Julian Wasser, the ‘Photographer Laureate’ of L.A., Dies at 89

In the 1960s and ’70s, he created indelible images of the city’s combustible mix of art, rock ’n’ roll, new Hollywood and social ferment.

By Penelope Green | Feb. 14, 2023

Julian Wasser, the artful and rakish photojournalist who chronicled the celebrity culture of Los Angeles that began percolating in the 1960s — a heady, sexy and often combustible brew of new Hollywood, art and rock ’n’ roll — as well as the city’s darker moments, creating some of the most indelible images of that era, died on Feb. 8 in Los Angeles. He was 89.

His daughter, Alexi Celine Wasser, said his death, in a hospice facility, followed a couple of strokes he suffered in September.

When the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at a civil rights rally in Los Angeles in 1963, Mr. Wasser was there. When the Watts neighborhood erupted in riots in 1965 after a Black man there was brutalized by the police, Mr. Wasser captured the agony of a city at war with itself.

And when Robert F. Kennedy addressed his supporters at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles in 1968, after winning presidential primaries in California and South Dakota, Mr. Wasser photographed the joyful young senator, just moments before his assassination.

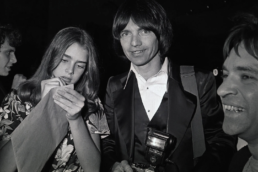

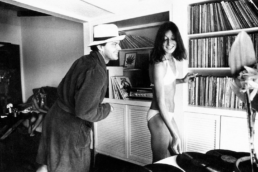

Yet Mr. Wasser was perhaps better known for chronicling L.A.’s counterculture and its outsize bohemian characters: He shot a bikini-clad Anjelica Huston and Jack Nicholson horsing around in a living room; Steve McQueen on a movie set, exhaling a plume of smoke and exuding a glacial cool; and countless scenes from the Whiskey a Go Go, the hot nightclub on Sunset Boulevard.

Mr. Wasser was also the perpetrator of “that photo” of Eve Babitz, the late author and sensualist, then age 20, naked and playing chess with the artist Marcel Duchamp, a stunt hatched during the artist’s retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1963. The museum’s director, Walter Hopps, happened to be Ms. Babitz’s (married) boyfriend.

Stories, and memories, have varied over the years, but as Ms. Babitz told it, the photograph was an attempt to annoy Mr. Hopps, who took his wife instead of Ms. Babitz to the exhibition’s opening.

Mr. Wasser said that the composition was his idea. “I had always wanted to see Eve naked,” he said in an interview with The New York Times for her obituary in 2021, “and I knew it would blow Marcel’s mind.”

The black-and-white image became so famous it showed up in a poster for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The art critic Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp’s biographer, called it “an erotic and very Californian footnote to Walter Hopps’s historic show.”

James Danziger, one of Mr. Wasser’s gallerists, said Mr. Wasser had “brought an artist’s eye” to his photojournalism.

“You could call it the auteur theory of photography,” Mr. Danziger said. “You let things happen, but if it made for a better picture, you weren’t afraid to direct the scene.”

And then there were the photographs of Joan Didion, commissioned by Time Inc. in 1968, shortly after her essay collection “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” appeared. There is Ms. Didion, steady eyed and brandishing a cigarette, in a variety of poses with her Corvette Stingray, potent images now etched into the collective consciousness.

The pictures appeared on Ms. Didion’s books, were recreated by the fashion company Celine in a homage to the author featuring the model Daria Werbowy, and were the subject of a 2015 show at Mr. Danziger’s gallery in Manhattan. They could even be spotted on tote bags, as Ms. Didion’s nephew Griffin Dunne did on the subway on his way to her memorial, sported by young women who were also en route to the service, Didion groupies with literary swag.

When Mr. Dunne interviewed Mr. Wasser for his 2017 documentary, “Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold,” Mr. Wasser recalled how he had shot only two rolls of film that day.

“He knew he got it right away,” Mr. Dunne said. What he did not anticipate, he added, was how people would react to the photos. “He never dreamed they would be on tote bags, as iconic as a Che Guevara T-shirt,” he said.

With his shaggy hair, leather jacket and holster of beepers and police scanners, an assortment of cameras and press badges slung around his neck, Mr. Wasser was quite a presence himself, said Craig Krull, a gallerist who represented him for the last 30 years. “He had an unflinching eye for the intensity of experience in L.A.,” Mr. Krull said, “whether it’s a club on Sunset Strip or the Manson murders or the Watts riots.”

Mark Rozzo, whose 2022 book, “Everybody Thought We Were Crazy: Dennis Hopper, Brooke Hayward and 1960s Los Angeles,” covers much of the territory that Mr. Wasser did and used one of his photos — of Ms. Hayward and Mr. Hopper looking especially mod and particularly glum — said that Mr. Wasser was “perhaps the closest thing that Los Angeles has had to a photographer laureate.”

At least for his rollicking moment. “This was the period of Didion writing in The Saturday Evening Post and Ed Ruscha’s street-inspired pop art and Brian Wilson’s teenage symphonies to God,” Mr. Rozzo said. “Julian was right in the center of it all, and he made sure he was at the center.”

Julian Wolf Wasser was born on April 26, 1933, in Bryn Mawr, Pa., the only child of Leo and Frances (Rothman) Wasser. His father was a lawyer, his mother a schoolteacher. He grew up in the Bronx and Washington, D.C.

A teenage news junkie, Julian cut school and sneaked out of his room at night in imitation of his hero, Arthur Fellig, the photographer better known as Weegee, to chase down crime scenes with a police scanner and submit the photographs to newspapers, which inevitably published them.

“Every night I would climb out my bedroom window and steal my father’s car when I was 12 and take pictures, and they’d be on the front page of The Washington Post,” Mr. Wasser told a television reporter in 2019. “My father would say, ‘Look, there’s another Julian Wasser in Washington.’ I said, ‘Yeah, Dad.’”

He worked as a copy boy for The Associated Press in Washington and, by his account, was able to meet Weegee and accompany him to crime scenes when the photographer visited Washington.

His daughter said that as a child she was often deputized as her father’s assistant. She monitored his ever-crackling police scanner: “Daddy, the night stalker is being arrested!” (She was 4 years old at the time.)

When Will Smith married Sheree Zampino, his first wife, the Wassers crashed the wedding. Alexi Wasser, then 11, was armed with a disposable camera, which she was savvy enough to stash under her shirt when security arrived to remove the unauthorized photo team. She recalled her father saying with a straight face, “I’ve never seen that kid before.”

“It was all very absurd and ridiculous,” she said. “Later Julian told me my photographs ran in whatever tabloid he was shooting for, but he stole my credit line. Our relationship had a very Ryan and Tatum O’Neal ‘Paper Moon’-esque quality.”

In addition to his daughter, Mr. Wasser is survived by a son, James.

In 2014, Mr. Wasser published a photographic memoir, “The Way We Were,” more than 170 pages of his greatest hits, and then some.

“The effect of so many otherworldly behind-the-scenes pictures plays out like a kind of movie in itself,” Rebecca Bengal wrote in the New York Times magazine T. “As Wasser captures them, in grainy close-ups and candids, the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s marked a time of unusual access: carefree, hair-let-down moments and stars mingling with real people.”

“It wasn’t like it is now,” Mr. Wasser told The Guardian in 2014. “There were no paparazzi, no VIP sections, no security. It was a really innocent time. You’d just walk up and there they were. They’d stop and smile and pose.

“Now it’s a business,” he continued. “If you want exclusive access to a celebrity, you have to pay big money. You weren’t considered some sort of psychotic menace who’s going to rob or kill them either. Now they’ll call their security person and you’ll get beat up.”

A correction was made on Feb. 15, 2023: An earlier version of a picture caption with this obituary misstated when the photo of Jack Nicholson and Anjelica Huston was taken. It was 1974, not 1971.