Azzedine Alaïa Has a Different Kind of Show

admin

Mirror of: NY Times By: Vanessa Friedman

Forget frocks and eye-popping knitwear. Think poetry, with a dash of politics on top.

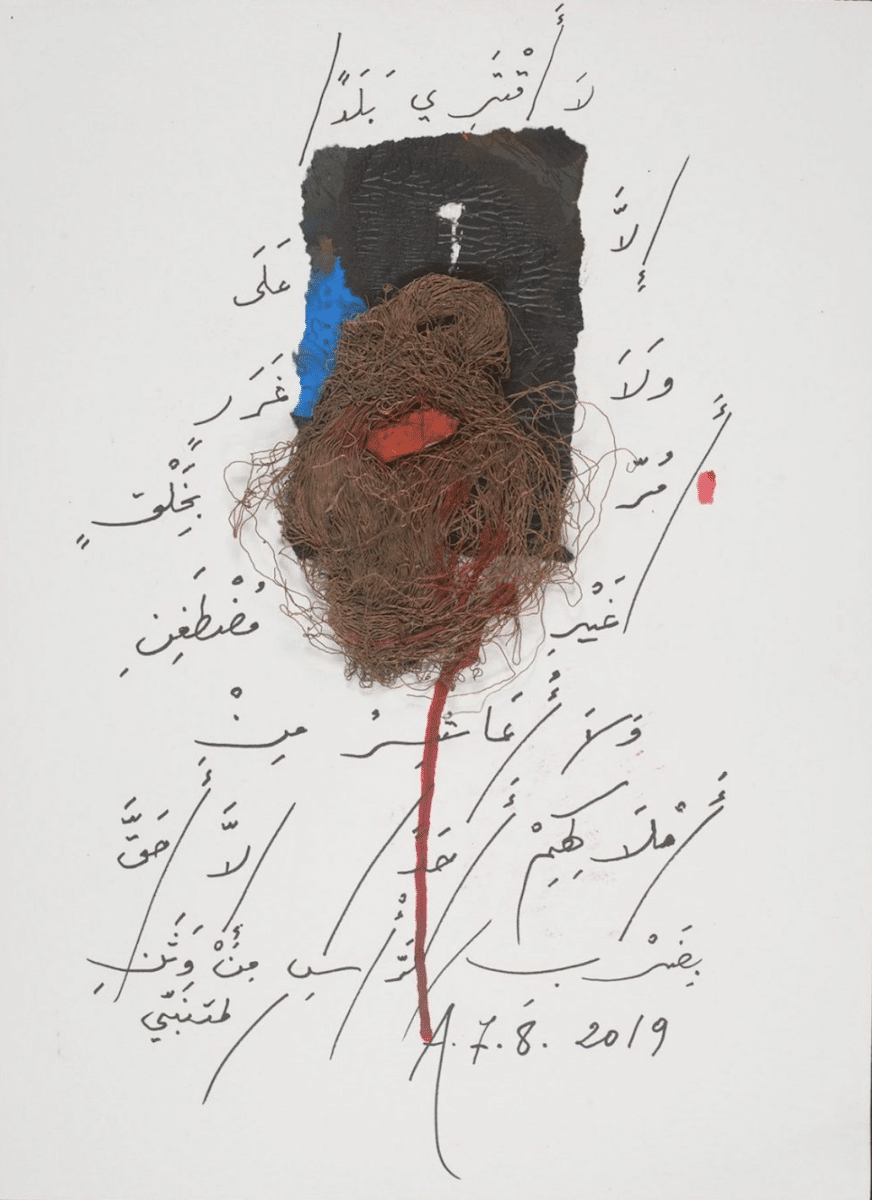

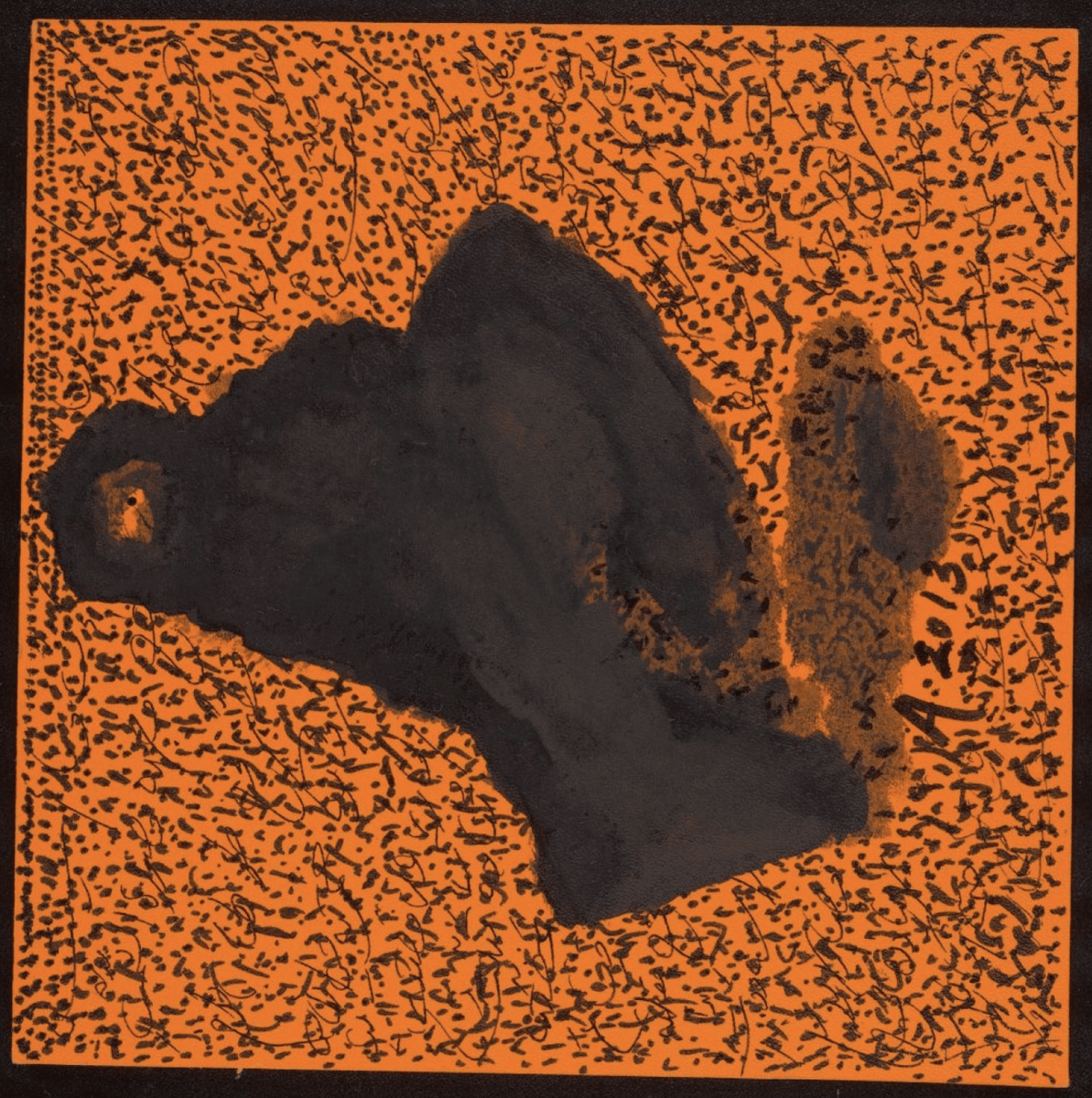

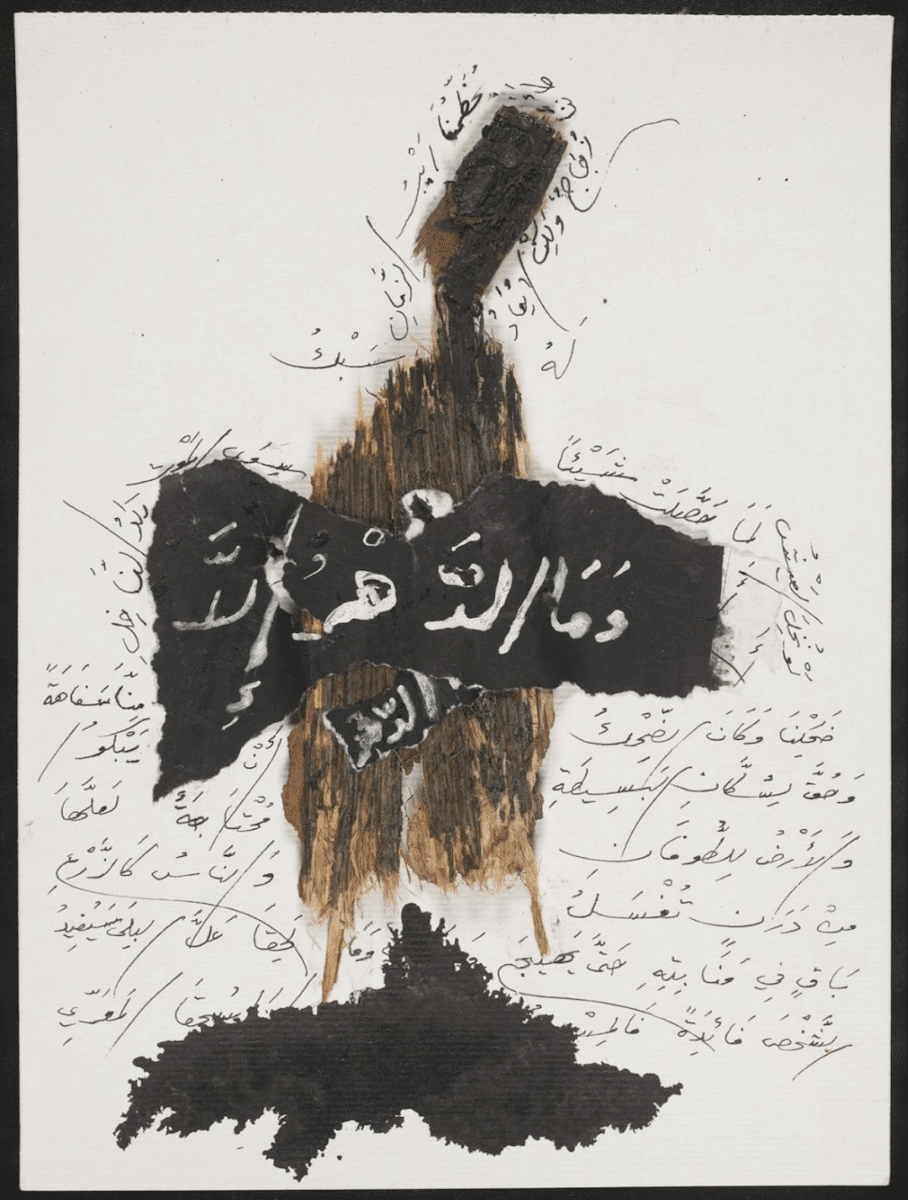

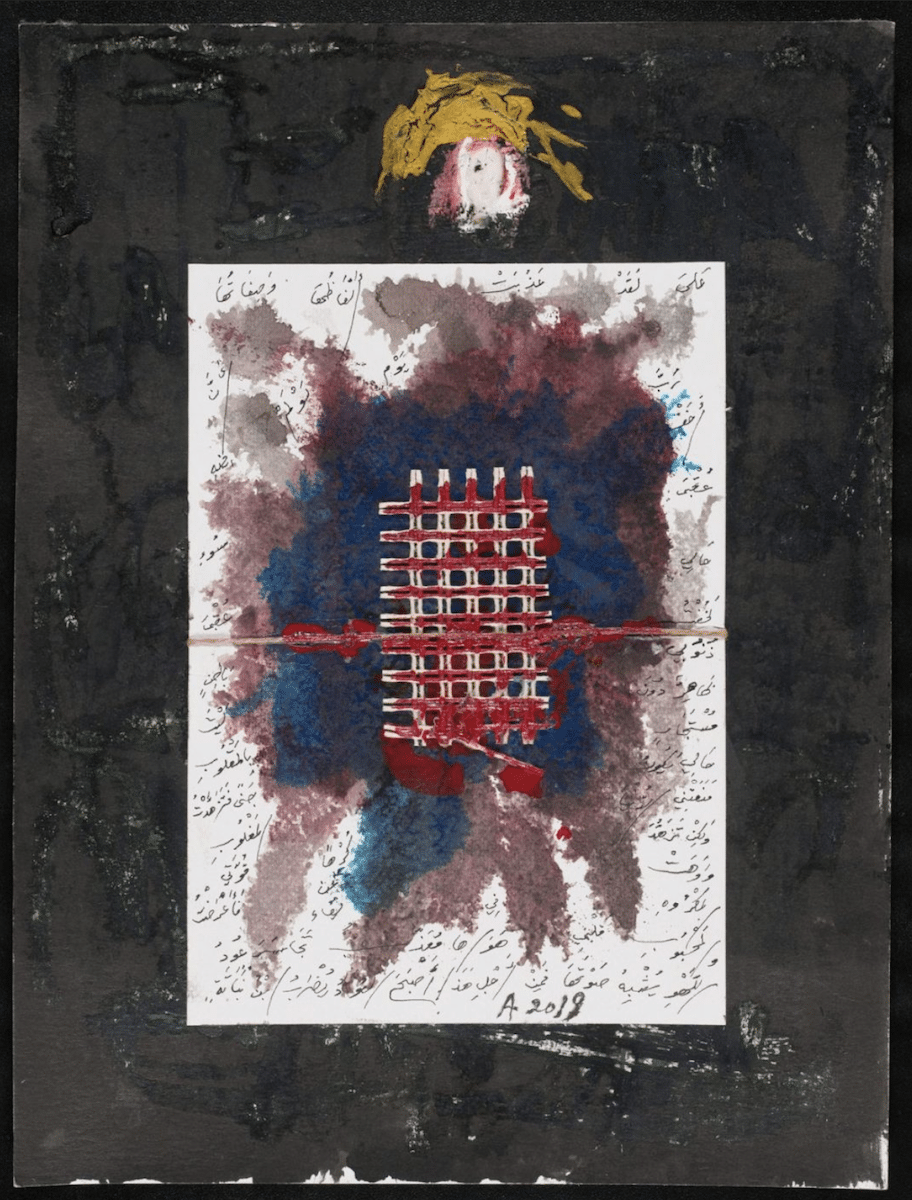

In a move to reinforce the idea of creative community, the designer Azzedine Alaïa has transformed his Paris showroom, most recently host to three days of fall/winter défilés, into a gallery space devoted to the exhibition of more than 70 collages by the Syrian-born, Paris-based poet Adonis, one of the most famous of the Arabic world and often named as a contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature. On Monday, Adonis was awarded the Kumaran Asan World Prize for poetry.

The show, which will run until May 10 and is the first time that many of Adonis’s collages have been publicly displayed, is the most ambitious cultural effort yet from the designer. (He also hosts the annual World Press Photo exhibit, as well as other, less formal essayages.) It also signals the beginning of what are planned twice-yearly, free-to-the-public exhibits in Mr. Alaïa’s atelier/flagship store/home base in the Marais section of Paris.

A catalog of the Adonis works will also appear.

Though fashion in general is having something of a public art moment, what with the Frank Gehry-designed Fondation Louis Vuitton and the Prada contemporary art museum set to open in Milan, Mr. Alaïa’s effort is the smaller, more personal version of the trend.

Mr. Alaïa decided to hold the Adonis exhibition, for example, after the poet gave him one of his collages, which involve superimposing words — his own and those of other Arabic poets — and scraps of material over a background of “invented” calligraphy, after a visit. (The trip presumably included a meal in the Alaïa kitchen, as most do.)

“Do you have any more?” Mr. Alaïa asked. It turned out Adonis did — when he was having trouble writing poetry, he would make some art — so they hatched a plan: not just to display a previously unknown side of the writer to the world, but to hold an event that would show, not tell, visitors a different side of the Arabic world than the one in the news.

In other words, the messaging opportunities woven into the exhibit escaped no one. Well, Mr. Alaïa is known for his uncanny ability with a knit.

INTERVIEW // A Wandering Light in the Universe: A Conversation with Adonis

admin

Adonis, born Ali Ahmad Said Esber in al-Qassabin (Syria) in 1930, is a poet, writer and visual artist. Adonis was exiled to Beirut in 1956 and moved to Paris in 1985, where he is still based. In addition to his poetry, for which he was awarded the Goethe Prize in 2011 amongst others, Adonis has written about literature and art and continues to be a critical voice in magazines and newspapers on political and social affairs. Since the 1990s, Adonis has been creating visual works of art with found materials which he has exhibited worldwide. In conversation with Immediations editors Ambra D’Antone and Erica Payet, Adonis discusses the different dimensions of his visual practice.

Adonis, you have an impressive reputation as a poet, more so than as a visual artist. In previous interviews, any mention of your visual works is always attached to larger discussions about your poetry. Nevertheless, when reading your poetry and looking at your works we can see immediately that you try to break the ideological boundaries between the two, so that artist and poet are no longer distinct identities. In keeping our focus on your visual works in our discussion today, we wish to bring out this aspect of your work and to have a larger understanding of your artistic practice. Let us start by directly addressing the objects.

I have to say from the beginning that I don’t have a background in painting, properly speaking, or in sculpture. I don’t come from that tradition. It is true that I have met many artists and sculptors, and that I have written extensively about them, especially but not exclusively Arab artists. But I come at it from a different angle, from the angle of poetic vision. I believe that to be a poet means to experience the world wholly, as a totality. Everything is poetry. Even the peasant is a poet: he works in his garden, he works in the fields and changes them. There is change and there is reconstruction—within this cycle, everything is poetry. Everything, even love…all of it. I wanted to widen the frontiers and the space of the written poem. For that reason, I have tried to create poems with ink, lines and stains…just like this. They are extensions of my poetry and they themselves are poems, written in a different manner. Every poem, every work has its own personality, its way of being.

When did you start making them?

I started a little over twenty years ago, by accident. I said to myself, you know quite a few painters and sculptors and you’ve written about them—sometimes one gets fed up of writing and reading—so I told myself why not try making something, giving your hands away to the ink and finally liberating them? And I did try. I made visual works for around a year, but when I looked at them, I did not like them, and I destroyed them. Then I started again, but this time it seems I did something different. One day my friend Michel Camus, the French poet, came to my studio and saw what I had done, these little things, and asked me who the artist was. I told him “It’s a friend of mine” (he laughs), I did not have the guts to tell him it was me! He said that he’d love to meet that friend, so I told him that I would arrange a meeting for the following week, in my studio. Michel showed up a week later; we sat down and chatted about various things for a while. About twenty minutes later, he finally asked: “So, where is your friend?” Only then did I muster the courage to tell him that I was the artist! He was very happy, he said he loved the works and suggested I exhibit them. Here, that’s how I gained some confidence in my practice and decided to carry on with it. Ever since that, many people have liked what I do and I have held some big exhibitions, for me they are immense! I have a big show planned in Hangzhou, in China, opening November 1st; I have already exhibited in China three times, but I have also shown the works in Paris and London…so you see, I am in demand! That’s how I carry on with it.

What type of subjects do you wish to represent?

Just like in my poetry, I want to represent simultaneously the small, mundane things of everyday life, as well as the farthest, most obscure metaphysical truths, the totality of the cosmos. These are my subjects, because I am not an ideological man and I feel like I have been thrown into this universe. I don’t concern myself with hard-core politics, with regimes and ideology, my works are not about that. I question beauty, love, the meaning of life, the future, the poverty that is so widespread in the world. Why is there poverty, in a world so rich and varied?

You prefer to call your works raqīma (رقيمة), rather than collages. Why?

That’s it, raqīma. We constantly have to create. I come from an Arab culture, and in Arabic the word collage has a bit of a negative connotation. But there is a word, raqama or raqana, which designates both the ink and the form, the line. So, I thought, I ought to invent a new word, raqīma, instead of saying collage.

Can you say a bit more about the importance of materiality and of technique for the raqīma? Where do you find the materials for the works?

It is just like the words in a poem. There are specific words that signify material things, and a poem is made up of different words, from God to a pebble. So, you see, my material can be everything. Anything I see, no matter what, plays a part in the symphony of the work. Everything, without exception. That’s why I find my materials in the streets. Once somebody saw me, while I was picking up something from a curb to use in my works, and the way he looked at me, I am sure he must have thought “This guy is crazy”! (he laughs). You see, it is like giving meaning to the insignificant.

You have said before that you have “a problem with painting, with colour”, and that you prefer using ink.1 In the Fifties and Sixties, some artists rejected artificial paint, inspired by prehistory or pursuing a political statement. Do you establish a dialogue with these practices?

This is really personal. Using ink gives me more freedom than traditional colours, but I know this is relative. Maybe one day, if I ever have a big studio, I could master colour, create my own. Maybe then I could change. You see, everything is open for me, everything is possible—even the impossible. Ink is easier, I have control over it. I always like being at the core of my materials: I like to change them, break them, turn them around, make new forms from what is in front of me. Ink allows me to do that easily. Yet, I do hope one day to be able to do that with paint. I did try, in four works. A friend of mine, a painter, came to me and I told him how much I’d love experimenting with paint.2 He encouraged me, and I produced four canvases. He liked them and he plans to exhibit them in Venice! Those canvases are my first works not on paper. There have been many interesting experiences with paint in the past, there were many artists that used a variety of materials even without paint. Whether I am in dialogue with them depends—in the last analysis, the work of art for me is form, not an idea. The essential moment is the creation of new form, and the idea will follow. This is not easy. But this means that the artwork is open to every possibility, to every materiality. I can say this for sure: there are no limitations, and if there were there would be no art at all. The creation of art necessarily exceeds the boundaries placed on form.

The medium of raqīma also seems to allow for a reflection between existence and non-existence. You reflect a lot on the idea of the fragment, for instance. Is this conscious?

You see, a work of art is important only insofar as it opens itself up to a myriad of interpretations. Its wealth resides in that. When the meaning of an artwork is hard to pin down, that work is like an aperture onto infinity. That’s why the Old Masters are still talking to us. Michelangelo is here right now; he is drinking Perrier with us! (he laughs)

In the past, you have talked about the hand as being a privileged tool that is rarely subjected to mental censorship. Can you elaborate?

When I say this, I have a particular focus on Arab civilisation and the history of the Arab world, but I think it equally applies to other peoples and other histories. There is a perennial preoccupation with and interest in the mind and what it does: the creation of language, culture, imagination etc. But we always forget about the hands. Think about it: hands are a thing of genius! That’s because they have no reins. The head is constricted by rational rules and limitations. While the head thinks, the hands play, and they are the absolute players. Art is the great game, in the positive sense, and God, who has created this world that is so varied and infinitely complex (but you can believe whatever you want), is the greatest player of all. So, I think, we need to free our hands. The artist, especially, plays with the hands: the coincidences and chance encounters between form and colour cannot happen but with the hands, because the head is always busy thinking, being rational! Hands are not enmeshed in calculations, and that’s why they matter. Though, this has been neglected by the public and by historians: have you read a single book about the history of hands in England? In Islam, hands have accomplished wondrous and beautiful things—not the head. There are hand-woven carpets that are worth thousands of books! That’s why I believe we have to care for the hands and set their genius free. Unfortunately, in order to do that I have had to do things that I did not have control over. Because yes, we want freedom, but that comes at a cost. We cannot be free in a cage, in a prison, or a restrictive tradition. There are conditions.

In your raqīma the written language plays a crucial visual function, almost like an outpouring of poetry into the visual domain, or a translation of one medium into the other. How do you understand this relationship?

Writing, in the sense of a sentence written on a visual work and its semantics, for me has nothing to do with form. Writing, just like a background, like a line, plays an integral and essential role in the artwork. It absolutely cannot be reduced to an illustration, an accompaniment. Form and writing are not separate, no. They are a whole. That’s why I occasionally use a pseudo-script, an imitation of language: I do not wish to create a writing and a work, but a work made of words, of lines and of ink. It is not a process of addition, but a totality.

Can you talk a bit about the poetry fragments that you choose for your works?

In principle, I like to celebrate the great Arab poets of the past. Poetry is very marginalised in Arab society, although Arabs have created nothing but poetry! It is their single greatest creation. Despite that, it is not well known, and it is disregarded. That is why I like to celebrate those poets—everything I write is meant to pay homage to them and to poetry.

Your work speaks in and of different languages: Arabic, your native language and the language you write in; French; the language of poetry; the visual language; the language of political criticism. What is the language you feel best conveys what you want to say?

Fortunately, or maybe unfortunately, we only have one mother. Maybe we have more than one father, though…you never know! (he laughs). But one mother only. The language of creation is the mother tongue. My mother tongue is Arabic, so I write and create in Arabic. Additionally, there are languages of culture, that I like to call the father-tongues. My father-tongue is French.

You were one of the founders of the journal Shi’r together with Yusuf al-Khal, amongst others. The journal was a fierce advocate of translation. What are your opinions on translation? Not just as a literary act, but also as cultural and possibly artistic transmission.

The issue around translation is really complicated, and on top of that we can never reach a consensus. Translators and writers are always criticising each other’s translations! Once a friend of mine who is Russian told me “I beg you, Adonis. Do not read Pushkin in French, because rather than translations those are deformations!” I asked other friends of mine who are French, and they liked the French translations! My beloved friend Yves Bonnefoy, who has unfortunately passed away, translated Shakespeare. I could never find any English speaker who could criticise his translations! But, instead of admitting that Yves Bonnefoy has given Shakespeare a new dimension in French, we always criticise his way of translating and of rendering the original words. Translation is a space of conflict. Although, despite that, I firmly believe that our future culture will be founded on translation, or it will not exist at all. For me, the importance of translation is beyond discussion. We live in a multi-cultural and -linguistically plural environment; without translation there will be no future, because the future is translation. New generations will have to speak different languages, because only one language is absolute poverty—it cannot work! At the same time, translating a philosophy book and a poetry collection are different things, and when we get to the nitty gritty details my opinion is based on my personal experience. First, I believe that in order to translate poetry it is necessary to be deeply aware of what poetry is, it is necessary to know the poet and his language, more than one’s own mother-tongue. The mother-tongue receives the other, and so must be intimately acquainted with it. Secondly, we cannot translate literally. There can never be any word-to-word correspondence from one language to another, never. Because words in a poem don’t come from a dictionary, but from their context, from their relationship with the words before and after, as well as from its role within the imagination. Translating a poem means translating its imagery, not its words. So, you see, translation is a very complicated matter and we are never in agreement. Thankfully!

And speaking of translation—can you tell us about your experiences exhibiting your visual work to the public in Paris, London and China? Were those experiences different from each other?

The Chinese are more open, more understanding and disinterested in the art market that dominates Europe. I have sold many works in China, but only to intellectuals and such people. I think I am better understood in China than in Europe, although there are individuals in Europe—but it is a handful of people—who understand my works and my poetry.

In terms of being understood and communicating with an audience, is writing poetry for you different than making visual works?

Firstly, a poet never writes for others. The other always comes after. Look at this audience here: how can a poet write for them? It is ideological, it kills poetry. Everything that is common is anti-poetic. You see, when these people enter a gallery and look at artworks, they all formulate different opinions. Writing for the people is nonsense. And we must also ask: who are the people? The peasant? The workers, or the bourgeois? The soldiers? The regime? The absurdity of these questions demonstrates that these are nonsensical words, they are ideological and political. The poet wants nothing to do with that. Firstly, I write to understand myself better. Who am I? Secondly, I write to understand the other better. And thirdly, to understand the world better. To gain a better understanding of all three, in my writing I establish a meeting point with what we call the reader. The work of art is a space of confluence; there is no single message because there are many messages. The way Michelangelo speaks to us today is necessarily different from how he spoke to his contemporaries. So, we write to make the world more beautiful and more open, beyond all ideology. Ideology is a veil covering not just the face but covering truth and, ultimately, the world.

Does this apply to your visual works as well?

Yes, absolutely. They are also poems.

Let’s talk about your life away from Syria. You once said that exile is an internal condition rather than a geographical one.3 Can you elaborate on this?

The way I see it, we are all thrown into exile. It is true that we are born free, but that has nothing to do with real freedom. I was born, I came to this world free, but at the same time I was placed in exile. The human being enters at birth a state of exile. This essential and existential exile is a product of the ambiguities of the world we live in. Why live? Why die? Why live, if only to die? If we only live to die, why be born at all? So, you see, the problem goes deeper than ideology and faith. Religious faith is appealing to people, because they no longer have to think or to search or to struggle. They follow a ritual, and that calms them down. But for those who constantly question the human nature and the world, who question the beginning and the future, the finite and the infinite, there is no answer. For them the world is a constant search, so they are always exiled. Even when I am writing, I can never fully express myself—I am exiled within language. Today I am not who I was yesterday, I have changed. There is no place where man stays the same throughout his life. The condition of exile has nothing to do with geography; it is an internal, a human condition.

So, do you feel Syrian, or French? Or neither?

That is not a concern for me. What engages me and preoccupies me constantly is the earth, the soil where I first set foot. I love to see it, but I would never live there. Maybe it is psychological—I like to see who I was and, by contrast, who I have become. It is very personal. My country is these two or three meters where my feet touched the earth for the first time.

Let’s talk about regionalism: for example, Turkey and Syria are neighbouring countries, and have a shared Ottoman past. Modern artists had similar concerns and strategies in Turkey and Syria. Yet nowadays they are considered separate regions, ethnicities, cultures. What do you think about this? Are identities so separate, or was there some hybridity and cross-cultural transmission, historically?

This is complicated. Turkey for me represented hope, a hope founded on Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and his reforms. A country based on secularity. It is hard for me to think about Turkey in other terms. Let us give the people who believe in God the freedom to pray as they wish. But the state, the law, the institutions, education…everything must be secular. I think this must apply for Syria and the Arab world as well. Without a clear separation of state and religion, there cannot be anything but decadence. And not just decadence—decay and the ultimate end! I do not envision a real human future for the Islamic world—Turkey, Syria, Egypt, etc.—without a radical separation of religious and secular powers. Otherwise it is a catastrophe!

The modernist Syrian artist Fateh al-Moudarres (1922-1999) once said, that “the artist is a witness of their time.” What are your opinions on this?

That makes sense. I would add that there are artists, poets and creative individuals who are part of history, but there are others who create history. History plays a part in their creative act. Everything that is institutional, political or social is bound to fade. The great kings and leaders of the world, the great political figures, they are all gone. But never Michelangelo or the great painters, who are always there. Never the great poets, who are always there. They weave history in their production—not just as witnesses, but as active creators. That is why it is in art that peoples and nations find their identity.

So, what role do your works play in history?

I do not know! This is not for me to say, only the future will determine it! (he laughs).

In the 90s you wrote a book linking Sufism to Surrealism. For some, this might be a contentious pairing—especially given the anti-religious attitude of Parisian Surrealists. Can you explain how you understand the relationship between the two?

Sufism, or mysticism, is crucially misunderstood. Sufism and the Sufis, whom we call Islamic mystics, have nothing to do with official Islam. In fact, they have completely changed the conception of God in Islam. In Islam, God is a force ruling the world but outside of it, detached, much like in the Bible. For the mystic, God manifests himself immanently in the universe, and the universe is part of him—destroying the notion of God in Islam. How then can we call them “Muslims”? Secondly, the mystics have also changed the concept of identity, from one of heritage to one of creation: being born a Muslim does not mean that you will remain a Muslim. We do not inherit our identity in the same manner we may inherit a plot of land, or a house. The human being creates his identity, in creating his oeuvre. Thirdly, they have changed our understanding of the other: in Islam the other is always a renegade, either a Muslim or a social reject. The mystics have reinforced equality amongst men. The I does not exist without the other, and in order to find myself I have to go through the other. The other is a constitutive element of the self. So, it must be clear that the mystics have subverted Islam completely, which is why Islam has forsaken them. The people here, the orientalists and their students, do not understand this. Think of the condition of being a woman in Islam: for the mystics, the feminine constitutes the origin of the world, against the official tenets of Islam. Moreover, the mystics have invented the practice of writing by dictation—a dictation which comes from beyond, like automatic writing. I have told poets, especially Arab poets to read the mystics before reading Surrealist texts and being influenced by them. But they do not want to understand that it is a mysticism without religion! Sufism is a Surrealism avant la lettre, as well as essentially an anti-Islam mysticism.

You have said that Arab poets of the past like Abu Nūwas (756-814 AD), Al-Niffari (10th century) and Al-Maʿarri (972-1057 AD) invented al-imlaʾ, the technique of writing by dictation, a sort of automatic writing like that which the Parisian surrealists used in the 1920s. Do you see the Arab poets as precursors of Surrealism?

I do not say that, but after reading the mystics and the Surrealists I do make note of the fact that there is a Surrealism avant la lettre. I have signalled this connection in my book Sufism and Surrealism. Though, people still do not understand that I am talking about a mysticism without religion and they criticise me, even if it is written on the first page!

In your book Le Diwan de la Poésie Arabe Classique (2008), you talk about reading the poetry of Abu Nuwas and al-Niffari and truly understanding it as revolutionary after having connected with Surrealism. What do you mean by this?

Yes, I do think that. In order to become acquainted with Surrealism and to be inspired by it, I think that an Arab poet should read what is available in his or her language, rather than a (contested) translation of Parisian Surrealist texts. Read what you have in your tradition! But they do not read it, they are completely mesmerised by the other. And by the way: Surrealism has been a great source of conceptual and visual inspiration, but it has never created a great poet. All the great poets that had encounters with Surrealism, eventually left it: René Char, Yves Bonnefoy, Paul Éluard, Louis Aragon…André Breton was an extraordinary theorist, a great character whom I admire as a prose writer—I am thinking of Nadja, for example. But he was not a great poet! (he laughs). Unfortunately, I did not have a chance to meet him, but I did meet Aragon in his last days, and Tristan Tzara too… Surrealism has caused an incredible and necessary shock to society, creating painters and theorists, but there is no great poet we can call Surrealist. Al-Niffari was the greatest Surrealist that ever existed!4 But this a contestable statement, because there are always imperialist considerations, and moreover everything that emerges from the Islamic world is immediately labelled as religious. Yet, we cannot identify everything as religious. There are and have been many who were born Muslim but are not Muslim, neither in practice nor faith. Abu Nuwas was a Muslim, for instance!5 Unfortunately, people tend to generalise. Never, in writing poetry or otherwise in creating art, must we accept things for what they only seem to be. This is complicated.

Were Surrealist texts available to you in Syria in your youth?

My French was poor, I could not have understood them. But I did read some when I came to Paris. The majority of my friends were Surrealists. The last great Surrealist that existed was a good friend of mine and wrote a lot about me and my works—Alain Jouffroy. He wrote a very good article about me in a catalogue for the Institut du Monde Arabe. And so, I was on the side of the Surrealists: I was their friend, but only to better understand the relationship between East and West, only as a Muslim. But the term “Muslim” has infinite variations. We tend to mask or even erase this variety, because it is difficult to find. Simplification kills it and renders everything banal.

Would you say that what people like the Syrian poet Orkhan Mīassar (1911-1965), Syrian painter ʿAdnān Mīassar (1921-1979) and Fāteh al-Moudarres were doing in the 40s and 50s in art and poetry—would you call that a Syrian, or Aleppine, Surrealism?

Yes. They were influenced both by Surrealism and by Sigmund Freud. Freud was particularly important for Orkhan, who was a great friend of mine. Unfortunately, this was a unique case. In Egypt Surrealism enjoyed more popularity. You know, to master the body the Surrealists resorted to mescaline and drugs, like Henri Michaux—to the artificial. They resorted to the artificial to arrive at the natural. This is contradictory. The Sufi, the mystic mastered his body naturally to arrive at the supra-natural. That is Surrealism. The Sufi never resorted to drugs and reached a complete mastery over his body, becoming a wandering light in the universe. We also have to discuss the importance of femininity both for mysticism and Surrealism. The feminine is the source of existence, in it resides the essential core of this world. To quote the Sufi mystic Ibn ‘Arabi, Kullu makānan lā iuʾannathu, lā iu’awwalu ‘aleihu, “consider worthless anything that does not feminise.”6

What does it mean to you to be making art today, as a Syrian? Do you think art, and your art, has a role to play in the context of war and violence?

We would have to talk about this extensively, about what it means to create in Syria right now. But let me ask, what is the difference between creating now and before? It is a matter of degree, rather than ontological. You cannot create in a society founded on religious beliefs—there cannot be any creation, only repetition. We must understand that, so that instead of supporting fundamentalism, the Muslim Brotherhood, the terrorists, we can support life and people. It is shocking to see the France of the Revolution supporting Erdoğan or supporting Saudi Arabia in its war against Yemen. I believe that the problem is no longer in the Arab world, it is in Europe. Unfortunately, Europe has become a satellite of the United States, thanks to the influence of Trump, when it should be the opposite. Everything is subverted!

In your interviews this is generally the first question you are asked, so I will finish with it. In Ugaritic mythology, the figure of Adonis signals the cycle of death and rebirth, and was an important symbol for Shi’r. You are still using this name as an artist. Is its symbolic content still important to you?

At the beginning, I never thought about that. I took the name Adonis by chance. But in time, I came to understand that the name freed me, it completely transformed me. I was part of a culture, but thanks to that name I started to break away from it, to be part of another culture. The west was a threshold for me, a completely new horizon. But that happened with time, not at the beginning. It was an absolute metamorphosis. Instead of being a member of a limited civilisation, founded on a religion vision, I became enmeshed in the universe. The universe is my nation.

Julian Wasser, the ‘Photographer Laureate’ of L.A., Dies at 89

admin

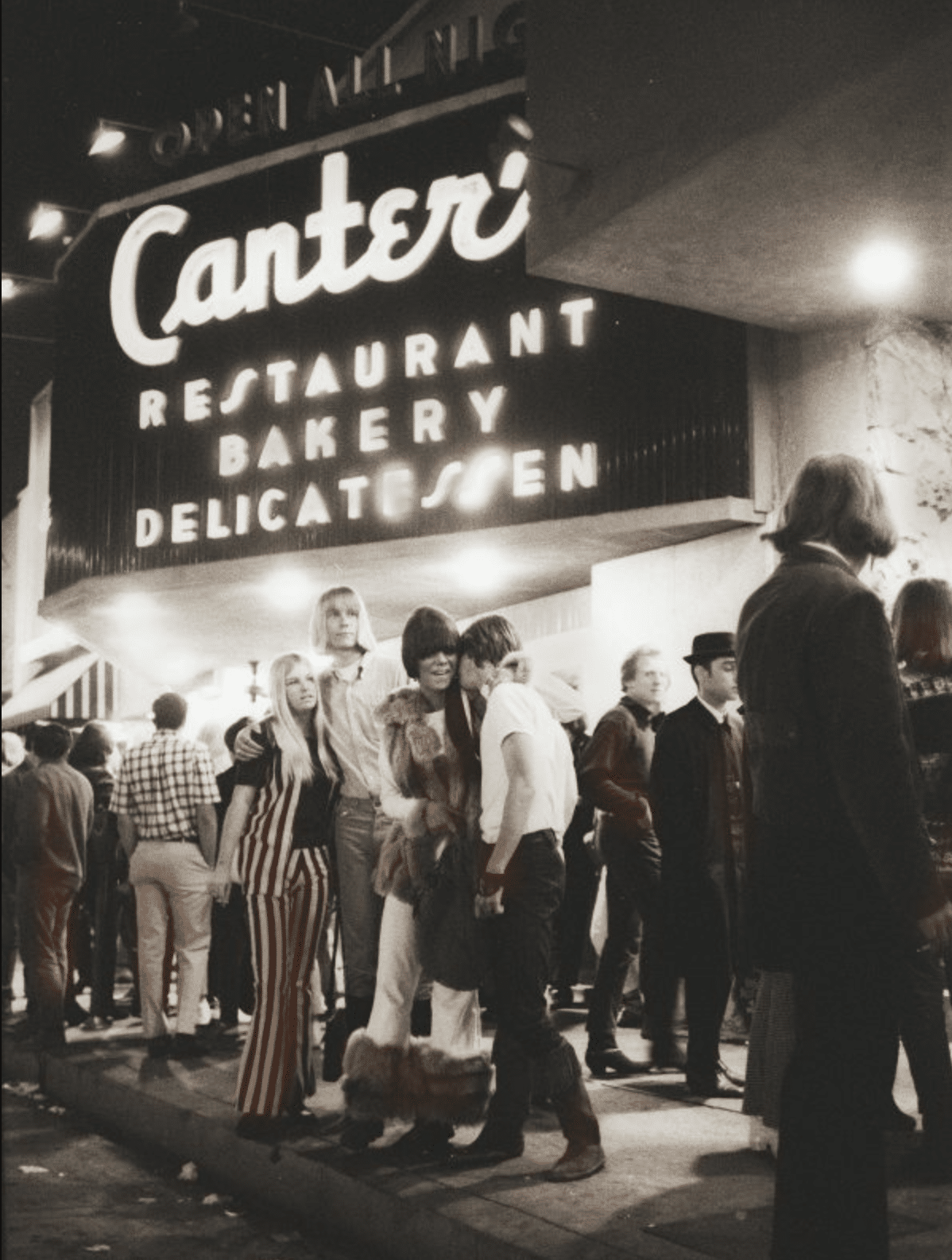

In the 1960s and ’70s, he created indelible images of the city’s combustible mix of art, rock ’n’ roll, new Hollywood and social ferment.

By Penelope Green | Feb. 14, 2023

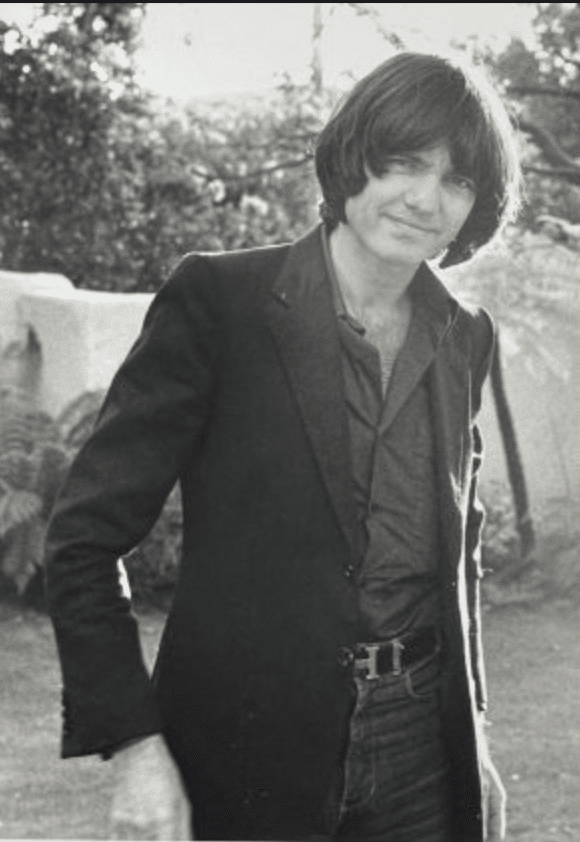

Julian Wasser, the artful and rakish photojournalist who chronicled the celebrity culture of Los Angeles that began percolating in the 1960s — a heady, sexy and often combustible brew of new Hollywood, art and rock ’n’ roll — as well as the city’s darker moments, creating some of the most indelible images of that era, died on Feb. 8 in Los Angeles. He was 89.

His daughter, Alexi Celine Wasser, said his death, in a hospice facility, followed a couple of strokes he suffered in September.

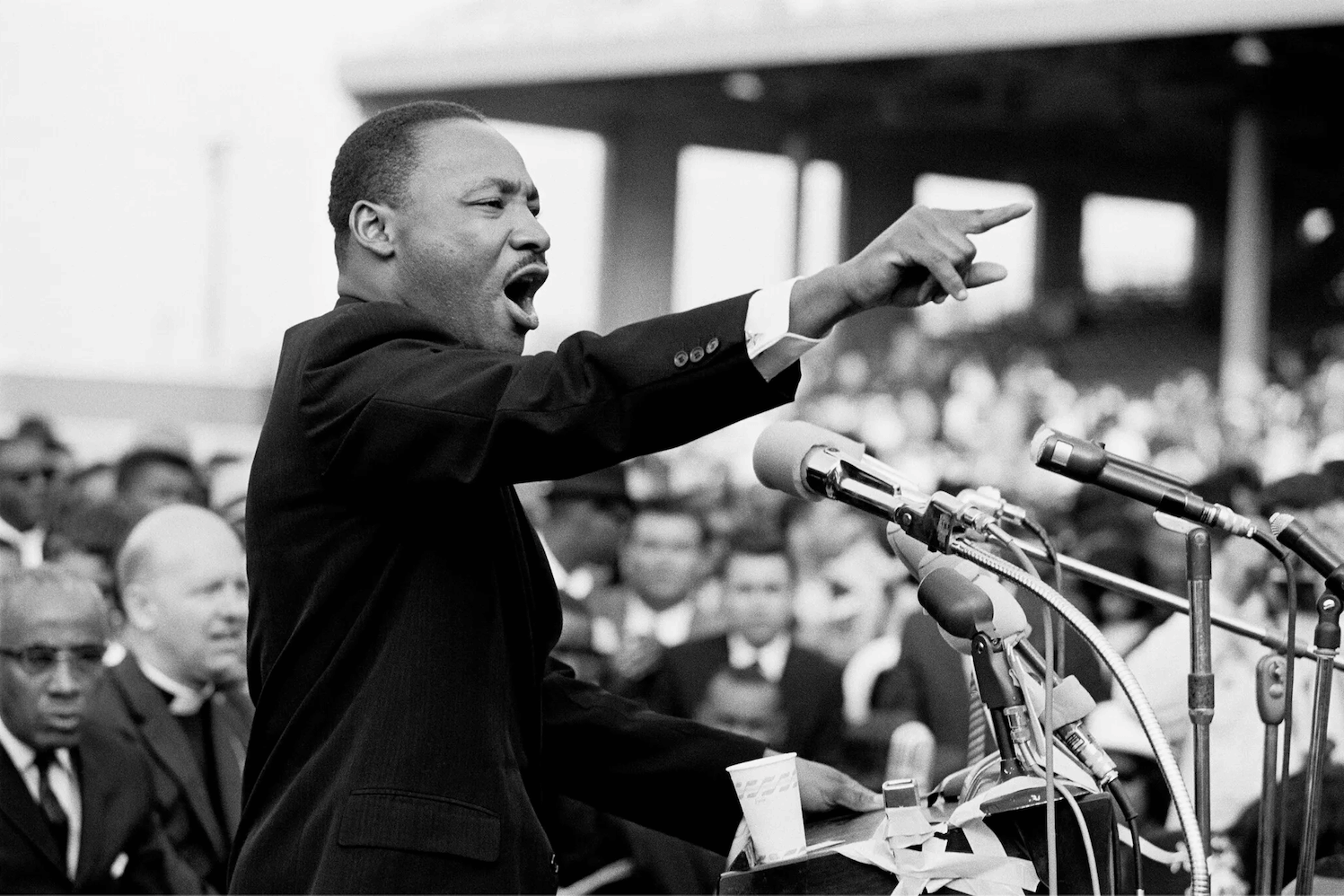

When the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at a civil rights rally in Los Angeles in 1963, Mr. Wasser was there. When the Watts neighborhood erupted in riots in 1965 after a Black man there was brutalized by the police, Mr. Wasser captured the agony of a city at war with itself.

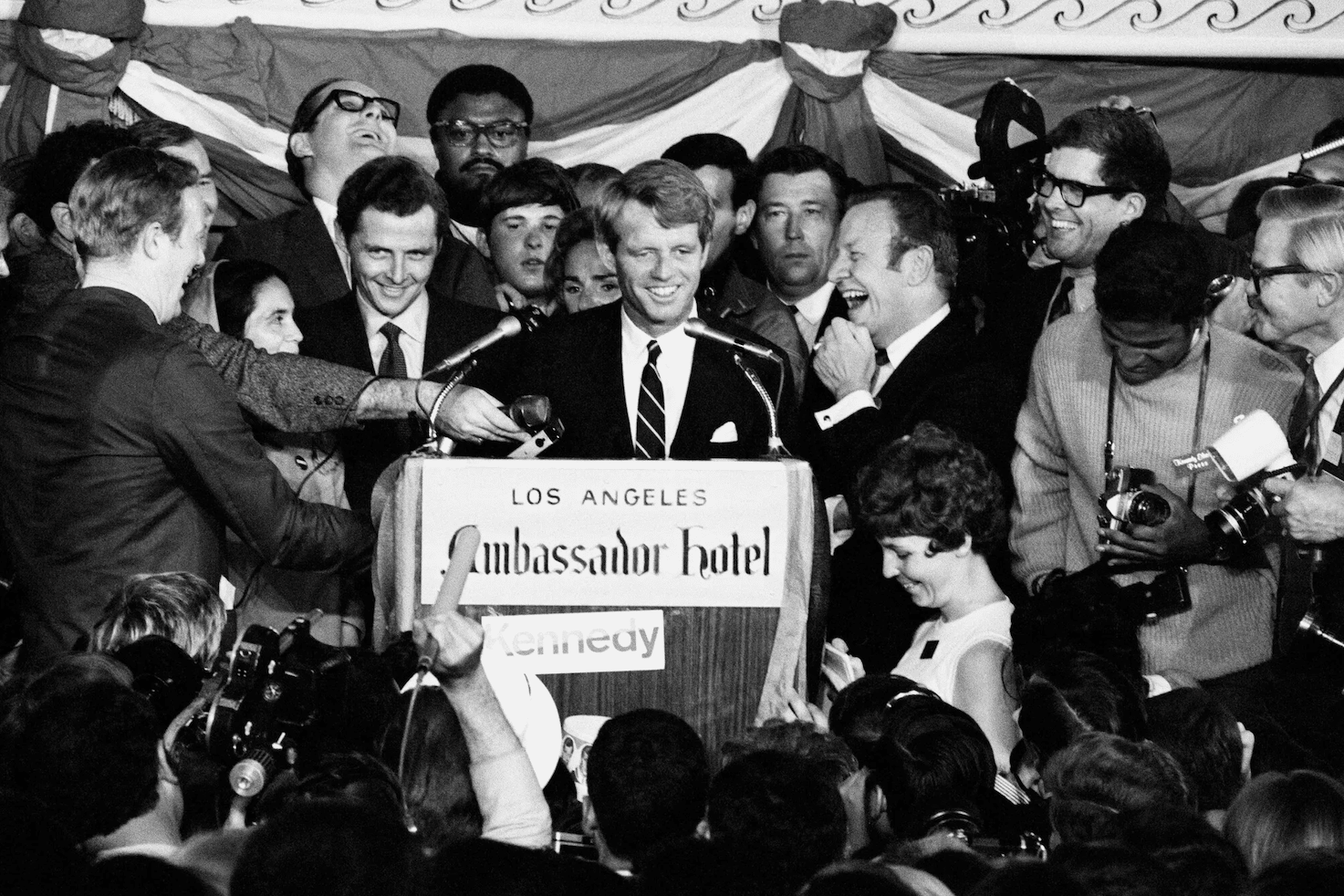

And when Robert F. Kennedy addressed his supporters at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles in 1968, after winning presidential primaries in California and South Dakota, Mr. Wasser photographed the joyful young senator, just moments before his assassination.

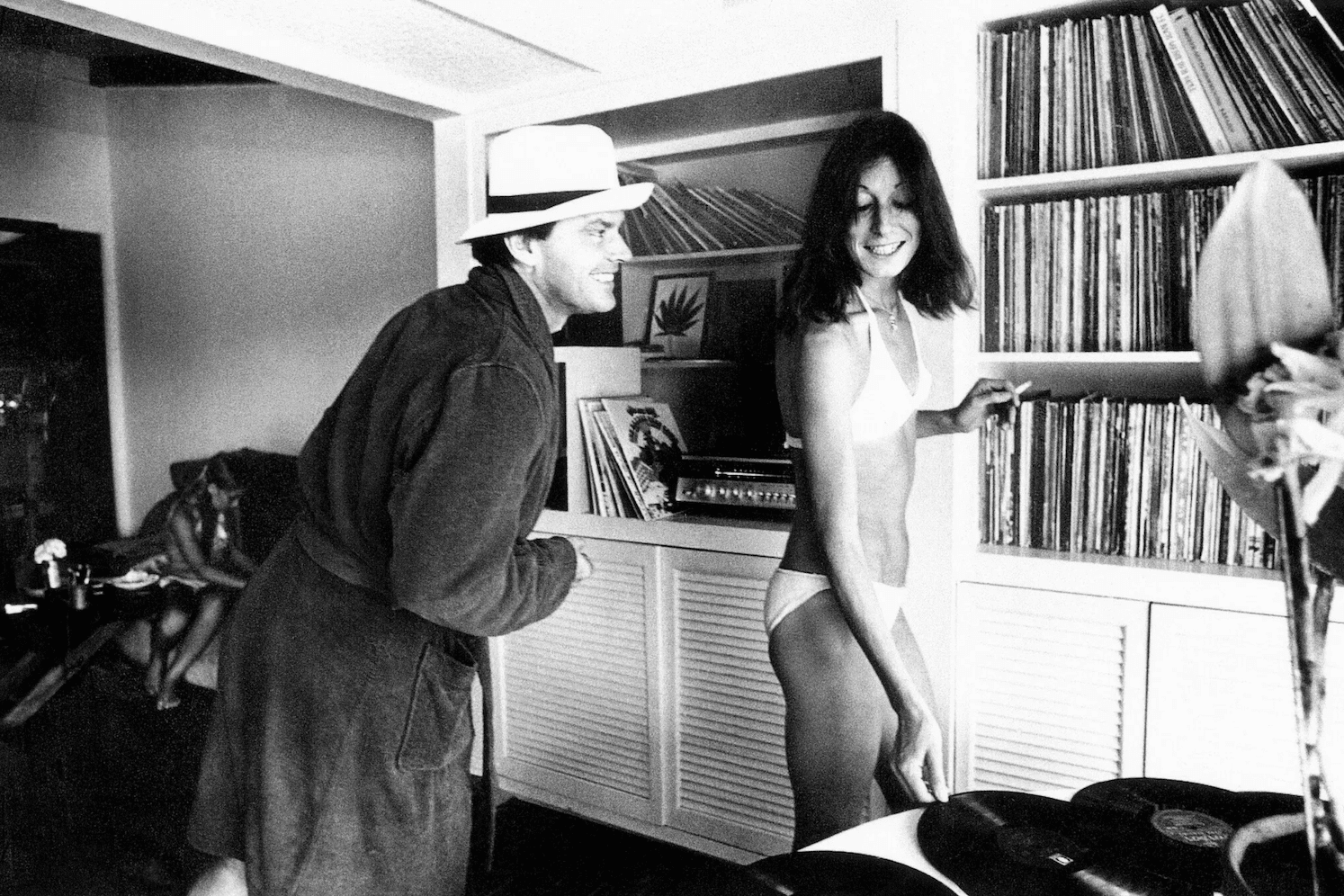

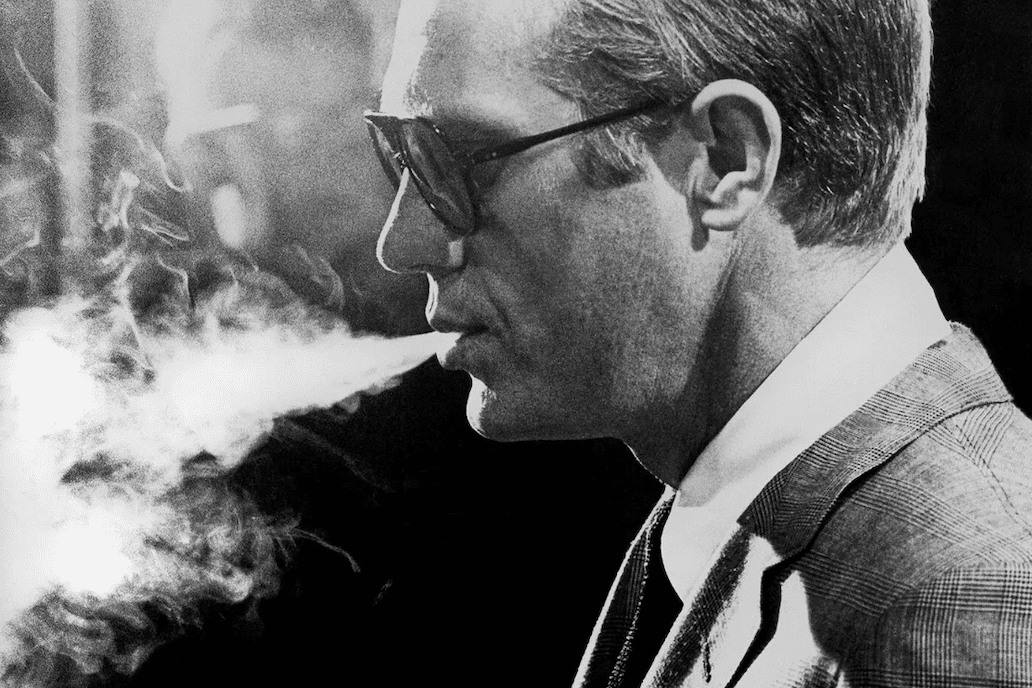

Yet Mr. Wasser was perhaps better known for chronicling L.A.’s counterculture and its outsize bohemian characters: He shot a bikini-clad Anjelica Huston and Jack Nicholson horsing around in a living room; Steve McQueen on a movie set, exhaling a plume of smoke and exuding a glacial cool; and countless scenes from the Whiskey a Go Go, the hot nightclub on Sunset Boulevard.

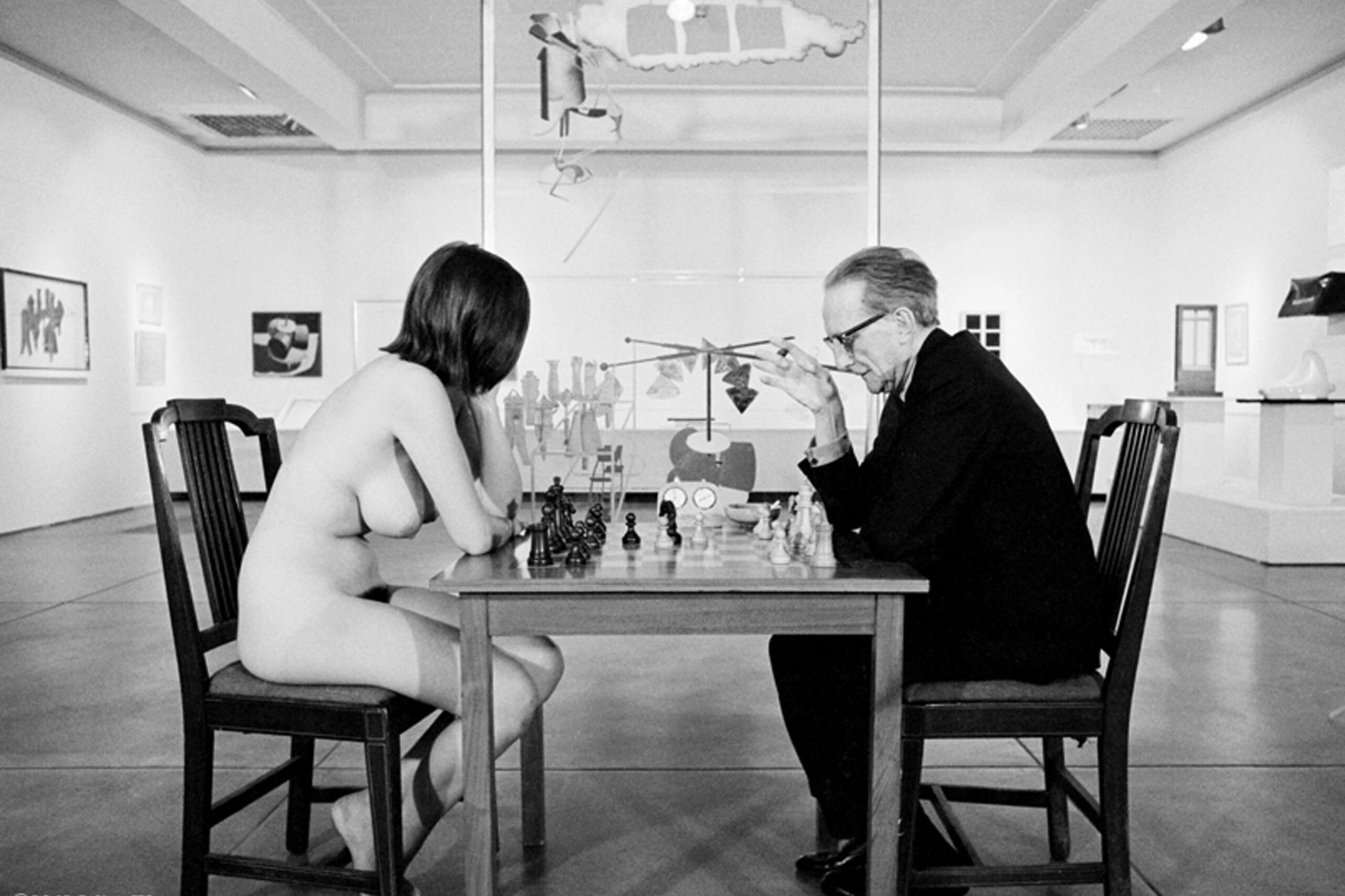

Mr. Wasser was also the perpetrator of “that photo” of Eve Babitz, the late author and sensualist, then age 20, naked and playing chess with the artist Marcel Duchamp, a stunt hatched during the artist’s retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1963. The museum’s director, Walter Hopps, happened to be Ms. Babitz’s (married) boyfriend.

Stories, and memories, have varied over the years, but as Ms. Babitz told it, the photograph was an attempt to annoy Mr. Hopps, who took his wife instead of Ms. Babitz to the exhibition’s opening.

Mr. Wasser said that the composition was his idea. “I had always wanted to see Eve naked,” he said in an interview with The New York Times for her obituary in 2021, “and I knew it would blow Marcel’s mind.”

The black-and-white image became so famous it showed up in a poster for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The art critic Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp’s biographer, called it “an erotic and very Californian footnote to Walter Hopps’s historic show.”

James Danziger, one of Mr. Wasser’s gallerists, said Mr. Wasser had “brought an artist’s eye” to his photojournalism.

“You could call it the auteur theory of photography,” Mr. Danziger said. “You let things happen, but if it made for a better picture, you weren’t afraid to direct the scene.”

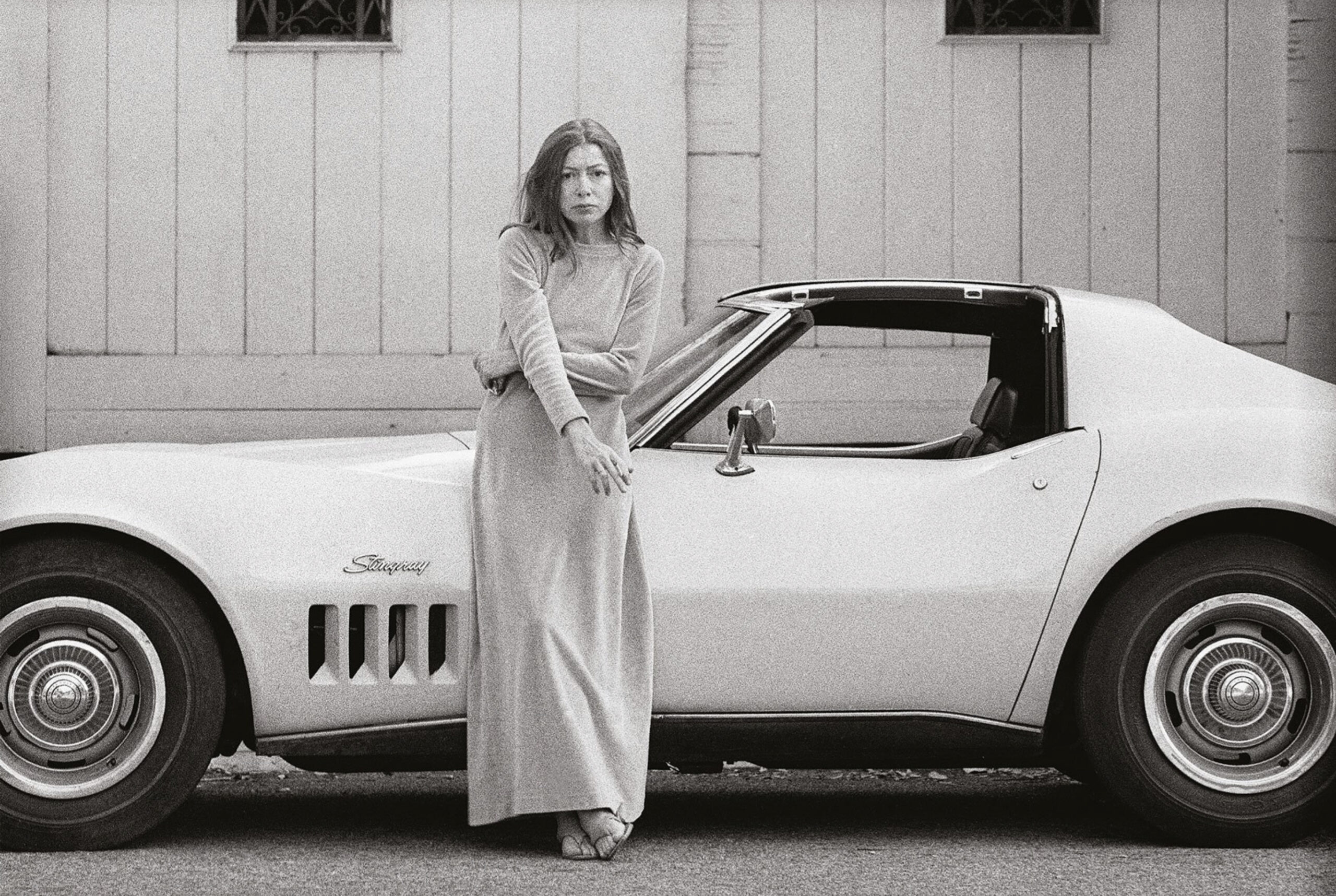

And then there were the photographs of Joan Didion, commissioned by Time Inc. in 1968, shortly after her essay collection “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” appeared. There is Ms. Didion, steady eyed and brandishing a cigarette, in a variety of poses with her Corvette Stingray, potent images now etched into the collective consciousness.

The pictures appeared on Ms. Didion’s books, were recreated by the fashion company Celine in a homage to the author featuring the model Daria Werbowy, and were the subject of a 2015 show at Mr. Danziger’s gallery in Manhattan. They could even be spotted on tote bags, as Ms. Didion’s nephew Griffin Dunne did on the subway on his way to her memorial, sported by young women who were also en route to the service, Didion groupies with literary swag.

When Mr. Dunne interviewed Mr. Wasser for his 2017 documentary, “Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold,” Mr. Wasser recalled how he had shot only two rolls of film that day.

“He knew he got it right away,” Mr. Dunne said. What he did not anticipate, he added, was how people would react to the photos. “He never dreamed they would be on tote bags, as iconic as a Che Guevara T-shirt,” he said.

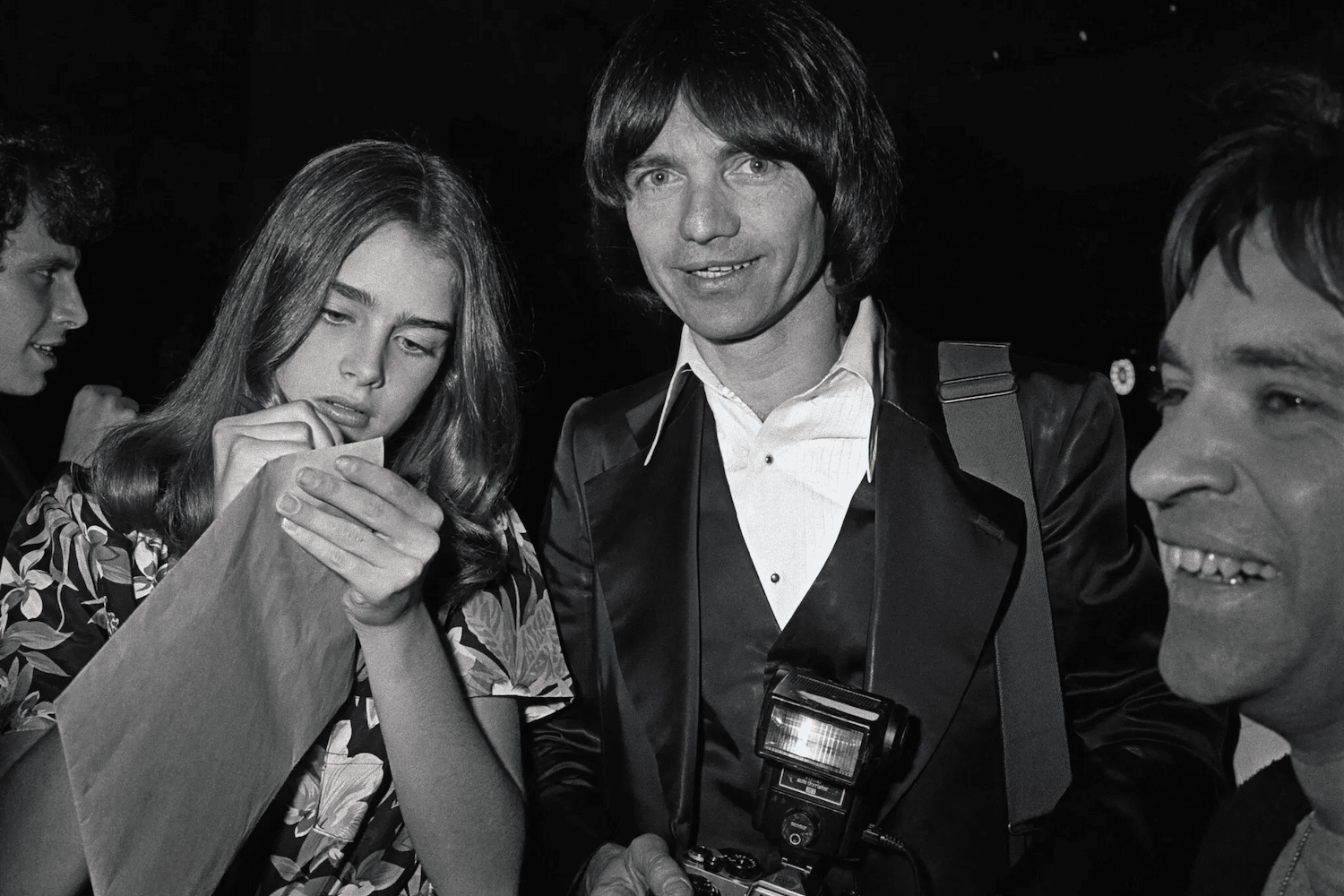

With his shaggy hair, leather jacket and holster of beepers and police scanners, an assortment of cameras and press badges slung around his neck, Mr. Wasser was quite a presence himself, said Craig Krull, a gallerist who represented him for the last 30 years. “He had an unflinching eye for the intensity of experience in L.A.,” Mr. Krull said, “whether it’s a club on Sunset Strip or the Manson murders or the Watts riots.”

Mark Rozzo, whose 2022 book, “Everybody Thought We Were Crazy: Dennis Hopper, Brooke Hayward and 1960s Los Angeles,” covers much of the territory that Mr. Wasser did and used one of his photos — of Ms. Hayward and Mr. Hopper looking especially mod and particularly glum — said that Mr. Wasser was “perhaps the closest thing that Los Angeles has had to a photographer laureate.”

At least for his rollicking moment. “This was the period of Didion writing in The Saturday Evening Post and Ed Ruscha’s street-inspired pop art and Brian Wilson’s teenage symphonies to God,” Mr. Rozzo said. “Julian was right in the center of it all, and he made sure he was at the center.”

Julian Wolf Wasser was born on April 26, 1933, in Bryn Mawr, Pa., the only child of Leo and Frances (Rothman) Wasser. His father was a lawyer, his mother a schoolteacher. He grew up in the Bronx and Washington, D.C.

A teenage news junkie, Julian cut school and sneaked out of his room at night in imitation of his hero, Arthur Fellig, the photographer better known as Weegee, to chase down crime scenes with a police scanner and submit the photographs to newspapers, which inevitably published them.

“Every night I would climb out my bedroom window and steal my father’s car when I was 12 and take pictures, and they’d be on the front page of The Washington Post,” Mr. Wasser told a television reporter in 2019. “My father would say, ‘Look, there’s another Julian Wasser in Washington.’ I said, ‘Yeah, Dad.’”

He worked as a copy boy for The Associated Press in Washington and, by his account, was able to meet Weegee and accompany him to crime scenes when the photographer visited Washington.

His daughter said that as a child she was often deputized as her father’s assistant. She monitored his ever-crackling police scanner: “Daddy, the night stalker is being arrested!” (She was 4 years old at the time.)

When Will Smith married Sheree Zampino, his first wife, the Wassers crashed the wedding. Alexi Wasser, then 11, was armed with a disposable camera, which she was savvy enough to stash under her shirt when security arrived to remove the unauthorized photo team. She recalled her father saying with a straight face, “I’ve never seen that kid before.”

“It was all very absurd and ridiculous,” she said. “Later Julian told me my photographs ran in whatever tabloid he was shooting for, but he stole my credit line. Our relationship had a very Ryan and Tatum O’Neal ‘Paper Moon’-esque quality.”

In addition to his daughter, Mr. Wasser is survived by a son, James.

In 2014, Mr. Wasser published a photographic memoir, “The Way We Were,” more than 170 pages of his greatest hits, and then some.

“The effect of so many otherworldly behind-the-scenes pictures plays out like a kind of movie in itself,” Rebecca Bengal wrote in the New York Times magazine T. “As Wasser captures them, in grainy close-ups and candids, the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s marked a time of unusual access: carefree, hair-let-down moments and stars mingling with real people.”

“It wasn’t like it is now,” Mr. Wasser told The Guardian in 2014. “There were no paparazzi, no VIP sections, no security. It was a really innocent time. You’d just walk up and there they were. They’d stop and smile and pose.

“Now it’s a business,” he continued. “If you want exclusive access to a celebrity, you have to pay big money. You weren’t considered some sort of psychotic menace who’s going to rob or kill them either. Now they’ll call their security person and you’ll get beat up.”

A correction was made on Feb. 15, 2023: An earlier version of a picture caption with this obituary misstated when the photo of Jack Nicholson and Anjelica Huston was taken. It was 1974, not 1971.

Julian Wasser, Famed L.A. Photojournalist, Dies at 89

admin

Wasser’s iconic photographs of the 1960s and 1970s L.A. demimonde captured the city and its popular culture at a moment of reinvention.

Photographer Julian Wasser, who captured multiple shades of light and dark during the cultural upheaval in Los Angeles during the 1960s and 70s, died on Wednesday night. He was 89.

As a teenager, Wasser began photographing crime scenes in Washington, DC, borrowing his father’s Contax 35mm camera. His striking skills in composition led to his recruitment as a West Coast contract photographer for Time magazine, among other major publications of the era. Along the way, he captured iconic images of Steve McQueen, the Fondas, Hugh Hefner, Joan Didion posing with her Corvette Stingray, and a closeup of a still-glowing Marilyn Monroe applauding at the Golden Globes in 1962.

In 1963, assigned by Time to cover the landmark Marcel Duchamp exhibition at the Pasadena Art Museum, Wasser shot the conceptual artist playing chess with a nude woman. As Duchamp’s naked opponent, Wasser recruited 19-year-old Eve Babitz, later an acclaimed L.A. writer, who happened to be dating the married curator of the show, Walter Hopps.

“Well, [Duchamp] was into chess and he did the Nude Descending a Staircase. So you get a nude, chess, a girl with giant tits. Why not?” Wasser told Los Angeles last year as part of an exclusive oral history of Babitz. “I photographed Eve before. She was a total exhibitionist, so anything could happen.”

The image became one of Wasser’s most famous photos, but it was just one of many assignments over the decades that captured moments of high pop culture with style and skill at a highly competitive time in photojournalism. The 60s in particular was a special time in Los Angeles, long before TMZ and an army of paparazzo commandos descended. Celebrities were more accessible then, Wasser recalled, and the pictures were better because of it.

He was as comfortable on movie sets with Jack Nicholson and Alfred Hitchcock as he was visiting Rodney’s English Disco on Sunset Blvd. for a fiery performance by Iggy and the Stooges. He captured now-classic portraits on sound stages for Charlie’s Angels to Rosemary’s Baby and mingled easily with the pop stars of the moment: the Beatles, Beach Boys and Byrds in the 1960s; Bowie, the Jackson 5 and the New York Dolls in the 1970s.

For years, Wasser worked out of a pair of apartments (across the hall from Leslie Caron) on Young Drive in Beverly Hills, surrounded by police scanners to alert him to scoops, and owned one of the first mobile phones in Los Angeles.

“He was one of the most unique individuals I ever met: brilliant, funny, charming, charismatic, educated, self-taught,” says photographer Brad Elterman, who met Wasser in 1976.

“My father lived life on his own terms. He was a very interesting, talented, funny, character. I’m very grateful to be his daughter,” artist-actress Alexi Wasser posted of his death on Instagram. “Whether in L.A., New York, Paris, Berlin, or London, he lived to hang out! He loved meeting people, making wisecracks, flirting, being inappropriate, taking photos, watching movies.”

In 2014, Didion told Vogue that Wasser’s photograph of her with baby daughter Quintana Roo in 1968 was “my favorite picture ever. Julian took beautiful pictures. Anybody who had their picture taken by Julian felt blessed.”

Wasser is survived by his daughter, Alexi, and son, James.

The Final Step: Turning My Photos Into Prints for Galleries Around the World

BY: MARKUS KLINKO

JAN 05, 2023

admin

Une trentaine d'œuvres, à la fois physiques et digitales, du photographe américain sont exposées dans la boutique Versace de Bruxelles.

Creating a successful photograph is a process that has numerous stages. Printing the work masterfully, usually the last portion of the endeavor, is paramount.

As I enter my 29th year as a documentarian of pop culture (often referred to as fashion/celebrity photographer), I have seen my work move from the covers of magazines onto the walls of art galleries, museums, and private art collections.

Now getting ready for new shows in Houston, Texas, and Ventura, California, it is time to talk about the all-important aspect of printing.

After all, the print is what everyone sees, and what the photograph will be judged by. So why not pay a little tribute to the people that make this all happen?

There are many ways to make a gorgeous print, and choosing the ideal paper is critical. For my work, I prefer a glossy luster, so Fujicolor Crystal Archive Digital Pearl is my paper of choice.

It has a distinct metallic reflection effect that suits my work to perfection. I also love Fujiflex Crystal Archive Printing Material, for its razor-sharp rendering, vibrant colors, and impeccable whites.

I do not print my own work — after many trials and errors, I have had the fortune of collaborating exclusively with the great master printer, John Weldon of LA’s famous Weldon Color Lab. After working with John for many years on dozens of solo exhibitions, group shows, and art fairs, I recently sat down with John for a bit of a recap of his career, and to hear how he applies his talent and great experience to my work.

I asked John about his journey to becoming one of the world’s premier printmakers and how it all started.

“My freshman year in high school I found an old telescope in the closet and my dad, an engineer on the first Apollo missions, told me I’d be able to see the craters on the moon,” John says. “It was so amazing that I put my camera up to the eyepiece and when I got the film back from the drugstore it came back with a note on it: no charge – no images. So I shot it again and put a note on it that the photos were of stars and planets, and the white dots on the film were the actual photos. The roll came back with another note: no charge – no images.

“My dad saw this and for Christmas gave me an old darkroom set-up so that I could process the photos myself. Next thing you know I started processing color prints in the darkroom I’d built in my bathroom! When I showed some neighbors my photos pretty soon they started bringing me their negatives to print.

“While still in high school by chance I discovered a black and white rental darkroom in the neighborhood, and soon they offered to pay me to do color printing for them. Ten years later, in 1989, my fascination with photography inspired me to open my own photo lab at our current location where I began specializing in Cibachrome printing. As the technology has continued to evolve, so too has the lab continued to grow. We are currently one of the only labs in the world with top expertise in Lightjet printing.”

John says the challenge of helping photographers achieve their vision is the “secret ingredient” behind what allowed his lab to develop its reputation as one of the premier printing companies in North America.

The lab has grown to offer a very wide range of services for photographers.

“We do it all at Weldon – from film development to scanning to printing and mounting!” John says. “Our state-of-the-art Lightjet printing offers an amazing level of vibrancy. And our archival inkjet prints allow for a complete range of unique papers and surfaces to choose from to complement any type of photograph. We develop film in our custom black-and-white film-processing lab with great care by hand, utilizing traditional archival development.

“Our scanning department offers a range of services, including high-resolution drum scanning, and flatbed scanning, and our digital photography can accommodate reproduction of large-scale paintings.”

I asked John whether most of his clients have specific requests regarding the printing process and the paper used, or whether he helps to direct artists to their eventual choices.

“While we do assist clients new to photography every week select the best options for their images, the majority of our clients are professional photographers, museums, and galleries,” John says. “Professionals usually know what kind of style they want, but are always happy to hear about the latest innovations.”

Weldon Color Lab recently introduced the historic art of platinum palladium printing, which inspired me to release my David Bowie Platinum Edition — a platinum print I have included in my STARMAN show.

“Platinum-palladium prints are unrivaled by any modern printing technique, both in appearance and performance,” John says. “One reason the prints, created on Hahnemuhle paper, are favored by art collectors is due to their longevity, achieving an archival rating in excess of 1,500 years. And in terms of appearance, the prints create an added sense of depth, and the tonal range of the prints is unmatched.

“Dating back to the 1870s, this handmade photographic-printmaking technique was created through contact printing, meaning the photographic negative matches the size of the final print. As a result, photographers of the times were more limited to what size they could make their prints. Now we can make ‘digital negatives’ up to 40″ wide! Currently, we are printing up to 24×30″ and are excited that later this year will be able to print 30×40″ platinum-palladium prints.”

John says his lab is currently looking to expand its platinum services to serve galleries and museums around the world.

About the author: Markus Klinko is an international fashion/celebrity photographer who has worked with many of today’s most iconic stars of film, music, and fashion. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can find more of Klinko’s work on his website and Instagram.

Joan Didion Remembers the Day Julian Wasser Took Her Portrait

admin

Vogue spoke with Joan Didion and Julian Wasser about his portraits of her, now in Wasser’s new monograph, The Way We Were.

BY ABBY AGUIRRE

Shortly after Slouching Towards Bethlehem was published, in 1968, Timemagazine commissioned portraits of Joan Didion by the photographer Julian Wasser. You know the series: a young Didion in a long-sleeved dress and sandals, standing in front of her Corvette Stingray, a cigarette dangling from her right hand. Two of these portraits appear in Wasser’s new monograph, The Way We Were, published recently by Damiani, alongside many of his other seminal photographs: Steve McQueen exhaling a cloud of cigarette smoke; Robert F. Kennedy five minutes before he was shot; Roman Polanski kneeling near the entrance of the house on Cielo Drive, the word PIG,scrawled in blood by the Manson family, faded but still visible on the door.

Of all the pictures he took during those years, Wasser says, speaking by phone from Los Angeles, the ones of Didion were “a big event in my life.” “I’d read her fiction,” he says. “It was very L.A. She didn’t miss a thing. She was such a heavyweight person.” Wasser shot Didion on the Strip and at her rented house on Franklin Avenue in Hollywood, where she lived with her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne, and their daughter, Quintana Roo. “It was a very nice, cozy house,” Wasser remembers. “And she was a very easy person to talk to. It was like a dream. Quite nice and relaxed. No Hollywood phoniness.” Vogue asked Didion, too, for her memories of the shoot.

These portraits were commissioned by Time in 1968, just after Slouching Towards Bethlehem was published to great acclaim. What do you remember about this moment in your life?

I think someone said that the picture had been taken under circumstances that it hadn’t. What do I remember? I can’t say what I remember. I had a baby. I was living in a rented house in Hollywood. It was kind of a wonderful period of my life actually. Not because I was in a rented house in Hollywood. But just in general.

As a writer and reporter, was it strange for you to be the subject of a story? To be appearing in Time?

I don’t think it was the first time I’d been written about. The whole thing was strange. Yes, it was strange to be written about. But that probably wasn’t the first time. I loved having pictures of me with the baby. The one where she has sort of—the one that shows her hair pulled up tight? I love that picture. I love that picture. That was also at Franklin Avenue. Most of what Julian Wasser took was at Franklin Avenue.

Was this the first time you met Julian Wasser? Were you familiar with his work?

I was very familiar with his work because I was writing for magazines then and he was at the Time bureau. Any time anyone was shooting in L.A. for Time and Life, they were shooting with Julian. He was just somebody I knew very well.

What details do you remember about that day? Does anything in particular stand out to you now?

I can’t remember anything specific that stands out about the day. I don’t know how we decided to include the Corvette. It must have been some whim of Julian’s.

He said it was not his whim. He said, “You don’t tell a woman like that what to do.”

[Laughs] Oh, really?

Had you thought about what you were going to wear, or were the long dress and sandals just what you happened to have on?

I remember the long dress. I remember being out on the Strip in a long dress. Why, I can’t imagine.

Do you remember buying the Stingray?

I very definitely remember buying the Stingray because it was a crazy thing to do. I bought it in Hollywood.

What color was the Stingray?

The Stingray was Daytona yellow. Which was a yellow so bright, you could never mistake it for anything other than Daytona yellow.

Did you like these photographs of you?

The picture with the baby—I would say that was my favorite picture ever. Julian took beautiful pictures. Anybody who had their picture taken by Julian felt blessed.

How did you feel about the article?

I don’t remember the article. I remember the pictures.