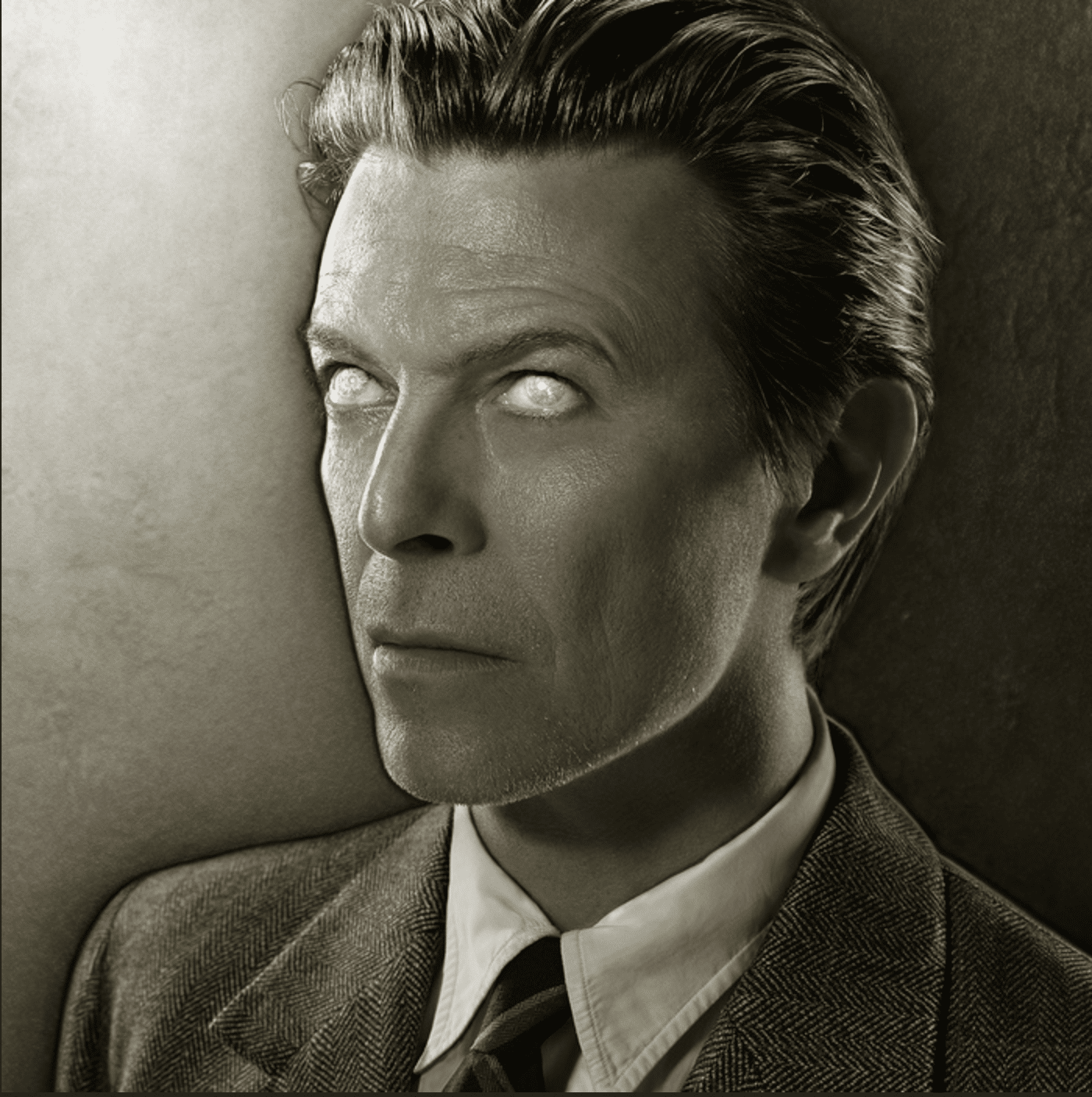

Weldon Color Lab recently introduced the historic art of platinum palladium printing, which inspired me to release my David Bowie Platinum Edition — a platinum print I have included in my STARMAN show.

“Platinum-palladium prints are unrivaled by any modern printing technique, both in appearance and performance,” John says. “One reason the prints, created on Hahnemuhle paper, are favored by art collectors is due to their longevity, achieving an archival rating in excess of 1,500 years. And in terms of appearance, the prints create an added sense of depth, and the tonal range of the prints is unmatched.

“Dating back to the 1870s, this handmade photographic-printmaking technique was created through contact printing, meaning the photographic negative matches the size of the final print. As a result, photographers of the times were more limited to what size they could make their prints. Now we can make ‘digital negatives’ up to 40″ wide! Currently, we are printing up to 24×30″ and are excited that later this year will be able to print 30×40″ platinum-palladium prints.”

John says his lab is currently looking to expand its platinum services to serve galleries and museums around the world.

About the author: Markus Klinko is an international fashion/celebrity photographer who has worked with many of today’s most iconic stars of film, music, and fashion. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can find more of Klinko’s work on his website and Instagram.

Joan Didion Remembers the Day Julian Wasser Took Her Portrait

Artists

Vogue spoke with Joan Didion and Julian Wasser about his portraits of her, now in Wasser’s new monograph, The Way We Were.

BY ABBY AGUIRRE

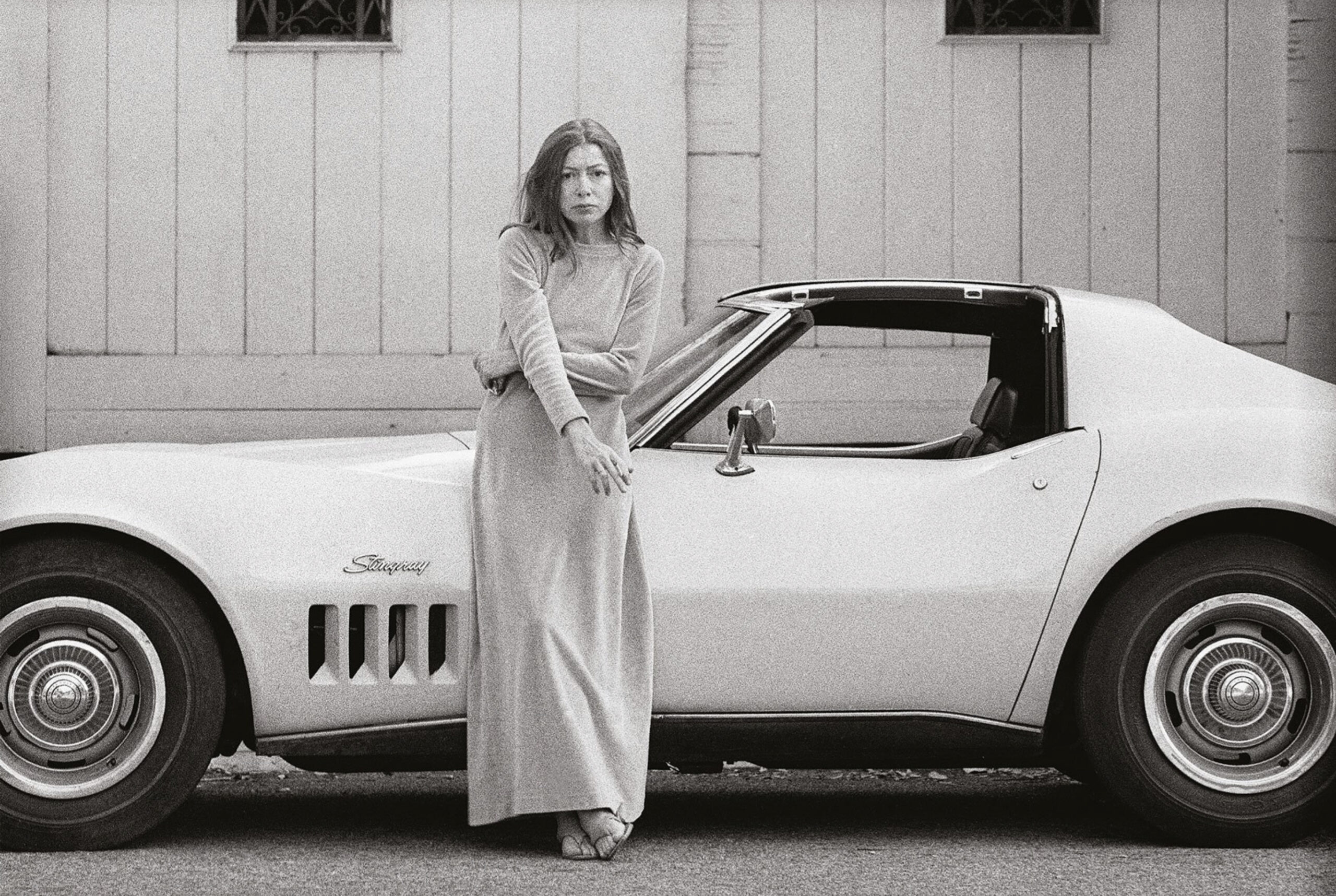

Shortly after Slouching Towards Bethlehem was published, in 1968, Timemagazine commissioned portraits of Joan Didion by the photographer Julian Wasser. You know the series: a young Didion in a long-sleeved dress and sandals, standing in front of her Corvette Stingray, a cigarette dangling from her right hand. Two of these portraits appear in Wasser’s new monograph, The Way We Were, published recently by Damiani, alongside many of his other seminal photographs: Steve McQueen exhaling a cloud of cigarette smoke; Robert F. Kennedy five minutes before he was shot; Roman Polanski kneeling near the entrance of the house on Cielo Drive, the word PIG,scrawled in blood by the Manson family, faded but still visible on the door.

Of all the pictures he took during those years, Wasser says, speaking by phone from Los Angeles, the ones of Didion were “a big event in my life.” “I’d read her fiction,” he says. “It was very L.A. She didn’t miss a thing. She was such a heavyweight person.” Wasser shot Didion on the Strip and at her rented house on Franklin Avenue in Hollywood, where she lived with her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne, and their daughter, Quintana Roo. “It was a very nice, cozy house,” Wasser remembers. “And she was a very easy person to talk to. It was like a dream. Quite nice and relaxed. No Hollywood phoniness.” Vogue asked Didion, too, for her memories of the shoot.

These portraits were commissioned by Time in 1968, just after Slouching Towards Bethlehem was published to great acclaim. What do you remember about this moment in your life?

I think someone said that the picture had been taken under circumstances that it hadn’t. What do I remember? I can’t say what I remember. I had a baby. I was living in a rented house in Hollywood. It was kind of a wonderful period of my life actually. Not because I was in a rented house in Hollywood. But just in general.

As a writer and reporter, was it strange for you to be the subject of a story? To be appearing in Time?

I don’t think it was the first time I’d been written about. The whole thing was strange. Yes, it was strange to be written about. But that probably wasn’t the first time. I loved having pictures of me with the baby. The one where she has sort of—the one that shows her hair pulled up tight? I love that picture. I love that picture. That was also at Franklin Avenue. Most of what Julian Wasser took was at Franklin Avenue.

Was this the first time you met Julian Wasser? Were you familiar with his work?

I was very familiar with his work because I was writing for magazines then and he was at the Time bureau. Any time anyone was shooting in L.A. for Time and Life, they were shooting with Julian. He was just somebody I knew very well.

What details do you remember about that day? Does anything in particular stand out to you now?

I can’t remember anything specific that stands out about the day. I don’t know how we decided to include the Corvette. It must have been some whim of Julian’s.

He said it was not his whim. He said, “You don’t tell a woman like that what to do.”

[Laughs] Oh, really?

Had you thought about what you were going to wear, or were the long dress and sandals just what you happened to have on?

I remember the long dress. I remember being out on the Strip in a long dress. Why, I can’t imagine.

Do you remember buying the Stingray?

I very definitely remember buying the Stingray because it was a crazy thing to do. I bought it in Hollywood.

What color was the Stingray?

The Stingray was Daytona yellow. Which was a yellow so bright, you could never mistake it for anything other than Daytona yellow.

Did you like these photographs of you?

The picture with the baby—I would say that was my favorite picture ever. Julian took beautiful pictures. Anybody who had their picture taken by Julian felt blessed.

How did you feel about the article?

I don’t remember the article. I remember the pictures.

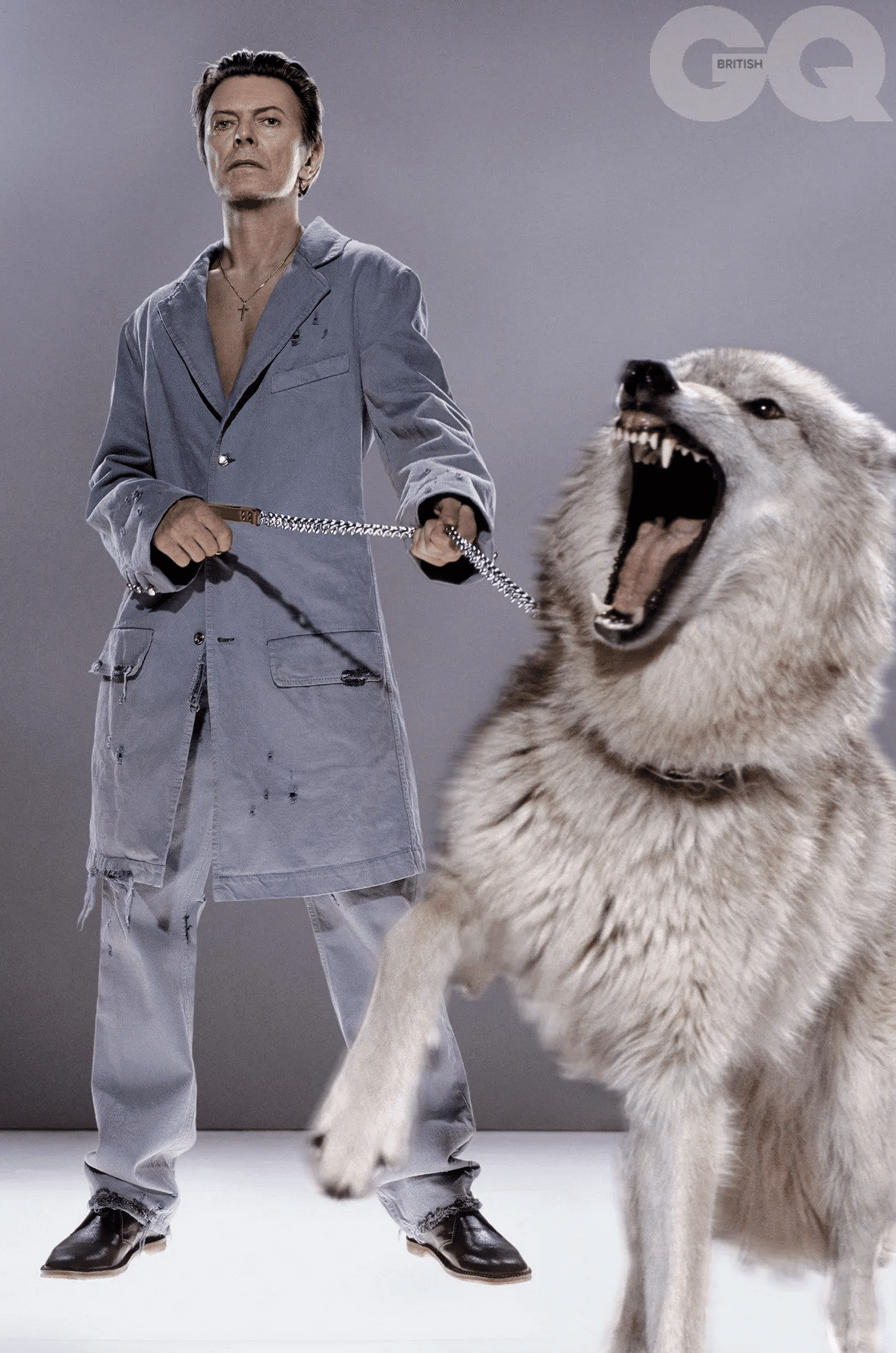

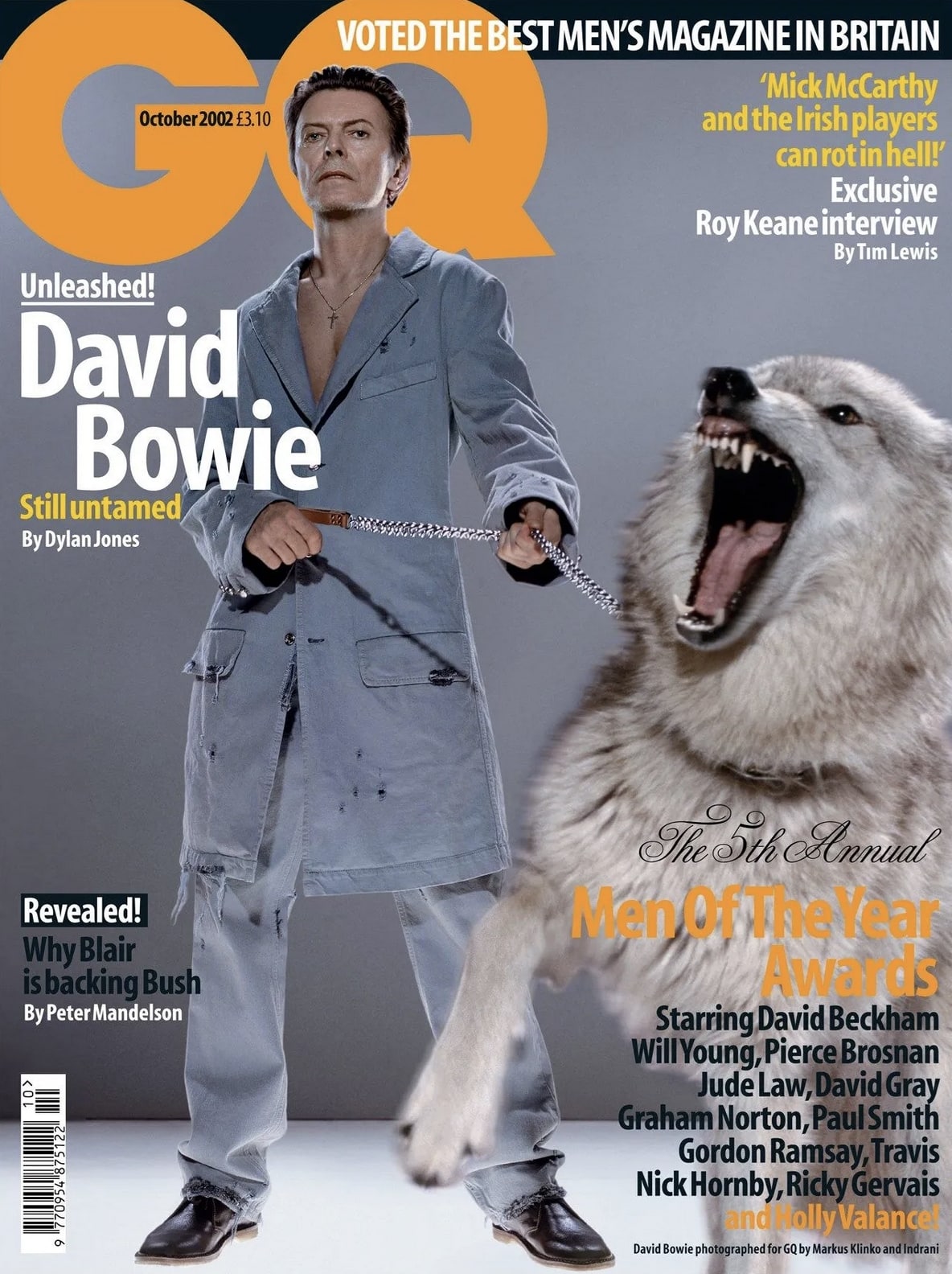

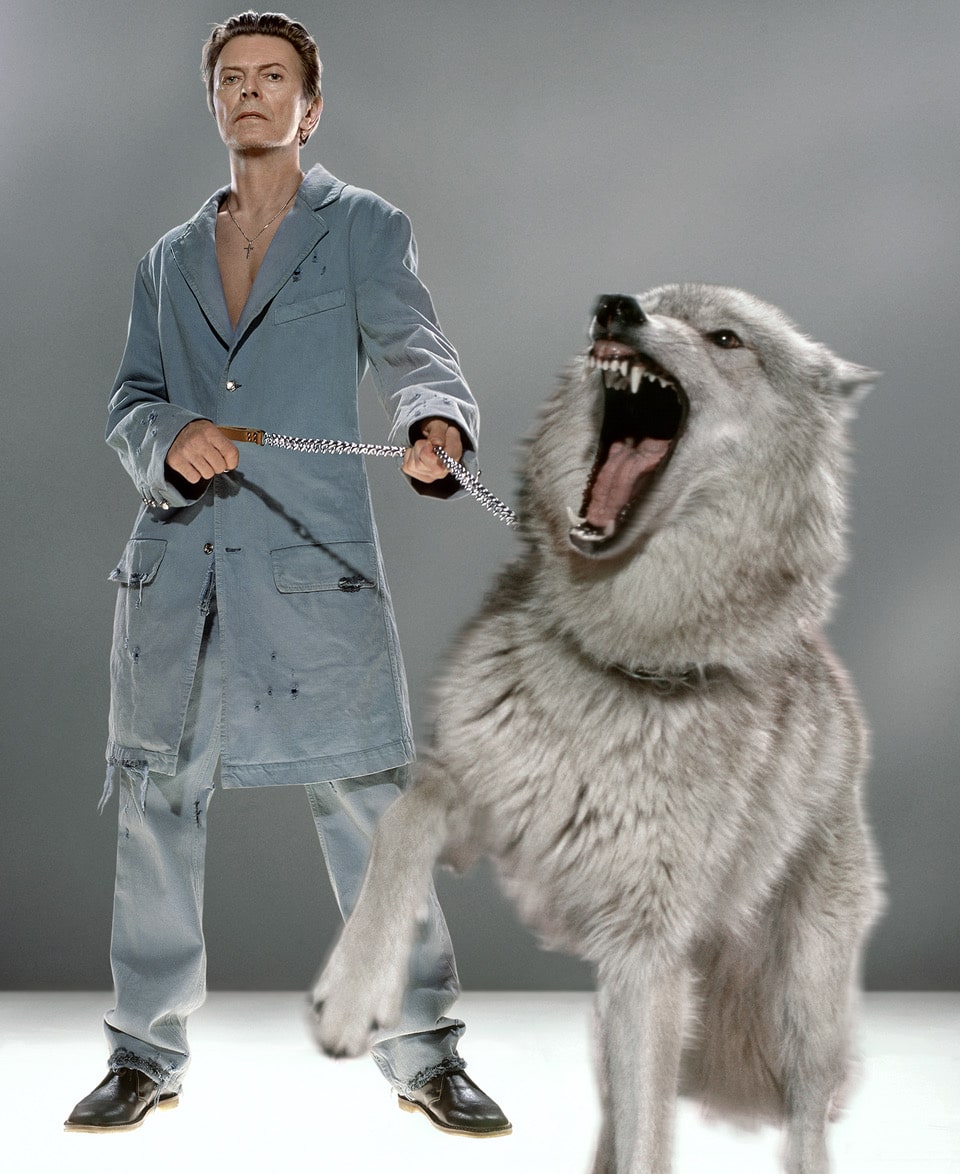

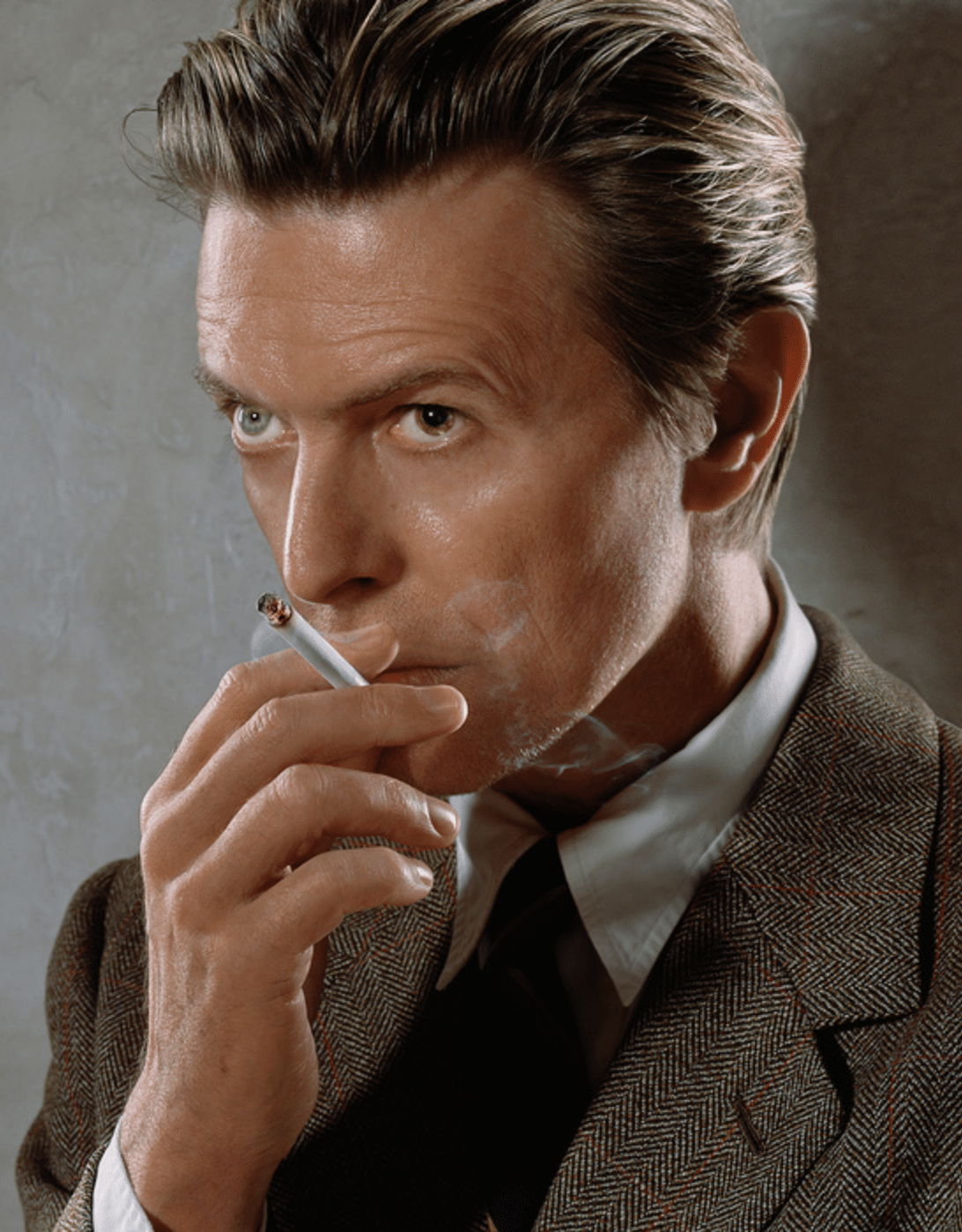

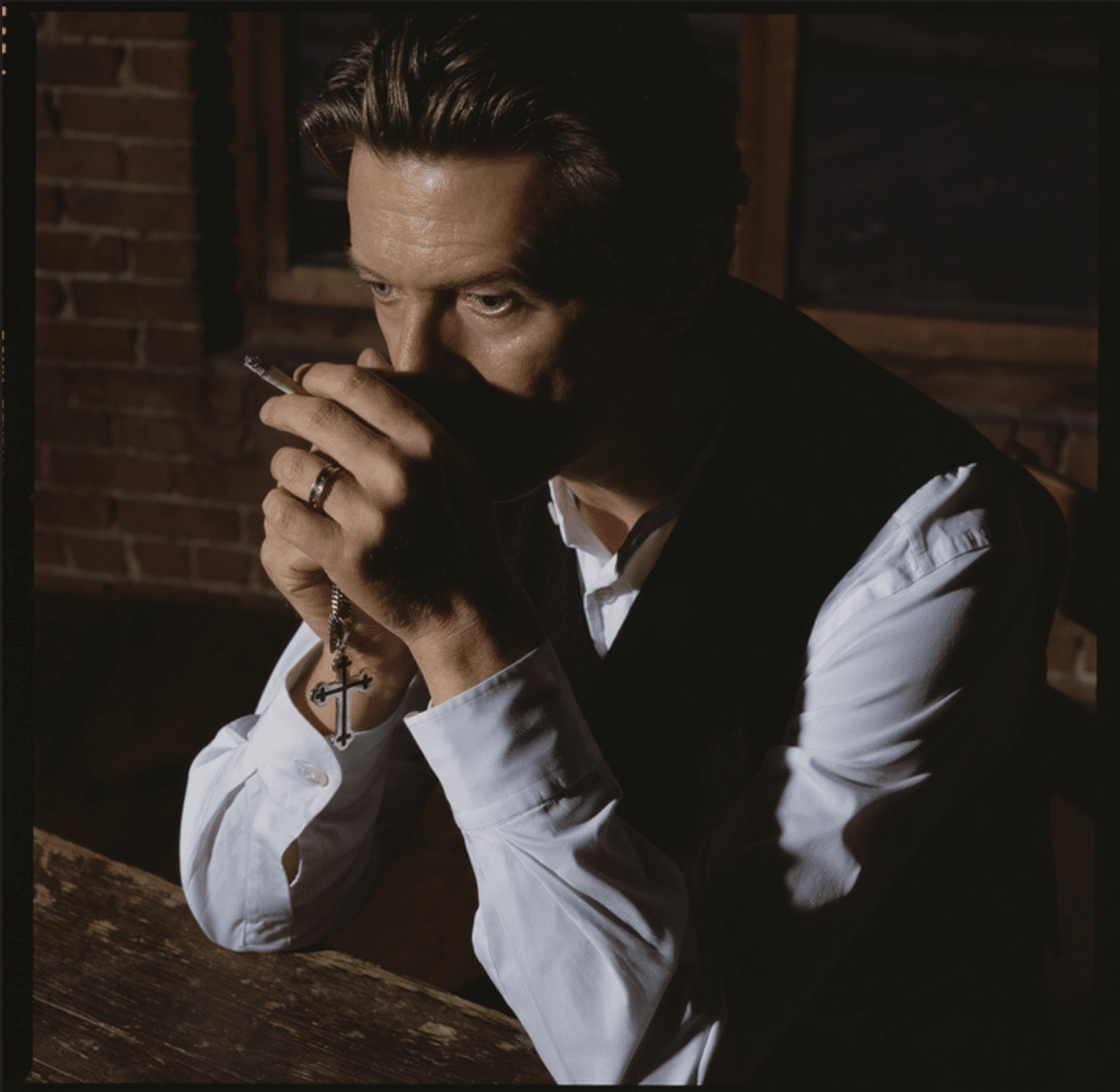

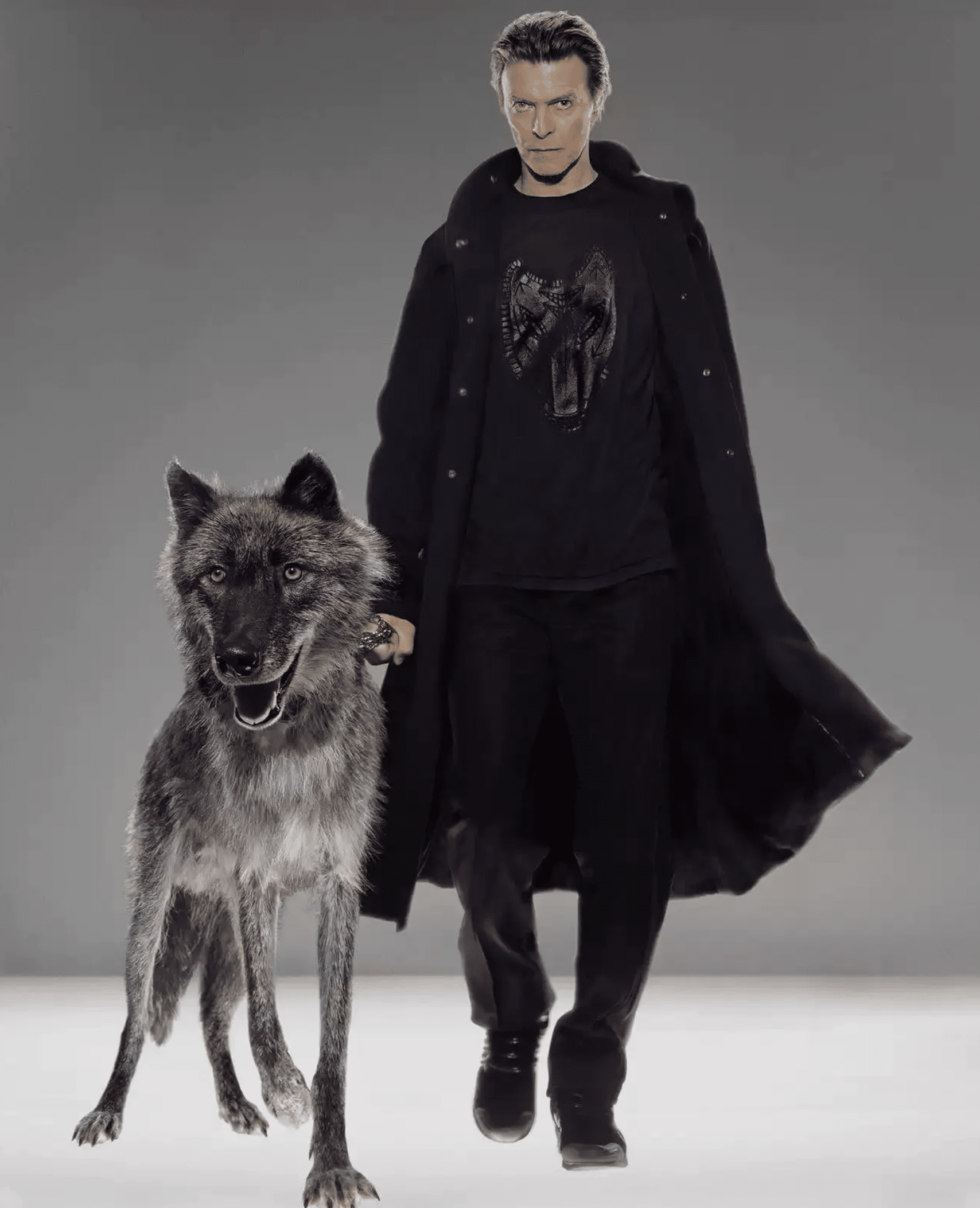

How we photographed David Bowie with wild wolves

Artists

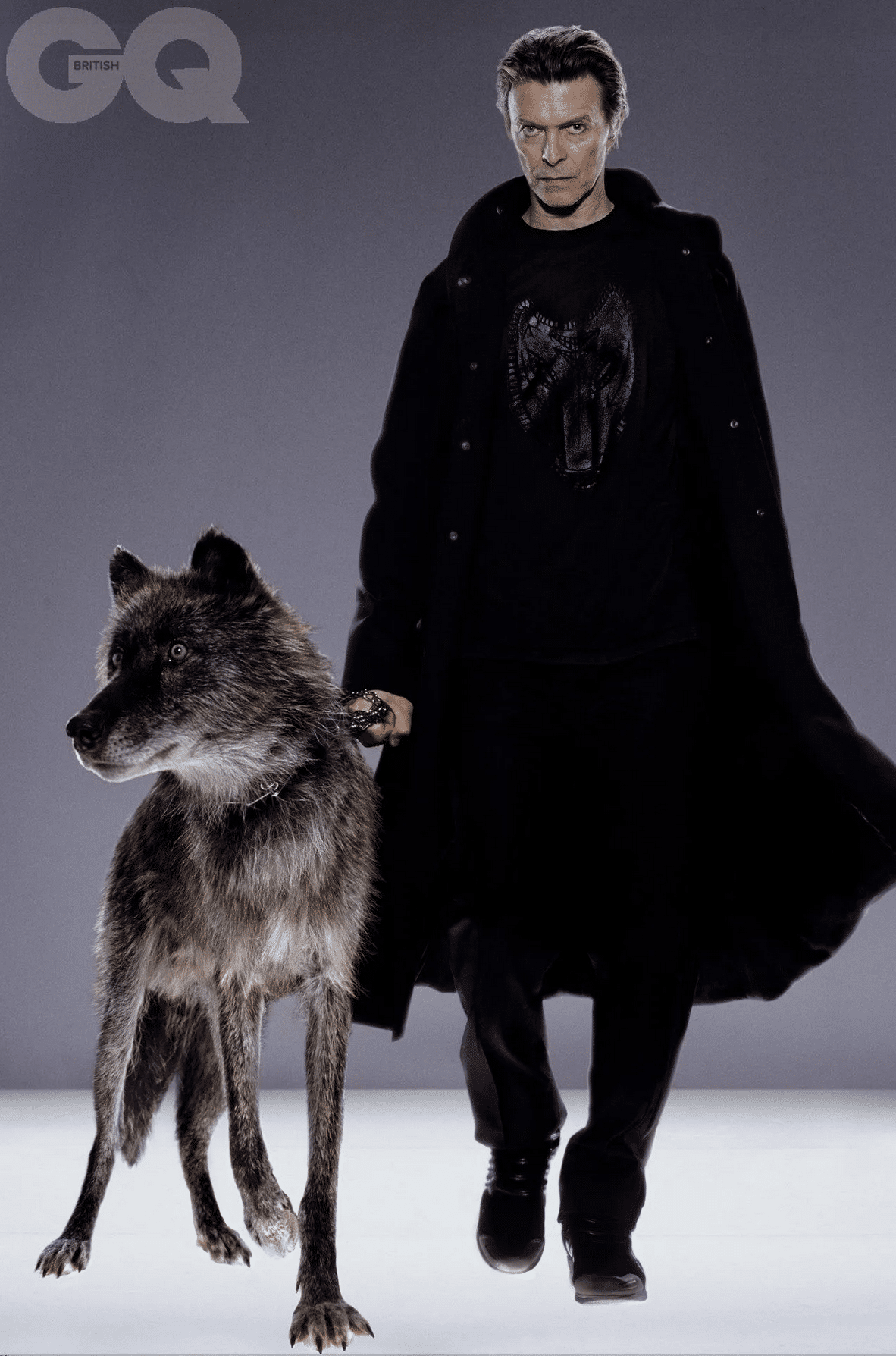

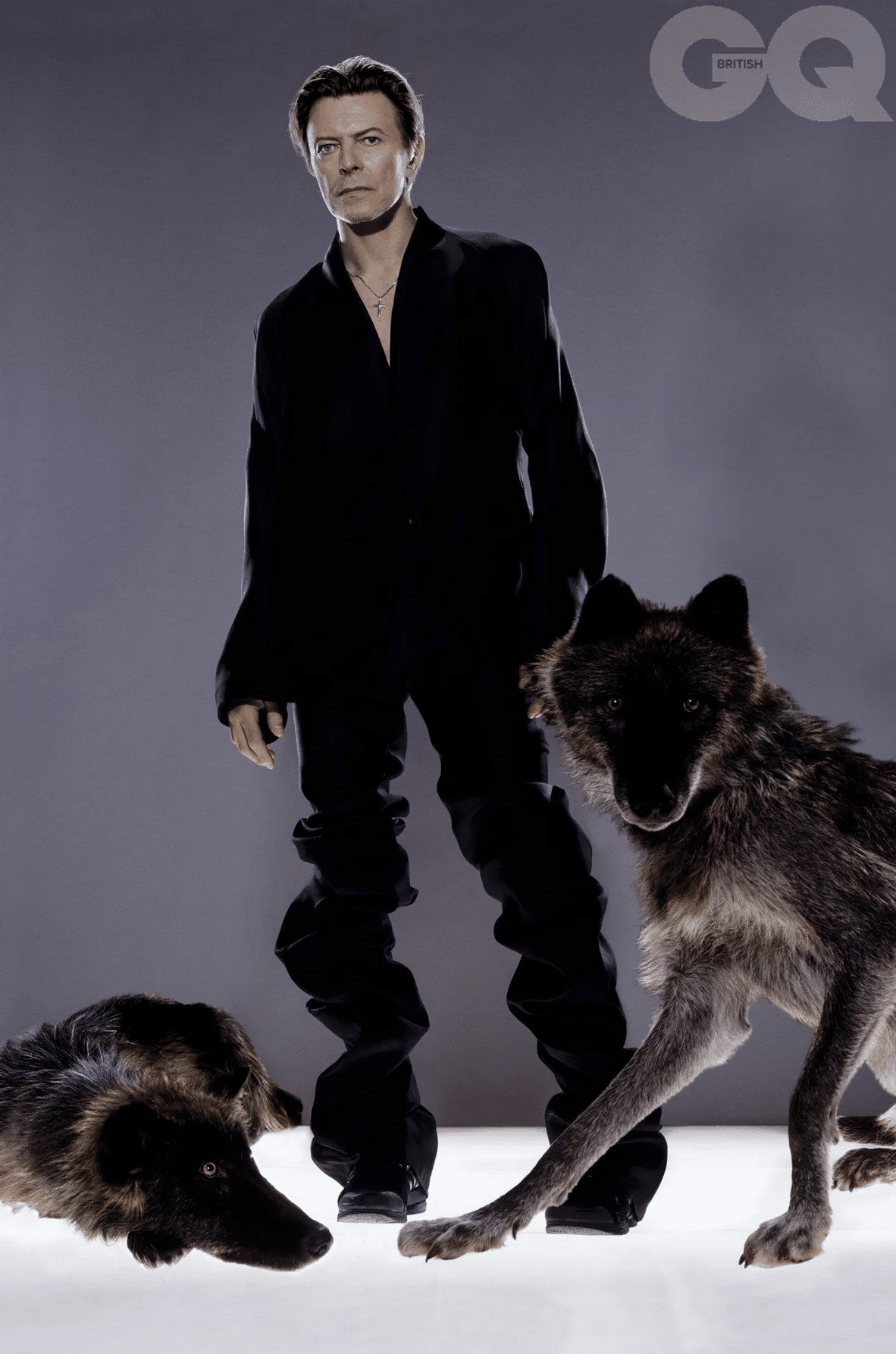

Renowned photographer Markus Klinko tells the story of how he came to photograph the legendary David Bowie with wild wolves for British GQ's October 2002 issue.

It was the late spring of 2001 when I met Angelina Jolie’s famous make up artist, Paul Starr, on a shoot for Interview magazine in New York. He asked me if I had ever worked with Iman, another client of his, and suggested that he would take my portfolio over to her house, just a few blocks down the street from my studio.

The next day, Iman called me on the phone and said that she wanted to meet me and talk about a project. I was very excited to see the legendary supermodel in-person and was anxious to hear what she had in mind. When she arrived at the studio, I was shocked that she was even more stunning than the photos. She was very complimentary of my work and explained that she had been working on her first book, I am Iman. She had contributions from virtually every great fashion photographer in the world already, from Helmut Newton to Steven Meisel, but she wanted me to shoot the cover of the book. I couldn’t be more flattered, but also felt the pressure to create something amazing with her. We scheduled the shoot for the following week.

Read more: How we photographed David Bowie with wild wolves

The session was very successful. She wore fabulous dresses sent over by Alexander McQueen. Iman took on the role of a fierce warrior Goddess and embodied it completely. A couple days later, Iman returned to the studio to take a look over the edits with me, and to my great surprise, David Bowie came along to help choose the cover. He was every bit as charismatic and extraordinary as one can imagine, but really kind and lovely to talk to. David was very involved in the selection process and had a great eye for imagery. Both of them loved the photos.

During the editing session, David casually mentioned that he might be working on a new album and that perhaps he would call me to talk about shooting the cover for it. That sounded a bit too good to be true, and while I was hopeful that this could happen, I did not get my hopes up too high.

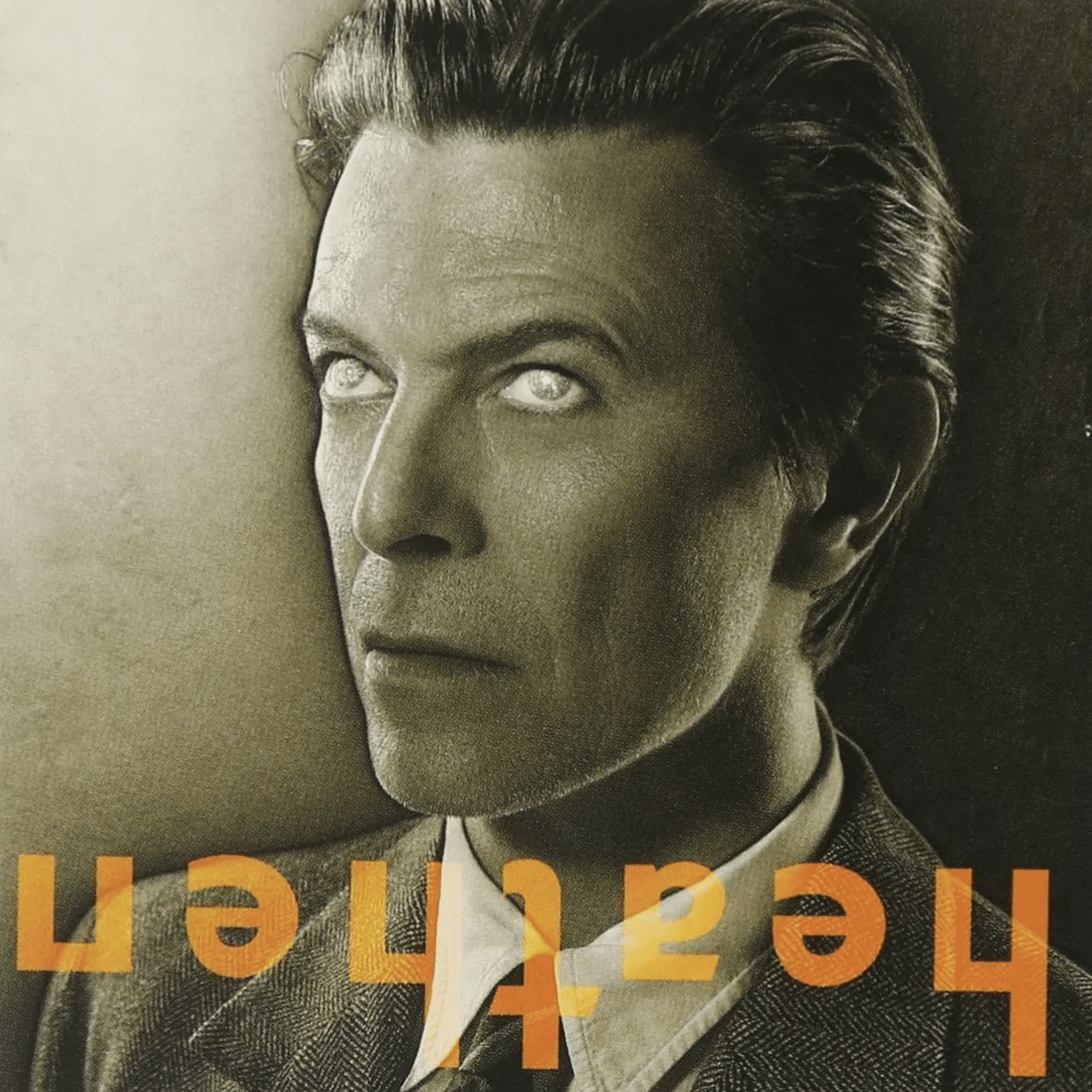

Meanwhile, the terrible events of 9/11 took place less than a mile from my studio, and for a little while I even forgot about the prospects of shooting my first David Bowie album cover. Yet, a few weeks after the tragedy, true to his word, Bowie called me. He is one of the very few celebrities that I have worked with who personally got involved, and was extremely communicative and very hands-on in the process. He asked if I could come over to a Broadway recording studio and listen to some tracks. I went over the next day. I wandered around the old, understated recording studio to find Bowie and his producer, Tony Visconti, in one of the rooms. Bowie said that wanted to play some of the new songs for me before discussing the album art. The mental image of Bowie sitting by a window, smoking cigarettes while his producer played the rough mixes from the board, is a memory that I could never forget. After listening to almost the entire album together, we started talking about the shoot. He had many ideas and was very precise about them.

David was very eager to get it all set up as quickly as possible and to shoot within a couple days. He returned to my studio the next day, and brought a series of early Man Ray images that he was very interested in referencing in some way or another. He wanted to be styled in Forties’s suits and wanted to get into the character of a blind man. At that time, most of my work was very colorful, but David was profoundly visionary and believed that it would be interesting for me to produce a series of mainly black and white album images, as well as some color images for press.

He is one of the most photogenic stars ever, and almost every single shot looked incredible. Bowie knew exactly what poses and expressions to do in order to portray the character we discussed. He was very carefree and fun to shoot.

During the following weeks, David often came by the studio to select and edit the photos. One day, he stopped by while I was shooting a British GQ editorial with a lot of male and female models running around in towels and he said, “This reminds me of the Seventies! And I remember nothing from the Seventies…” and then he laughed.

Heathen was released in 2002, and Bowie went on tour to promote the album. Around that time, I got a call from GQ in London, asking me to shoot David for their prestigious “Men of the Year” cover. Since Bowie was busy with the tour and was not available for a shoot within the deadline for the magazine, a creative solution had to be found.

I called up to David and asked him if he would trust me with creating a series of complex photocompositions, using a body double and several wild wolves. He immediately loved that idea, and said that I had carte blanche. My agent called the modeling agencies, and I decided on a young guy who had very much the stature and body shape of Bowie.

Next, I needed to find a bunch of wild wolves and get them to my Soho studio. Luckily, a prominent handler of wild animals for film and photo shoots was a huge David Bowie fan and agreed to bring the gorgeous beasts to New York. Our male model proved himself quite brave, as he worked it with the energetic and sometimes aggressive wolves. While his face looked nothing like Bowie, he was able to channel him through his body language. The images of David from the Heathen session and the shots of the body model and wolves were later combined by my post-production studio and have since become a favorite in GQ’s iconic history.

In the years following the Heathen and GQ shoots, I continued working with Iman on a regular basis, and saw David a couple of times. Once at Iman’s birthday party, he was running around their home and putting on great music to set a fun mood for everyone at the party. I brought over a huge print of Iman as a gift and they both loved it. It was very obvious how much he adored Iman. After his heart attack in 2005, I did not see him anymore.

Fast forward to 21 May 2013: at this time, I had moved to Los Angeles and was finishing up at the gym when I received an email marked “URGENT” from Bowie’s manager, letting me know that David wanted to speak to me. I rushed home to take his call, and was elated to learn that he wanted me to direct a video for his new single “Valentine’s Day.” Years earlier when we shot the Heathen artwork, I told Bowie that I would love to direct a video for the album and he said that it would be great but his new music was not mainstream enough to play on MTV so he didn’t see the point in making any videos. During those days, music videos really depended on MTV.

As I chatted on the phone with David for over an hour about his new video, it was just amazing how surprised he was at the success of this latest album, The Next Day. He said that he was not expecting that at all. With the creative freedom of Vevo and Youtube, he was excited to create videos again.

We did an animated portrait shoot, since many of his fans really wanted to be able to just watch him “without all the bells and whistles.” We shot the video in two days in New York. The song was about a mass shooting, and he wanted to reference the violence in a very subtle way. I had the idea to insert a flying bullet for a split second and if you look closely, there is a shadow of a person holding a machine gun.

My coffee table book, Icons, had just come out a few months prior to the video shoot featuring both David and Iman, with Iman writing the foreword for the book. David wanted a few copies of the book, and signed some as gifts. His spirits were very high and he was in a great mood. It was wonderful to work with him again after so many years, and see him full of creativity, energy, and excitement about the future.

Markus Klinko’s “Bowie Unseen” show opens in Basel, Switzerland on 24 March at Licht Feld gallery until 9 April and in LA at Mr Musichead gallery on Sunset Blvd on 19 May.

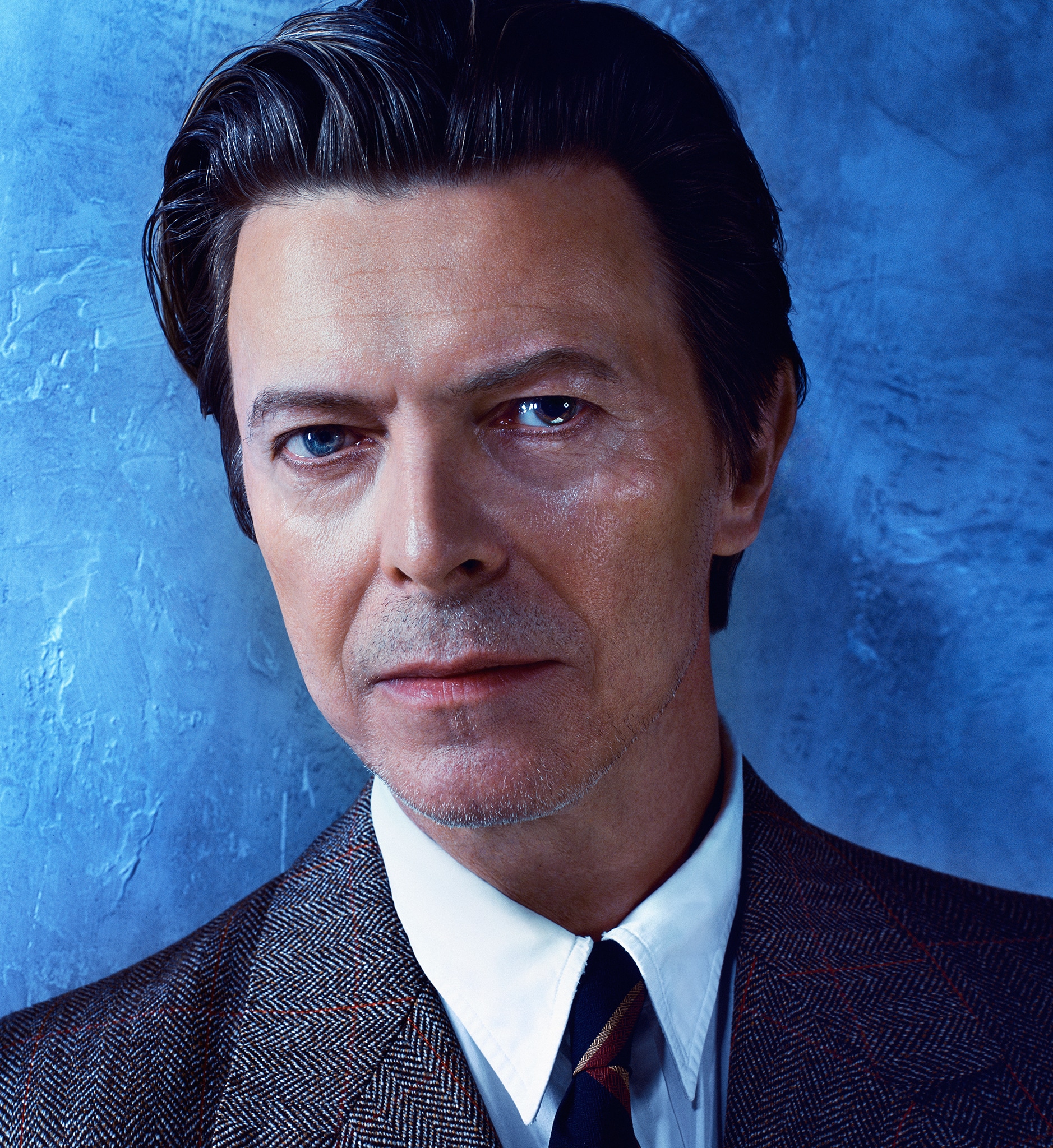

Markus Klinko’s Amazing Never-Before-Seen Photos of David Bowie

Artists

They're outtakes from a 2001 shoot that involved a pack of wolves.

In 2001, Markus Klinko was invited to photograph David Bowie. Now, in the wake of the beloved singer and artist’s unexpected passing, the unpublished images are finally coming to light, and are currently on view in”Bowie Unseen” at LA’s Mr MusicHead Gallery.

The photographer shot the album cover for Bowie’s 2002 record, Heathen, an eerie black and white image of the singer as a blind man. The current exhibition includes that photo, as well as over 20 never-before-seen outtakes from that day.

“It was a 9 to 5 shoot,” Klinko recalled in an interview with ABC. “We got so much done and, you know, I will never forget this session.”

Once we did the cover for Heathen—which took several hours and which he had very precisely mapped out in his head what he wanted—he then turned very playful and allowed me to have fun,” he added.

On the strength of that work, Klinko was asked to create the cover image for GQ‘s “Man of the Year” issue honoring Bowie. The resulting image shows the rock star fearlessly posing with a pack of wild wolves. Due to Bowie’s busy schedule and lack of availability for another shoot, Klinko was forced to use a body double with the wolves, carefully adding in the singer’s face from the photos taken for Heathen during post-production.

“Our male model proved himself quite brave, as he worked it with the energetic and sometimes aggressive wolves,” Klinko recalled in GQ earlier this year. “While his face looked nothing like Bowie, he was able to channel him through his body language.”

A portion of the proceeds from all works sold during Klinko’s exhibition will go to Gabrielle’s Angel Foundation for Cancer Research, in honor of the singer, who died from liver cancer.

See more of Klinko’s photos of Bowie below.

Markus Klinko’s “Bowie Unseen” is on view at Mr MusicHead Gallery, 7420 W. Sunset Blvd., Los Angeles, May 19–June 15, 2016.

Versace et Cube Art Fair exposent les œuvres du célèbre photographe Markus Klinko

by Katie Lister

Artists

Une trentaine d'œuvres, à la fois physiques et digitales, du photographe américain sont exposées dans la boutique Versace de Bruxelles.

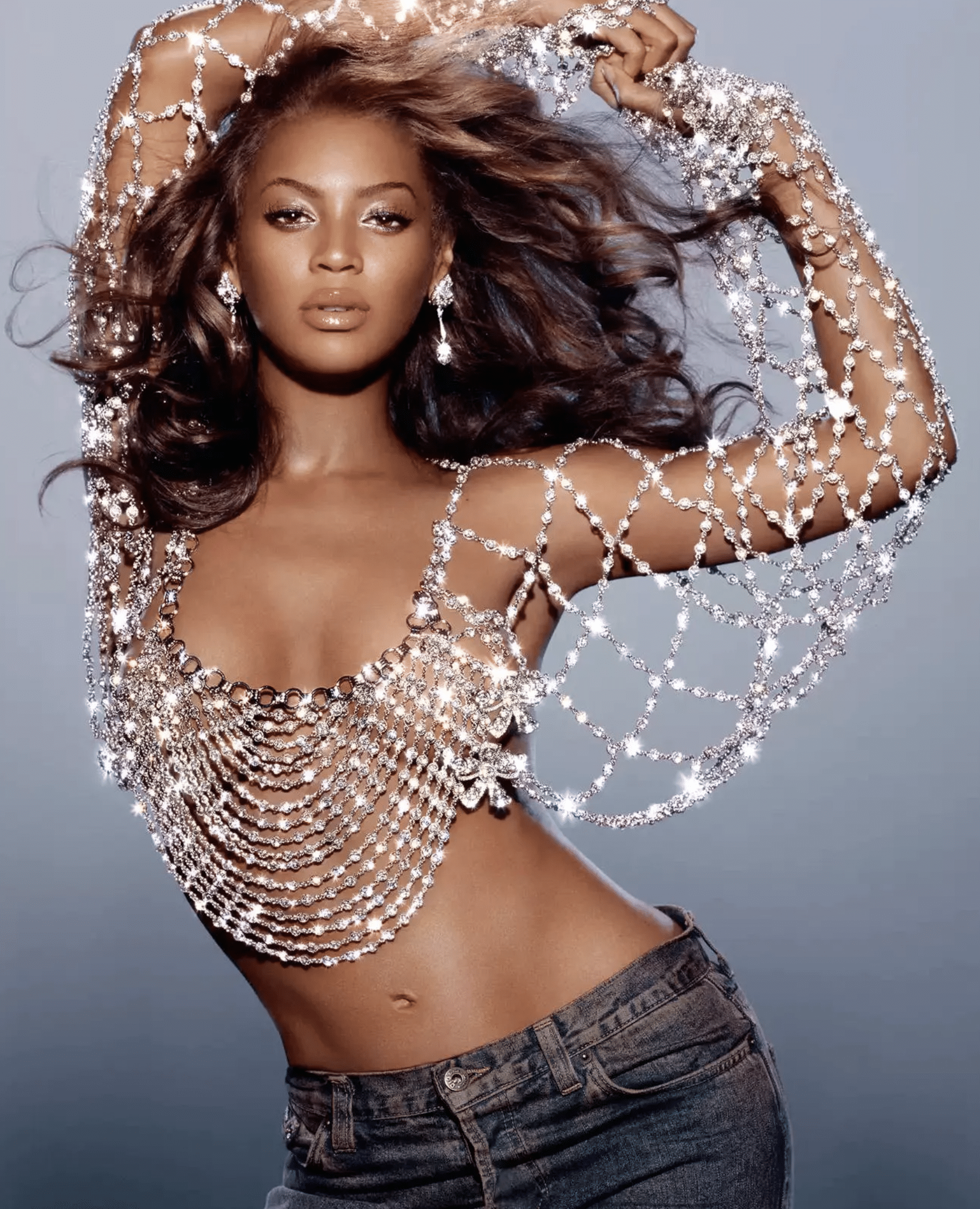

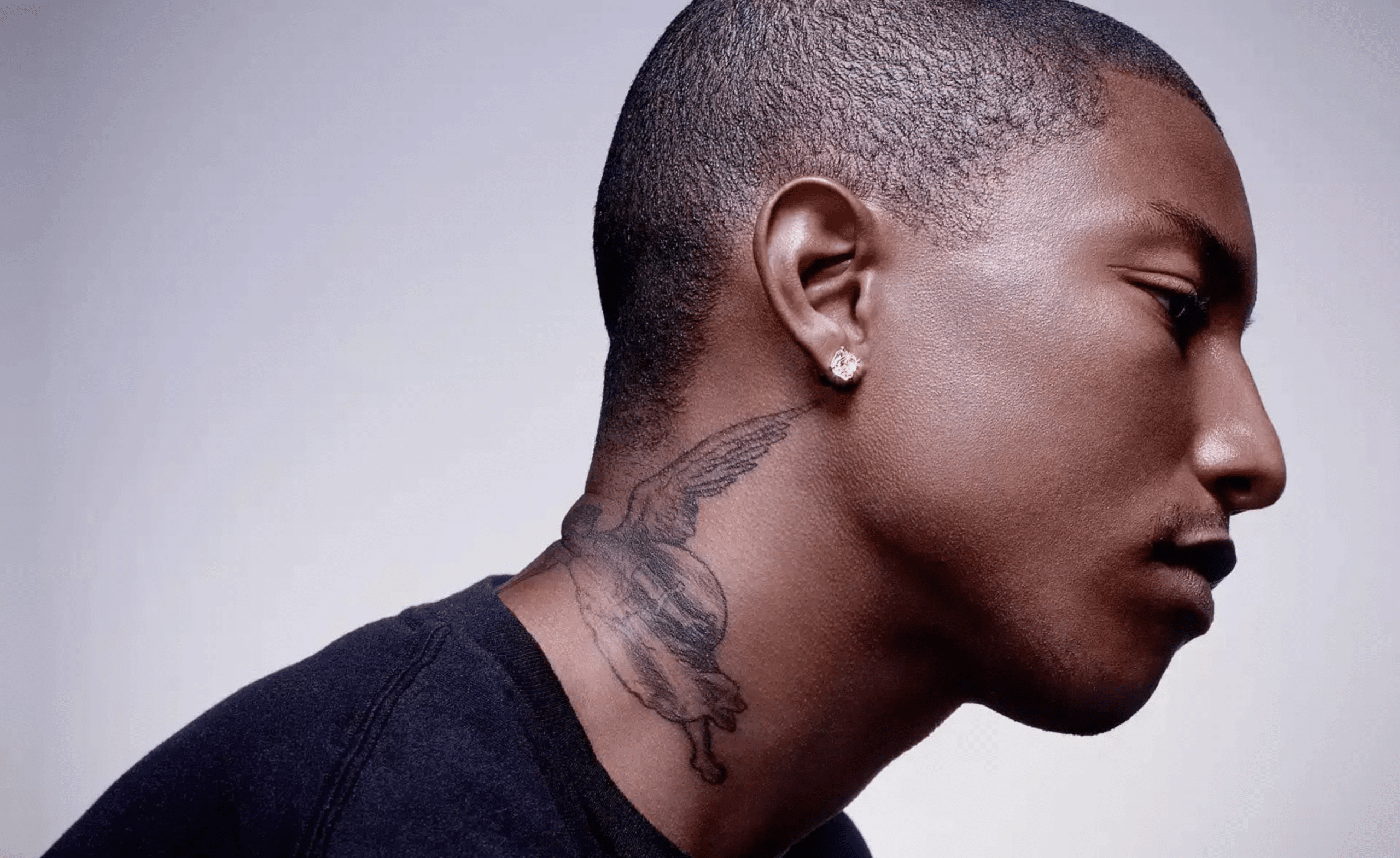

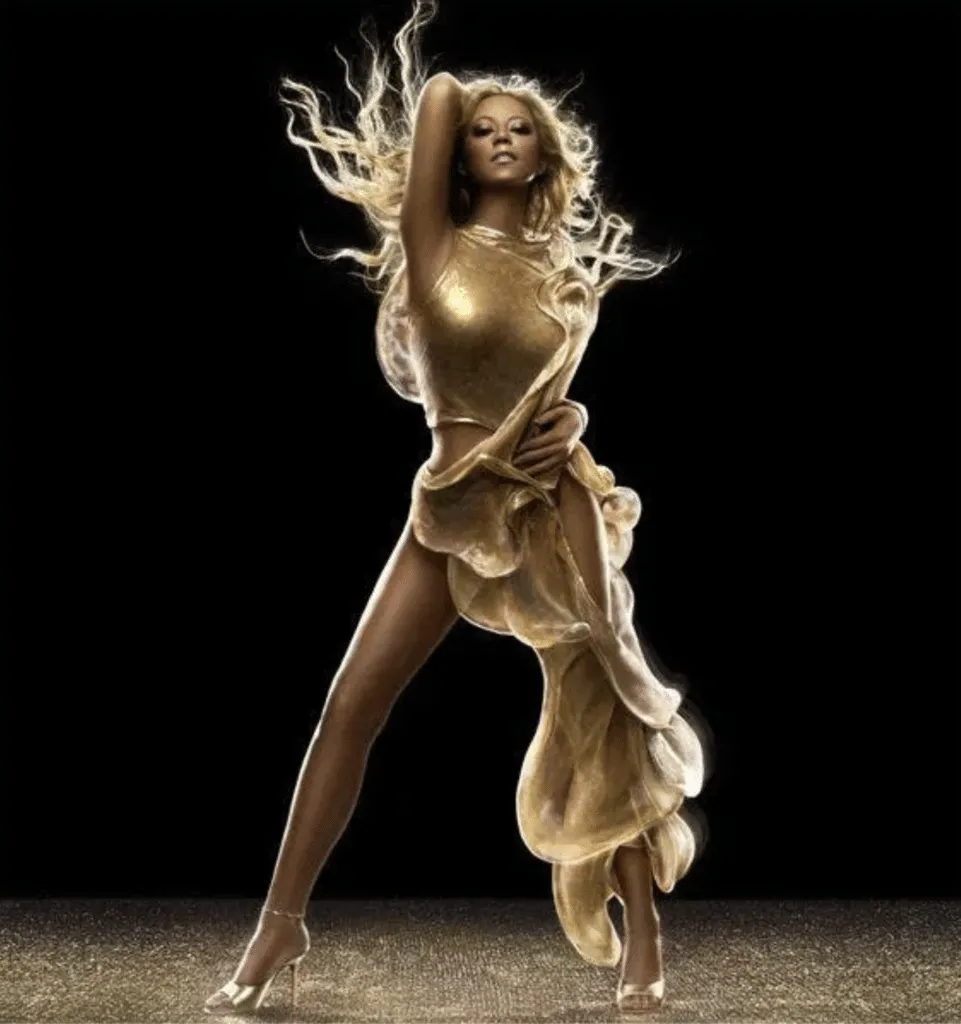

Considéré comme l’un des photographes les plus prolifiques des années 2000, Klinko a capturé des personnalités légendaires de la musique et du divertissement, notamment Beyoncé, Lady Gaga, Anne Hathaway, Jennifer Lopez, Britney Spears, Jay Z, Janet Jackson et David Bowie.

L’exposition organisée par la Cube Art Fair et orchestrée sur le plan curatorial par Vogelsang Gallery, qui représente Klinko, coïncide avec le Uptown Tour, un parcours qui promeut l’art et le design dans des lieux d’exception de la capitale européenne.

Les œuvres photographiques tendance de Klinko sont en parfaite adéquation avec Versace, dont l’ADN extravagant et créatif et sa définition du luxe se marient avec les tirages d’art contemporain colorés et audacieux de Markus Klinko. Les personnages emblématiques dont il capture les esprits ne sont pas seulement connus pour leur savoir-faire artistique, mais aussi pour la façon dont ils repoussent les limites de leur sens du style et de leur identité de mode.

Cube Art Fair occupe habituellement l’espace public de manière spectaculaire en présentant des œuvres d’art contemporain dans les rues de villes comme New York, Miami ou Bruxelles. Ses expositions, diffusées sur de gigantesque panneaux digitaux de 2000 mètres carrés sur Times Square, ou projetées sur des gratte-ciel de 120 mètres de haut à Miami, ont valu à la foire lors de ses neuf précédentes éditions l’acclamation de la presse internationale qualifiant “The World’s Largest Public Art Fair” (la plus grande foire d’art publique du monde). Aujourd’hui c’est en occupant les murs de la boutique Versace, que la Cube Art Fair a décidé de faire vivre les œuvres de ses artistes.

“Versace est à la pointe de la créativité dans le domaine de la mode, et je suis ravi que notre collaboration avec Cube Art Fair apporte le meilleur de la créativité dans l’art contemporain au sein de leur boutique. La curation de l’exposition Markus Klinko a été un processus passionnant, ses œuvres capturent véritablement l’esprit Versace », déclare Gregoire Vogelsang, fondateur de Cube Art Fair et propriétaire de la galerie éponyme Vogelsang Gallery.

39th Annual Smith Nature Symposium Awards Dinner

Markus Klinko est un exemple de la façon dont les photographes – et les créatifs qui travaillent dans le monde commercial – peuvent réussir aussi bien, sinon plus, dans le domaine des beaux-arts : Ses œuvres se vendent à des prix record et il est représenté par plusieurs musées et galeries internationales. Plus tôt cette année, le Fotografiska Museum de New York a présenté son travail.

« Je suis honoré que Cube Art Fair ait choisi d’organiser cette exposition en collaboration avec Versace. Je suis tombé amoureux de Versace dans les années 1980. J’adore la marque, et avoir mon travail dans leur magasin phare de cette capitale européenne est un rêve devenu réalité !“, a ajouté Markus Klinko.

Son travail sera présenté dans la prochaine série HBO, The Idol, du créateur Euphoria James Levinson, et mettant en vedette The Weeknd (qui, nous dit Artnet, est également un collectionneur du travail de Klinko).

Les œuvres sont en vente via Vogelsang Gallery: info@vogelsanggallery.com | +1.646.322.7935 ou +32 485 148 845

Versace Bruxelles:

Adresse : Bd de Waterloo 7, 1000 Bruxelles, Belgique

Heures d’ouverture :

du lundi au samedi : de 10h00 à 18h30

Inspiring Change: SeaLegacy’s Cristina Mittermeier and Paul Nicklen Honored at Brushwood Center’s Smith Nature Symposium Awards Dinner

Artists

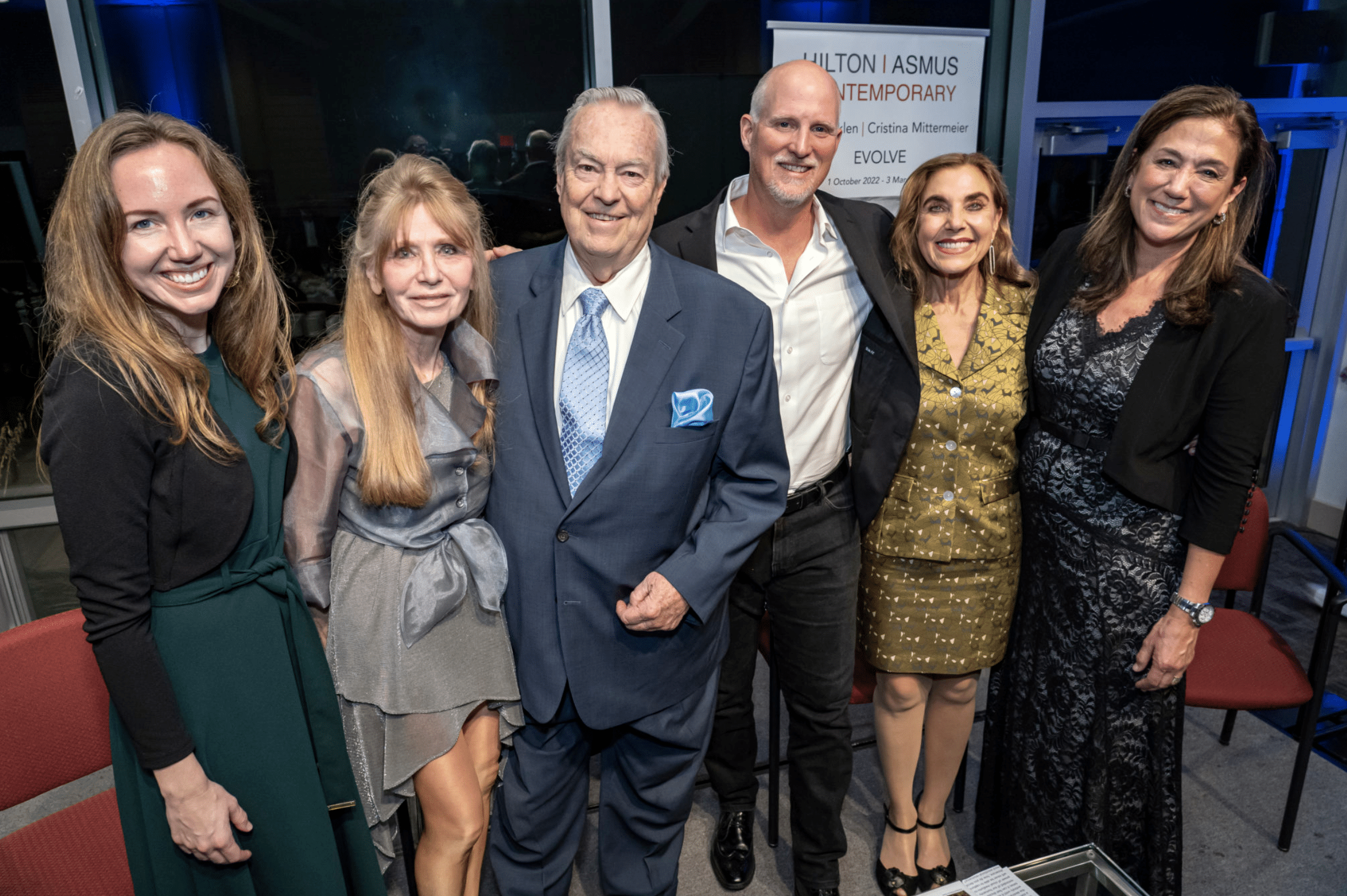

On September 30, the Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods hosted its 39th annual Smith Nature Symposium, “Inspiring Change,” at the Greenbelt Cultural Center in North Chicago. Nearly 200 people attended the event to honor the extraordinary leadership of Cristina Mittermeier and Paul Nicklen and their impact on ocean justice and conservation as photographers, marine biologists, and founders of SeaLegacy.

Every year, the Smith Nature Symposium celebrates nature and those who have made a meaningful contribution to the conservation of the natural world. The first award of the night, the Environmental Youth Leadership Award, went to Nalani Hill, a 16-year-old student from Lake Forest Academy nominated by Brushwood Center partner, Cool Learning Experience (CLE).

Later in the night, Mittermeier and Nicklen earned the Distinguished Environmental Leadership Award. The two, who are partners in life and business, work on the front lines of conservation. They started SeaLegacy in 2014, a non-profit to propel ocean conservation through visual storytelling, impact campaigns, and funding projects.

Mittermeier and Nicklen are photographers creating stunning artistry and advocacy for their environment through their work. Evolve, the photography of Mittermeier and Nicklen, is available for viewing at the Brushwood Center Gallery until October 30, 2022.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Ciab72NL0hj/?utm_source=ig_embed&utm_campaign=loading

“Each year, we honor those making an environmental impact. But also try to bring in award recipients who have an art practice because Brushwood Center focuses on health equity and well-being through accessing nature and the arts,” says Mirja Spooner Haffner, Director of Development at Brushwood Center. “The fact that [Mittermeier and Nicklen] touched upon those two themes is significant for our annual fundraiser.”

The Smith Nature Symposium is Brushwood Center’s largest fundraiser. They raised $140,000 to benefit Brushwood Center’s programs for children, families, professionals, and veterans throughout the community. Of the total funds raised, $53,000 came from the night’s paddle raise, which is double what they received from their last in-person fundraiser three years ago. There was also a match opportunity through a Chicago Community Trust grant for up to $25,000, bringing the in-room total to $78,000.

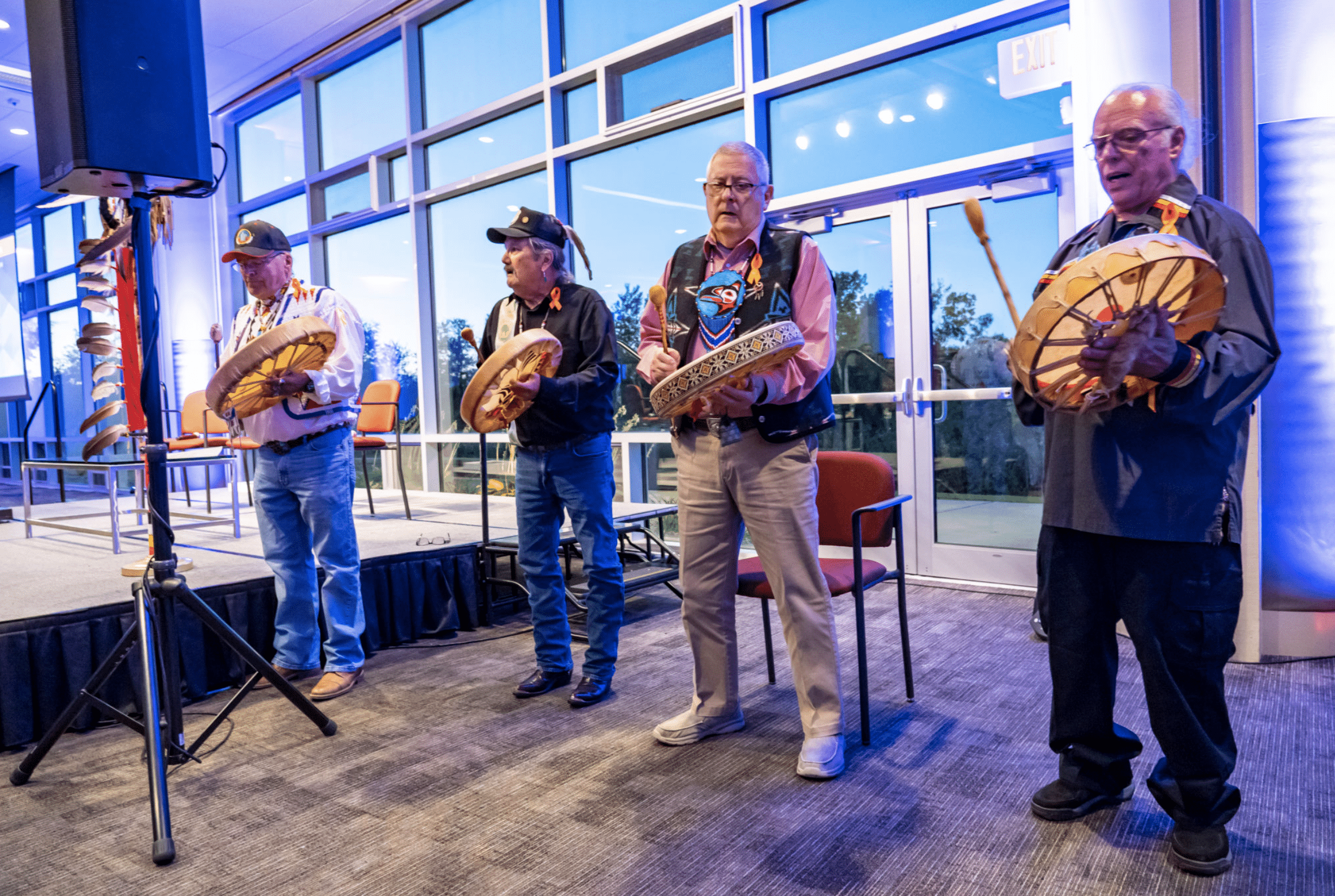

The evening started with a cocktail reception followed by the dinner procession with entertainment from Seven Springs Drums. The event, led by acclaimed emcees, television journalist Bill Kurtis and producer Donna LaPietra, included a land acknowledgment by Michael Pamonicutt and welcoming remarks from Host Committee Co-Chairs Disha Narang and Amy Heinrich.

Numerous esteemed guests attended the dinner, including Vicky and George Ranney of the Ryerson family, who donated Brushwood Center’s building and the land of Ryerson Woods. Also in attendance were SeaLegacy CEO Jack Lighton and their Board Chair Ryan Kissick. The night also welcomed Arica Hilton and Sven Asmus of Hilton|Asmus Contemporary, who, thanks to the work of Brushwood Center Chair Gail Sturm, partnered with Brushwood to present Evolve.

Out of respect for the vegan honorees who work to support the environment and ocean, all of the food from the night’s dinner were gluten-free, dairy-free, and vegan and came from local farms. The local farms included Temple Organics Farm in Old Mill Creek, Illinois, Mick Klug Farm in St. Joseph, Michigan, and Herban Produce Farm in Chicago, Illinois. There was also a strolling dessert buffet with assorted mini cupcakes, cookies, brownies, and a Mexican cinnamon churro station.

The support of generous sponsors made the night possible. Ambassador sponsors included Amy and Rob Heinrich, Michael M. Levin and family, Jean Meilinger, John Schneider, Adele Simmons, A. Gail and William Sturm.

Program sponsors included The Chicago Community Trust, John and Kathleen Schreiber Foundation, Illinois Arts Council Agency, Illinois Humanities, Mid-America Arts Alliance, Oberweiler Foundation and more.

39th Annual Smith Nature Symposium Awards Dinner

Artists

RYERSON WOODS – Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods is honoring Paul Nicklen and Cristina Mittermeier, two of the world’s most celebrated photographers and conservationists, with the 2022 Distinguished Environmental Leadership Award at the 39th annual Smith Nature Symposium Awards Ceremony at Brushwood Center.

The ceremony will be Sept. 30. In collaboration with Hilton Asmus Contemporary Gallery, their work will be on exhibition at Brushwood Center’s Gallery from Sept. 12 through Oct. 30.

“We are humbled by both Paul and Cristina’s significant accomplishments on behalf of people and the planet, embodied through their stunning artistry, bold leadership and advocacy for the environment,” said Gail Sturm, board chair at Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods. “We are so inspired by their storytelling, incredible body of art and their advocacy for ocean protection through their nonprofit, SeaLegacy. Their passion for this planet and belief in the power of people to come together and create change is kin to the spirit of Brushwood Center.”

Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods works collaboratively with community partners, artists, health care providers and scientists to improve health equity and access to nature in Lake County and the Chicago region. Brushwood Center engages people with the outdoors through the arts, environmental education and community action. Brushwood Center’s programs focus on youth, families, veterans and those facing racial and economic injustices.

Nicklen is a Canadian photographer, filmmaker and marine biologist who has documented the beauty and plight of the planet for more than 25 years. He was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame in 2019 and in that same year was appointed to the Order of Canada. He has done 23 assignments for National Geographic and won many prestigious awards.

Mittermeier is a world-renowned conservationist and photographer who knows that stunning visual storytelling is the key to unlocking critical action to help heal the oceans and save the planet. She founded the International League of Conservation Photographers in 2005, is a contributing photographer at National Geographic and was named one of the 100 Latinos Most Committed to Climate Action in 2021.

Working together on the front lines of conservation, often onboard the SeaLegacy 1, Nicklen and Mittermeier also are partners in life. Both are marine biologists, and earlier this year they received an Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts, Honoris Causa, from Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada. In 2014, they co-founded SeaLegacy, a nonprofit organization that propelled ocean conservation onto the world stage through the power of visual storytelling, impact campaigns and the funding of sustainability projects. Guided by science and driven by purpose, SeaLegacy is the global marketing, education and communication agency for the ocean.

“To be recognized by Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods and to be acknowledged alongside people whose work inspires us greatly is a true honor,” Mittermeier said in a news release. “Paul and I look forward to sharing our work, our vision and our dedication to using the authentic beauty of art and storytelling as an invitation to take action to protect our one and only home. We know that Brushwood shares this mission with us and that working together is the only path to true and positive impact.”

The Distinguished Environmental Leadership Award was first presented in 1984 to Roger Tory Peterson, the esteemed American naturalist, ornithologist, artist and educator.

The awards ceremony takes place at the Lake County Forest Preserve’s Greenbelt Cultural Center in North Chicago, a green building and gathering space designed by environmental architect Bill Sturm.

Brushwood will display selections from the couple’s newest exhibition “Evolve, The Photography of Cristina Mittermeier and Paul Nicklen.” As the world and its inhabitants adapt with the ebb and flow of constant change, so, too, does an artist’s view. From a bird’s-eye view of the meandering formations of the Colorado River that mimic patterns of branching trees and human lungs to the lushness of what looks like an underwater painting celebrating the layers of life beneath the water’s surface, all is connected. “Evolve” is the artists’ journey as witness and passionate defender to the natural resilience and determination of a planet on which all life must coexist.

“Evolve” includes the first selections from Nicklen’s new Delta Series ahead of its premier at Art Basel in Miami later this year. It also includes never before seen work from Mittermeier.

September 2, 2022

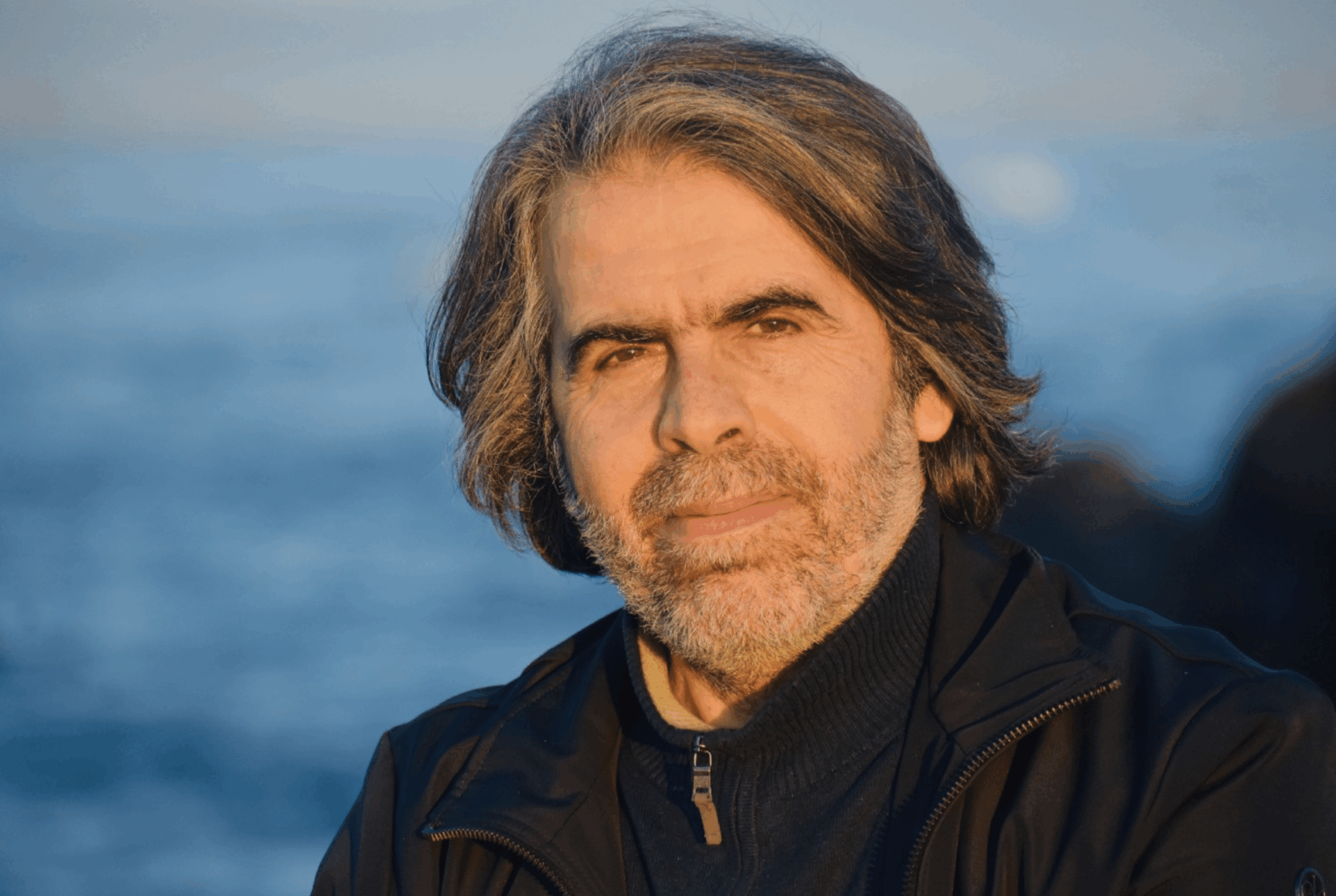

Language and Perspective: An Interview with Osama Esber

Osama Esber, born in Jableh, Syria, is a widely published author of poetry and short stories. He currently lives in exile in the United States. Esber has published five volumes of poetry in Arabic and has recently begun to write and publish poems in English. He has also been an active and prolific translator of works by Henry Miller, Toni Morrison, Michael Ondaatje, Noam Chomsky, Seamus Heaney, Nadine Gordimer, and Raymond Carver. Since moving to California, he has become a skilled photographer, producing powerful and unexpected images.

By Sophia Maas

You’ve translated many works into Arabic, so my first question is: Why translation? Who are you hoping to reach?

Translation, for me, is about learning. Of course we could talk about words as a source of income, but this is something else. I would like to talk about translation and how I approach it. By translating a book, for example from English into Arabic, you learn from it. You help a general readership get access to a different culture and a different experience of reading. I always learn from writers. For example, when I translated Raymond Carver’s work, I was able to understand things from a different perspective. When people talk about Carver’s work, they call his work “dirty realism.” I don’t like that term. He and other writers have opened my eyes to the richness of language. You find some people write fiction with the spirit of poetry. You find people open up to the experience of poetry. When I translate other people into Arabic I have to ask myself how they see their own world.

Writers learn from each other. I remember when I translated Raymond Carver I had a lot of feedback from other short story writers. They said it was helpful even for them to learn more about the art of short story writing. Translation for me is the noblest way to cross borders. What we know about each other comes through the media. Media is concerned with the political, and certain things don’t come through that as it can through short stories. You can gain a deeper understanding of the essence of American culture — what I consider to be creative literature — and can cross borders and get rid of prejudice and see culture through a deep lens of communication. It is a kind of understanding of one another. Translation can be defined as a deeper tool of communication.

What draws you to translate certain works and not others? What was your favorite work to translate?

This is an interesting question. Sometimes when we translate we are controlled by the market. When I was living in Syria I had a friend with a publishing house. I was at the beginning of my life as a writer, and I was studying American and English literature at university. I had access to writers who write in English, and I always like to choose a book that I like. But the question is why do you like the book? It helps you understand reality from a different perspective. Writers always talk about reality from an unfamiliar angle, and it always fascinated me. I always wanted to translate a work that moves in the same direction. I can mention two books that move in this level. One is The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje. I translated the book before it became famous, so I can say that I translated it because I like the way it tells stories in a rich and powerful way. I also enjoy a book called Einstein’s Dreams by Alan Lightman. It was written by a scientist who became a novelist. The way the book was written, by a scientific mind, has powerful imagination behind it. The language was amazing and evocative. It’s one of the reasons I choose certain books to talk about. This applies also to another publisher who bought the rights to publish the complete fictions of Raymond Carver. I translated the first book, Cathedral, because it can teach fiction writers to think of the world in unique ways. It can help writers understand the process of fiction and the creative writing that goes into fiction. These are the motives behind my choices of translation.

What do you want to say that you feel can’t be said in any way but through poetry?

For me, poetry is not about what I feel directly. What I feel personally is something personal. When we read something like T. S. Eliot or Mary Oliver we feel that the emotion expressed in the poetry is ours. It means that poetry is not about personal direct emotions but collective emotions. This means, for me, that poetry is a vision. René Char says that poetry is always a search for a word that always needs to be searched for. T. S. Eliot says, “I’ll show you fear in a handful of dust.” He talks about his view of the collapse of civilization. It’s said in a vertical way, not a horizontal way. For me, poetry is not always about the self. It is also about the other. What I want to do in poetry, personally speaking, is to be able to write and explore myself, but within a collective context in an unprecedented way. It is difficult to describe how this may happen. Poetry is about how you use language, the styles you use that no one else is using. It is about the difference in style. Compared to prose and other literary forms, poetry is a form to go beyond the norm and the known. It goes beyond the limits of a certain language. If I can talk about love in a way that no other poet has talked about or make it unfamiliar, then that is what I want to do. It is always a search for the things you are unable to say in normal language or the familiar language. No matter who reads a poem, they will find something personal in it. The personal is always in poetry, because it is your personal way of writing. That is your style. The personal is very important in poetry.

Your poetry is in both Arabic and English. How do both languages compliment or limit your artistic or poetic expression?

I originally write my poems in Arabic. I don’t write my poetry in English. As a writer I only find myself in Arabic. It is the language of my blood. I cannot write poetry in English originally. Language is about culture and the mindset through which you see the world. I see myself in Arabic. I can be more creative in it, not because it is more important than English, but because I was born there, and English is a language I have learned. I learned English because of translation. Sometimes you get a chance to be known in a foreign language, though it is not easy.

I saw that you’ve recently gotten invested in photography. What are you trying to express through photography? Is it another avenue of storytelling for you?

There’s a story about my interest in photography I would like to tell you. In 2013 I was living in Chicago and I was invited by the Italian renowned artist Marco Nereo Rotelli who had an installation at the time called Light and Sound. The idea was to transform the facade of the Field Museum in Chicago into a poetic image of Dante’s Divine Comedy. He invited a number of poets to write poems inspired by the Divine Comedy. I wrote a poem about the Syrian war and the hell it created, and when we met later for dinner, he looked at me and told me that I should take photographs and write poems about them. He talked about the relation between poetry and photography and writing poems inspired by photos. I started trying and I found that I related to photographers. I started looking at the visual world in a different way. Anyone can take a photo now. Anyone can press a button. But that is not photography. To take an artistic photograph there is an inspiration, something I can’t define in realistic terms. I can’t see it in the normal state of walking around. Capturing a good photograph is like writing a poem. It is a fleeting thing that you have to capture. In photography, like poetry, there is inspiration. It’s more technical, but it’s still about inspiration. I believe the most important thing about photography is the eye and how it sees things. I’m working on a photographic project about Chicago. You are a wanderer with your camera, you think of things as a photographer. I’m planning my next exhibition and working on it. On my Facebook, when I post a photo, I also write a poem about it. Photography has helped me in a way move away from trying to rationalize things logically. The photograph has saved me from being trapped under the influence of great literary giants. It helped me see poetry in a different way.

What do you find most inspiring about your current work in progress?

What I find interesting and inspiring is the struggle to achieve it. I’m working on poems right now that I feel needs more work. There’s a feeling of imperfection that motivates you and makes me excited about going back to rewrite. There’s a lot of confusion, but when you work, it starts to make sense. Arabic has a tradition going back more than two thousands of years of poetry being a high status symbol. To have a foothold here, to be regarded as a good poet, is something that happens after a long process. You have to struggle with language, you have to write and rewrite. This process makes the magic of writing, and that’s what I think is interesting about it. Something else, now that I live in the United States and my country is too far, this feeling of distance is also very interesting. It helps me see things in a different light that I was unable to see when I was living in the culture.

What keeps pushing you to create?

It’s the feeling that the great book that I’m dreaming of is not written yet. In a sense, writing is an act of searching for perfection. But writing is always related to imperfection. When you write a poem or a book you ask why because you always have more to find that you haven’t expressed before. What evades me is the perfect book. I look at what I’ve written and I think that it’s not what I want. It creates a justification for the act of writing for me.

Why do you think people should keep trying to tell stories or write poetry?

I like this question a lot, actually, so I’ll tell you a story. A famous Arabic book, Arabian Nights, tells the story of the king Shahryar. The king, after discovering his wife has been unfaithful, kills her, and kills those whom she had been unfaithful with. He starts to hate women because of it, marrying and killing a wife each day until there are no more candidates. The minister in charge of marrying the king has two daughters, one of whom is trying to get the king to stop killing his brides. She devises a scheme and convinces her father to marry her to the king. She crafts a story of something she continuously works on, and the king decides not to kill her because he is interested in what she’s creating. She tells interesting stories, yet always keeps them incomplete. I think this is about the power of telling stories. They can prevent death or delaying it. We should keep telling stories to overcome our fear of the unknown, or to enrich life, or to discover the deep parts of ourselves. We travel through deep parts of ourselves. It is a way of creating deep connections between cultures. Here, also, is the importance of translation as well as telling stories.

Sophia Maas is the 2021 In Process intern. She is preparing for her graduation while carving out the time to help new writers develop self-confidence, create her own stories, and find inspiration in more experienced writers.

August 11, 2022

Saviors of the Nomadic Spirit

Osama Esber is a Syrian poet, short story writer, photographer and translator who presently lives in California. He is an editor in Salon Syria, Jadaliyya’s Arabic section, and an editor in Status audio magazine. Among his poetry collections are: Screens of History (1994); The Accord of Waves (1995); Repeated Sunrise over Exile (2004); and Where He Doesn’t Live (2006). His short story collections are entitled The Autobiography of Diamonds (1996); Coffee of the Dead (2000); and Rhythms of a Different Time (in process). He has translated into Arabic works by Alan Lightman, Richard Ford, Elizabeth Gilbert, Raymond Carver, Michael Ondaatje, Bertrand Russell, Toni Morrison, Nadine Gordimer, and Noam Chomsky, to name a few. He attended the international writing program in Iowa in 1995.

By Osama Esber

Writing as a creative art, in its essence, is an act of immigration. This is because a creative artist always searches for a new way to express his or her vision in a new form. This act of searching means that the poet migrates from the familiar to the unfamiliar, from tradition to the horizon that his individual talent expands The process of creative artistic experience is defined by this act of migrating.

The manifestos of great literary movements have always endorsed the desertion of outmoded, traditional, and inherited forms, and the pursuit of novel, innovative means of expression. Nevertheless, new creative forms were always received with suspicion; they were censored or burned, rejected or confiscated in a similar manner to how refugees or immigrants were stuck at borders, isolated in ghettoes, looked down upon, or discriminated against.

The great modern cities and civilizations were built by immigrants or by invaders who became settlers after massacring or marginalizing natives. Nonetheless, this act of invasion, of colonization, is not the topic at hand. What I want to emphasize is that the act of immigration inhabits our entire human endeavor and has defined it since the beginning of creation. Even in religion, the first man migrated (as a result of exile) from the heavens, wearing the mask of the fall, or the first sin.

We have been immigrants since our ancient African ancestors decided to find a haven in which humankind could continue to prosper. Modern anthropology, according to Bill Bryson in his book A Short History of Nearly Everything (Broadway Books 2003) was built around the idea that humans emerged from Africa in two waves. Scientists argued that people have long been migrating and sharing genes as well as information. But humans, who are immigrants in the existential sense, have become citizenry with privilege and power, and have given up their previous role as the saviors of migration as a creative option to enrich and prolong human endeavor. To satisfy their egos, they built refugee camps, regarded immigrants as numbers, taxpayers, or voters and created programs for refugees and asylees, funded fences and walls, created humanitarian relief agencies, and became donors or symbols of charity. Power is highly skillful and cunning in crafting and donning masks.

For the current power structures that dominate the world, Africa, the continent from which the first immigrants left, was only a source of slaves and refugees, epidemics and mines; Arab countries are markets and oil wells; Latin American countries are the spring of cheap labor and the dump for industrial waste. Inhabitants of other countries and the children of other cultures were not allowed to taste the bread of modernity, but sometimes were allowed to eat the crumbs that fell from the tables of their supposed masters.

People feed on oblivion and develop a short memory, a memory that betrays history and experience. People forget that they have been immigrants since the first humans migrated to a new place. We live in an age of disconnection and isolation. Politics, as practiced in the world, continue to pave the way for disaster. The gap between misery and privilege expands, technology still under the control of Cain, the slayer of his brother. The story originated and continues from a crime that has disguised itself as progress. Brothers have forgotten that they are related, blinded by greed and the desire to dominate nature.

The human nest, the only haven for us, we the migratory birds of creation, has been disturbed. New developed powers of evil and darkness have been released. The main concern, as usual, has been what should be done to make businesses thrive and large companies continue to operate. We should give money to people so that they can make purchases. The market should not stop. Consumers should remain activated. Concern for the market’s continuous immunity has required taking care of human subjects.

In the Arab world, where the future is as murky as London’s fog, governments behave as if there is no epidemic. Money is not for taking care of people; money is for buying from the West more gears to control people, or for depositing in private Swiss banks.

In the beginning, regimes were relieved by the pandemic. The dark forces of nature were in the service of despotism and autocracy; no one dared to assemble or to go out onto the streets. But as despair continued to reign, and corruption soared to new heights, people challenged the pandemic as well tyranny, and went out to protest because their livelihoods had been stolen and they were deprived of a life with dignity and respect in the miserable cities of the Middle East. These are cities without hope, where one can “show you fear in a handful of dust,” as T.S. Eliot stated in The Waste Land, or in any face. This is not only the fear of losing your job that Eduardo Galeano discussed in his book Upside Down: A Primer For the Looking-Glass World (Metropolitan Books 1998), but also a fear of losing your meaning and purpose, of reaching a point where you find yourself chanting T.S. Eliot’s lines in The Hollow Men, “We are the hollow men/the stuffed men.”

Living in the West is no longer as it was. It may not be as promising as before. It is no longer a rosy dream, contrary to what lines of people at the gates of foreign embassies in the Middle East or at border crossings, or anywhere, think.

Once upon a time, and a good time it was, Arab writers used to visit Western capitals and return to talk about the wonders of modernity, philosophical theories, and great literary and intellectual movements, but now Arab writers come to stay, not to return and tell their stories like the great travelers of old times. They run away from tyranny and bring with them their countries in a metaphoric form, recreate them in language or in dreams, and live in an imagined geography, while in the real geography of isolation they face a double estrangement: They become separate from their roots and victims to a culture of fear, expressed by the established citizenry, who have forgotten their roots, their essence as immigrants who built civilization.

When drought afflicted Syria it led, along with much else, to a tide of uprisings, where the poor and downtrodden went out onto the streets demanding bread, water, and freedom. Now, those who did not die there under bombardment have become immigrants, refugees in neighboring countries where racism bares its teeth. Many of them live forgotten in tents at the borders, while scores of others are under the threat of deportation, which makes evident the narrow limits of human solidarity.

In the light of all this, writers, poets, and artists, the saviors of the nomadic spirit of the human race, should always be ready to forge again- borrowing from James Joyce- in the smithy of their souls the uncreated conscience of their races. They should enlighten their people to the fact that there is only one race on this planet, whose short experience, or journey in a caravan of various magical colors, may come to an end, whose migratory spirit may extinguish and may not find another place to reemerge. It is time to dismantle the barbed wires of our hearts. Climate change and its implicit and explicit dangers should make us think of immigration in a creative way. But the big question is: When our poor planet becomes unable to sustain life, will there be any future anthropologists to discuss another migration?

Cities That Visited Me*

-1-

I saw dolls on your streets

becoming women

and despair stumbling along

like the feet of Syrian workers.

-2-

Sometimes your banks

inject the day’s veins with hope.

Sometimes your dawn

breathes in the smoke of words.

-3-

Your TV channels told us

of other doors,

but when opened,

they only led to another room

in the same house.

– 4-

I saw you a bridge

hanging in the void of your myths

and Mediterranean illusions.

-5-

In your cafes

modernism is smoked

like Cuban cigars,

their leaves smoothed on the thighs

of a professional moment

in a prostitute’s dress.

-6-

I saw books get botox

to seduce their readers.

Your newspapers do not read your mind

your cafes do not change

the wheels or the oil of their language’s engine.

Billboards in your streets wear

naked thighs and bosoms

that relax on sandy beaches.

In their bronze complexion,

we read about a future

that immigrated to other countries.

-7-

The difference in the value of foreign currency

assumes the job of angels

and opens momentarily the doors of paradise.

-8-

I see your face

on an airport’s electric door,

or on a passport stamp,

from which two eyes,

on whose balcony police dogs sit,

look.

-9-

Beirut,

where the borders cross

I saw men made of barbed wire

imprisoning the horizon

inside the pupils of their eyes.

-10-

You are visiting me now,

I wish I could settle you in my language,

I wish I could give you a room

and invite you to a glamorous evening.

I wish I could let you lie naked

on my bed between my arms.

Beirut,

you do not need to forgive me,

I do not fall in love easily with Arab cities,

watching their bellies dancing

with the belt

of death, poverty, tents, and slums

wrapped around their naked waists

does not excite me.

The clock lost its handles.

It looks featureless,

like your soul,

it has lost the road to a body.

* From a divan in process with the same title.

August 11, 2022