At the Field Museum, visions of Dante

Kerry Reid

JUNE 19, 2013 | MARCO NEREO ROTELL

Dante Alighieri’s “Divine Comedy” stands as the greatest achievement in Italian literature and one of the most influential epic poems ever written. Even Don Draper could be found reading it while sunning himself on a Hawaiian beach in the season opener of “Mad Men.”

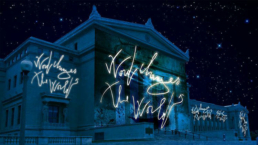

So it is not surprising that it would serve as the inspiration for internationally celebrated Italian artist Marco Nereo Rotelli’s “Divina Natura.” On Monday, for one hour only, Rotelli’s collaborative installation of light, projected images, music and live poetry will turn the north and west facades of the Field Museum into a living architectural manuscript meditating on Dante’s visions of heaven and hell, nature and numerology, reality and representation.

Rotelli notes that Robert Pinsky, former U.S. poet laureate and translator of Dante’s “The Inferno” from “Divine Comedy,” had sparked some ideas about the Italian master’s work in a short poem he gave Rotelli during an earlier collaboration. “ABC” begins with the line “Anybody can die, evidently. Few go happily, irradiating joy, love, knowledge.”

So, says Rotelli, when he was approached by Silvio Marchetti, the director of Istituto Italiano di Cultura about creating a site-specific installation for Chicago’s celebration of 2013 as the Year of Italian Culture in the United States, “I wanted to take a poem of the Italian culture that became an object of all the world.” He also wanted, as he had done in many of his works, to bring in global visions of poets. In doing so, he reached out to past collaborator Arica Hilton, an artist, poet and owner of Hilton Asmus Contemporary gallery in River North and former president of the Poetry Center, to help him find poets who could work with cantos that Rotelli selected from Dante and give them a contemporary spin.

What they ended up with is poets mostly based in Chicago, but with roots in other countries and cultures.

“What we had talked about was trying to bring to light different cultures and how they can interact,” says Hilton. The poets will read bilingual versions of their work.

Syrian-born poet Osama Esber’s “In the Land of Revelation” meditates upon the civil war ravaging his native land — “in a country where Divine Revelations chose to visit in bullets and blades.” He will read in English and Arabic.

Hilton’s “Bring in the Fruit (Epuisse),” inspired by Canto 33 in which a prisoner starves to death in a tower, came about when “I realized it was about ego and greed and domination, and that this is what is going on in the world today in politics.” But, her poem promises, “There is a way to swim out of the ninth circle of hell, I tell you. There is a way.” Hilton will read part of her poem in Turkish — also timely, given the current protests in Istanbul.

But “Divina Natura” isn’t meant to be a depressing litany of the hell-on-earth created by human cruelty and indifference. Using richly saturated reds and blues, Rotelli will turn the Field into a canvas upon which an array of Dantean creatures (the leopard, the lion and the wolf) and numbers (the poet’s use of numerology has inspired scholars for centuries) can break away from the printed page and engage with one of Chicago’s most-loved buildings, and in the process celebrate both nature and the better angels of human nature.

“For me, the space where I work is a concept,” says Rotelli, who first trained as an architect. “It is interesting for me to work on horizontal architecture in a city of the vertical.” Long fascinated with lost languages, Rotelli also finds inspiration in the Field as a repository of natural history and cultures, as well as in its location near the lake, with its vista of the horizon of water and sky.

“The light, the poetry, the architecture all suggest the possibility of joining the past and the present,” says Rotelli. And as Marchetti notes, the Field’s location on a hill overlooking major thoroughfares allows for the installation to be glimpsed by those passing by.

In addition to the poetry (other participating poets include Elise Paschen, Ana Castillo, Giuseppe Conte, Reginald Gibbons, Lia Siamou, Thomas Haskell Simpson and Chana Zelig), “Divina Natura” also incorporates an original soundtrack featuring original compositions by Adrian Leverkuhn and Thomas Masters as well as soprano Karolina Dvorakova.

For a city known as “Nature’s Metropolis” — as William Cronon dubbed Chicago in his signature history — as well as one that romanticizes its own phoenix-from-the-ashes past, there may be a special resonance in Rotelli’s “Divina Natura.” But for all who look wearily upon the never-ending bad news in the headlines, Rotelli promises that the installation can remind us that “The mind of every man, every poet, is looking toward heaven.”